Our May 2015 Perfect Health Retreat has just concluded. It was a rousing success: we had a great time, the program was better than ever, and we appear to have had excellent health outcomes.

But, thanks to a busy winter, I have barely begun to blog about the October 2014 retreat. I have many testimonials to share from October. One of them came from a celebrity guest: low-carb podcaster and author Jimmy Moore.

Why I invited Jimmy to the Retreat

Jimmy and I first met in person at the first PaleoFX (in 2011). There we had a long conversation about starches, and I encouraged him to try them. He seemed open to the idea and we agreed that he would do a “PHD” trial at some future time.

The years passed and we never did the trial, but at AHS 2014 we continued our conversation. Jimmy was more committed to a low-carb (now ketogenic) approach than ever, and I was more persuaded than ever (in part due to my friend Seth Roberts’ death; I’ll blog about that soon) that such a diet risked an early death from cardiovascular disease. I again encouraged Jimmy to try PHD and see if he felt better on it. Jimmy said that he didn’t feel he could give PHD a fair test on his own, because he didn’t fully understand it.

If you meet a man dying of thirst, you have an obligation to lead him to water; even if he has an irrational aversion to water, and you know he is unlikely to drink. Still, if you refuse to show him the water, you share the guilt for his suffering. If you show him the water and he refuses to drink, his suffering is his fault alone. In the same way, I felt an obligation to show Jimmy the way to a healthier diet, even if I knew it was unlikely he would drink from that pool. We weren’t quite sold out, so I invited Jimmy to do the PHD experiment for one week at our retreat. Jimmy and his wife Christine accepted the invitation.

Jimmy’s Praise of the Retreat

On the final day of the retreat, Jimmy generously recorded a video testimonial for us. After seeing the final edited video in January, Jimmy signed an authorization for us to use it. Here is the video:

For those who don’t like to watch videos, here are some quotes:

- “We had such a great time”

- “It was such an amazing time”

- “The camaraderie among the attendees was better than I have seen with any other group”

- “I enjoyed the food better than anything … It surprised me that it was not only tasty, delicious, and nourishing which I expected it all to be but I wasn’t quite as hungry as I thought I’d be eating more carbohydrates than I’m used to.”

- “This setting is absolutely spectacular.”

- “I’ve considered myself a pretty good exerciser … but you challenged me…. I learned quite a bit.”

- “I was very pleased [with the science classes]…. I really hope you pack this place out … The circadian rhythm stuff dude that is the best stuff you’ve done … that has helped my sleep and helped me get back on track with that more than anything.”

- “I actually was surprised [by how beneficial the health coaching was] … You provided information that no doctor ever has.”

- “This would shock a lot of people but I would absolutely recommend the retreat because I think if you’re interested in your health, you deserve to know all the evidence…. I think you owe it to yourself to give PHD a chance, learn about it, see if it works for you, and give it a go.”

- “Very glad I did it, and highly, highly recommend it for anyone else”

For those who are wondering, there was no quid pro quo between us. Jimmy had no obligation to give us a testimonial, and I’m grateful for his enthusiastic endorsement of the retreat.

Jimmy’s Recent Blog Post

Although they enjoyed their week at the retreat, it didn’t change their minds about their own diets. Jimmy and Christine told me when they left the retreat that it was clear PHD was bringing health benefits to many people, but they themselves, and many of their readers, were different and needed a lower-carb diet to be healthy.

Their conviction that eating moderate levels of carbs would harm their health came out in a blog post Jimmy published on May 2, the first day of our May 2015 retreat. “Paul Jaminet’s Perfect Health Retreat: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly” is a discussion of “my thoughts of the good, the bad, and the ugly about what this event was like for us.”

The important words here are “for us.” Those who only read headlines might obtain the impression that the retreat itself was “bad” or “ugly”; but in fact most of what Jimmy refers to as “bad” and “ugly” are statements about the biological reactions he and his wife had to eating carbs.

Although Jimmy may not have intended to denigrate the value the retreat brings to those who actually want to eat carbs, I feel that casual readers will interpret his post as a denigration of the retreat, so I’d like to correct the record. Also, I disagree with his interpretations of his experiences, and I think my commentary on the science may be helpful to many – even Jimmy, if he is open to it. So I’d like to respond in detail.

The “good” in his post repeated statements from his video testimonial above; so I’ll discuss only the “bad” and “ugly.”

The Bad #1 – Disorganized Schedule

This was his sole criticism of the retreat itself. Jimmy wrote:

There was a general schedule of waking up, attending a morning seminar, morning workout time, doing a kitchen class, eating lunch, afternoon free time, afternoon workout time, afternoon cooking class, evening meal, meditation class, and then sleep. But it would have been nice to have some semblance of a written schedule to at least know what we’re doing next…. This is easily resolved with a schedule.

We did in fact have a schedule, it was emailed to guests as part of a larger information packet in advance of the retreat and written on a whiteboard in our dining area. Jimmy himself took a picture of the whiteboard (from his Instagram):

In future retreats, the welcome kits that guests receive when they arrive will include a printed handout of the schedule, a map to help them find class locations, and a detailed description of the topic of each class, so that those who prefer to skip a class in favor of hot tub, pool, ocean, beach, or Internet browsing may know what they are missing.

For May this year, we revised the schedule, moving the start of science classes back from 9 am to 8:30 am and giving more time to movement and cooking classes. This helped prevent slippage of start and end times, something we experienced in October 2014.

It takes some experience to make everything move like clockwork. We’re getting there.

Overall, I think our organization deserves a great deal of credit. We delivered an ambitious program successfully. Our staff of 11 in October 2014, 13 in May 2015, was well coordinated. Many guests complimented us on what we had achieved. One October 2014 guest, CEO of a $100 million per year company who frequently stays in 5-star hotels, told us that he was very surprised by how well we had managed to deliver luxury hospitality rivaling the best he had experienced. (Credit where credit is due: We benefited from having David Spence, the principal of a luxury hospitality business, come as our guest to the May 2014 retreat and provide us with detailed advice on how to improve our hospitality. Susan Savery of Savery Services has been outstanding as our concierge.)

The Bad #2a – Christine was hungry

Jimmy writes:

[A]lthough we were told to eat at least two pounds of food per meal and as much as we wanted to satiety, Christine was constantly hungry throughout the retreat.

Although this experience is uncommon, it’s quite possible for this to occur.

A full plate of PHD food in PHD proportions weighs about 2 pounds and has about 900 calories. We serve two meals per day so “two pounds” per meal works out, including a glass of wine, to about 1900 calories per day. However, calorie needs vary based on body size, age, activity levels, and health considerations, so we don’t provide calorie or food weight guidance. Rather, our guidance is, “Eat as much as you want in the first days of the retreat. Then, as you get experience with intermittent fasting, calibrate your food intake during the feeding window so that you just begin to experience mild hunger at the end of the next day’s fast. ‘Mild hunger’ means that you notice it if your attention is unoccupied, but forget it if you give your attention to something else, such as exercise, an interesting conversation, or interesting work.”

For most guests, PHD food is highly satisfying from the first day of the retreat, and there is little to no hunger during the fast. For most others, there may be hunger during the fast for a few days, but by the end of the week, they feel satiated and begin eating less and having no hunger during the fast.

However, occasionally someone may remain hungry for a full week. Invariably this is someone who has been undereating either total calories or carbs before coming to the retreat. So far we have only seen this occur in women.

We had one such person in May, out of 27 guests. I would say that this phenomenon of week-long hunger affects no more than 3% of the people who come to our retreat.

Why does this happen? As we discuss in our book (Chapter 17), nutrient deficiencies drive appetite. A dearth of a key nutrient, such as carbohydrates, will drive appetite.

The exception to this is that, if a missing nutrient is chronically unavailable, hunger disappears. The brain does not want hunger to distract us from critical activity – the search for food. Thus, starvation itself is anorectic – it tamps down hunger.

However, once the starving person finds the food or nutrient she needs, the hunger returns, amplified. The brain acts as if the starving person, after a long trek through the desert, has found an oasis that may be only transiently available. Therefore, it makes the person ravenously hungry, to get her to eat as much as possible while food (or the missing nutrient) is available.

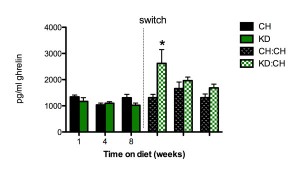

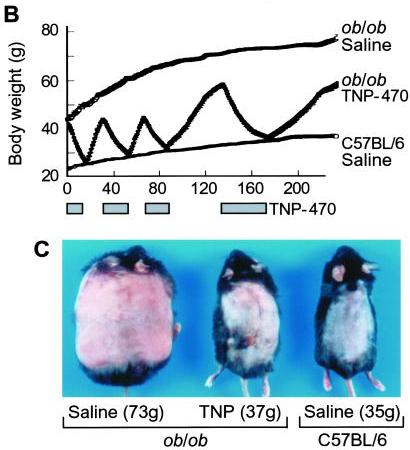

Ketogenic diets are generally carb-starved diets, and carbs are a critically important nutrient; so it is not surprising that ketogenic diets lead to exactly this pattern. Here is an animal study which measured hunger through serum levels of ghrelin, the “Hunger Hormone.” [1]

Rats were put on a ketogenic diet (KD) or chow diet (CH) for 8 weeks, then the ketogenic diet rats were switched to a chow diet. The ketogenic diet suppressed ghrelin a bit – consistent with tamped-down hunger – but when the ketogenic diet rats switched to a diet with carbs, ghrelin levels soared. At one week post-switch, ghrelin levels were more than double their levels on the ketogenic diet. Ghrelin levels dropped steadily with continued time on the chow diet, returning close to normal around 8 weeks post-switch.

What does this prove? It’s not that surprising that someone coming from a ketogenic diet might be hungry for the first week after adopting a higher-carb diet. It may take more than a week to improve carbohydrate status, reassure the brain that starvation is not imminent, and bring appetite back to normal.

Let me emphasize – such hunger is a rare occurrence at the retreat. People coming to the retreat from SAD diets are generally hunger-free throughout. People coming from low-carb or ketogenic diets typically see their hunger disappear in one to three days. In only two cases – Christine’s and one other – have we seen hunger persist for a full week.

The Bad #2b –Jimmy developed acne

Jimmy wrote:

I was surprisingly NOT hungry eating all of that (but I was pretty well fat-adapted and used to regular periods of extended intermittent fasting of 18-24 hours between meal on keto prior to the retreat). My issue was the sudden outbreak of acne all over my face that was not there before.

The video above was recorded at the end of the retreat, so you can clearly see the quality of Jimmy’s complexion. Judge for yourself whether acne is “all over [his] face.” I see one pimple on his face and one on his neck.

We have had 64 paying attendees at the retreat (15 in May 2014, 22 in October 2014, 27 in May 2015). As far as I know no one but Jimmy has developed pimples while at the retreat. I have a long history of severe acne and while it is far better than it was, I sometimes do develop pimples during the Boston winter. However, they quickly go away when I go to the retreat. So I don’t think the retreat is an acne-promoting environment – far from it.

On the rare occasions pimples do appear on PHD, they can usually be quickly cleared with some nutritional supplements and sunshine. Vitamin A, zinc, and pantothenic acid are typically the supplements most likely to eliminate pimples.

Why might Jimmy have gotten pimples at the retreat? My best guess is that it was a combination of (1) a depleted mucus layer in the gut caused by his carb-starved pre-retreat diet, (2) a sudden rise in his gut bacteria population at the retreat due to a suddenly increased carb and fiber intake, leading to (3) inflammation triggered by direct contact between gut bacteria and intestinal cells, coupled with (4) some nutrient deficiencies that made his skin sensitive to the inflammation.

I’ve blogged on how very low-carb diets can deplete the mucus layer of the gut (see “Dangers of Zero-Carb Diets, II: Mucus Deficiency and Gastrointestinal Cancers,” Nov 15, 2010). This happens because mucin-2, the primary constituent of mucus in the gut, is 80% carbohydrate, and when the body is carb-starved glucose is triaged for the benefit of the brain, starving other tissues like the gut.

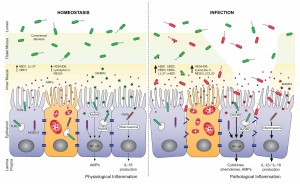

The mucosal layer of the gut generally shields the gut and immune cells lining the digestive tract from direct contact with bacteria. The bacteria they do see are beneficial probiotic mucin-degrading microbes like Akkermansia. A good mucus layer assures an absence of inflammation and a non-permeable gut barrier.

However, when the mucosal layer is depleted, the cells lining our gut are exposed to direct contact to gut bacteria that feed on food. This is inflammatory and also tends to lead to a leaky gut barrier and endotoxemia (entry of bacterial cell wall components into the body). Here’s a picture, from [2]:

My guess is that when Jimmy arrived at the retreat, he had a depleted mucosal layer of the gut, similar to the “INFECTION” side of the image above. However, on his very low carb diet, his gut bacterial population was low, so there wasn’t a lot of inflammation.

When he started eating carbs, his population of gut bacteria soared – bacteria can double their numbers in 20 minutes. It took a week or so to restore a normal mucosal layer. So he had a temporary period that was characterized by a relatively high level of inflammatory signaling coming from the gut.

As our guest Seppo Puusa wrote (“What Causes Acne? An Overview,” Feb 27, 2013), inflammation is the trigger for acne:

[M]ore than anything [acne] is an inflammatory problem. Many researchers now believe that inflammation in the skin is the trigger that kicks off the whole process. Studies have shown that inflammation is present in the very earliest stages of a pimple, even before P. Acnes bacteria colonizes the skin pore.

Antioxidant and immunomodulatory nutrients like vitamin A, zinc, and copper help to prevent pimple formation, while fat disposing nutrients like pantothenic acid help to prevent pore blockage. Jimmy was probably lacking in some of these nutrients, increasing the impact of the inflammation upon his complexion.

Of course this is just speculation, but the general picture is consistent with other aspects of Jimmy’s health. For example, his high LDL is suggestive of a leaky gut and endotoxemia, and recent lab tests indicate a number of nutrient deficiencies.

If I’m right, then Jimmy’s two pimples would have gone away in a little more time on PHD.

The Bad #3 – No info on ketogenic version of PHD

Jimmy wrote:

One thing I was especially looking forward to at the Perfect Health Retreat was learning more about the ketogenic version of Paul’s Perfect Health Diet. He has often noted that there are certain situations where ketones can play a therapeutic role in health–but there was nary a mention of ketosis at all in the hours upon hours of lectures…. [W]hy not share the information about how you recommend going keto for those who do need it?

When we did longer retreats – 30 days and 2 weeks – a discussion of ketogenic diets was part of the curriculum, but with a 1-week curriculum some content had to be dropped. We do health coaching pre-retreat, which allows us to identify any guests who would benefit from a ketogenic diet. So far no such person has come to the retreat. Since none of the guests would benefit from a ketogenic diet, there’s little reason to include it in the curriculum, when we have so much material of general interest.

(Interestingly, Paul would not allow me to give a guest lecture about ketosis as a bonus class for the attendees, but he did let me share a half-hour presentation on cholesterol based on my 2013 book Cholesterol Clarity).

With two days left in the retreat, Jimmy asked me if he could give a talk to the guests. I said sure; but it would have to be in the afternoon – the only free time in the schedule – and I wouldn’t be able to attend because that is when I do one-on-one health coaching. He said he could speak from either of his two books – Keto Clarity and Cholesterol Clarity – and asked which I would prefer. I said I would prefer he do the cholesterol talk, because many of our guests were not familiar with our differences of opinion, and might be confused to hear non-PHD diet recommendations being given with the apparent imprimatur of the retreat, and without me being present to clarify disagreements. Jimmy seemed fine with that at the time, delivered his cholesterol talk, and I heard it was well attended and well received.

I think it is misleading to summarize this conversation with the phrase “Paul would not allow me to lecture about ketosis.” Had I been able to be present and chime in to discuss points of difference, I would have been fine with Jimmy giving his ketogenic diet talk.

Jimmy also states that it is “unfortunate” anyone would think the ketogenic variant of PHD was as good as his no-starch, essentially carb-less diet. (Our ketogenic diet recommends including some starches to avert a deficiency of carbohydrate, fiber and medium-chain triglycerides as sources of ketogenic fatty acids, and a shift of protein toward ketogenic amino acids.) It’s no surprise that we differ on this point, since I think eating some carbs is desirable for everyone, while he thinks carbs are harmful in any dose.

The Ugly #1 – Jimmy Gained Weight

Jimmy wrote:

Many have wondered what would happen to my weight if I truly gave these “safe starches” a go in my diet. Like I said earlier, I told Paul we would do his plan as prescribed just to see what would happen. And the results on the scale were pretty shocking after eating this way for just one week–I gained a whopping 13 pounds!

Let me start my reply to this with a picture:

This picture was taken October 19, 2014, the day after Jimmy left the retreat. (Jimmy was at the retreat October 11-18.) You can see from the comments that Jimmy’s fans think he looks unusually good (“Woohoo! You’re killing it, Jimmy!” “lookin’ handsome Jimmy!! Great job!!” “Lookin’ spiffy!”).

Also note Jimmy’s last statement: he doesn’t know how his weight changed at the retreat. We keep no scales at the retreat, so it was impossible to measure his weight there; and his visit to the retreat was in the middle of a Keto Clarity book tour. He had a series of events in North Carolina following the retreat, and did not have an opportunity to measure his weight until his return home Tuesday, October 21. There must have been a minimum of 11 days between weight measurements, and possibly much longer. Any weight gain he could quantify did not occur in just one week.

If someone did gain 13 pounds in one week, I would expect his face to appear puffy. There is no sign of that in either this image or the video recorded the last day of the retreat.

I looked for a few other full-body images of Jimmy bracketing the retreat. Here is an image dated August 20, 2014 (pre-retreat) from an Asheville, NC Low-Carb meetup:

By eye, I would guess he was not lighter on August 20 than he was on October 19.

Soon after leaving the retreat, Jimmy undertook a long trip, first to San Francisco and then to Australia. Jet lag is a major circadian rhythm disruptor, and as I noted in my AHS talk on weight loss, circadian rhythm disruption is a major cause of obesity. So I wasn’t surprised that in photos from Australia, Jimmy looked heavier. Below is an image from a video of a talk Jimmy gave in Australia in November 2014 placed alongside the above image from October 19.

He looks significantly heavier in November. Immediately after the retreat, his suit jacket hangs straight down at the sides. In November, it bulges out sideways around the waistline.

I find it hard to reconcile this photographic evidence, plus my memory of what I saw in October, with Jimmy’s claim to have gained 13 pounds at the retreat.

Nor did Jimmy eat an inordinate amount of food while at the retreat. He went up for seconds at nearly every meal, but 1.5 to 2 plates per meal adds up to 3000-3500 calories per day, which should be roughly a weight maintenance intake for someone of Jimmy’s size (6’3”).

As my AHS talk on weight loss noted, we’ve had excellent results for weight loss at the retreats. Even in one week, we often see significant weight loss, even with ad libitum eating and wine consumption. For example, in May 2015, our two heaviest guests told me on departure that their pants had become loose and they were cinching their belts in one to two notches.

No guest at the retreats has gained significant weight. I think it would be difficult to do so, since we optimize so many of the weight loss factors.

I think Jimmy is mis-remembering when he gained his weight. He may have gained 13 pounds late last year, but it was probably during his cross-time-zone travels, not the week he spent at our retreat.

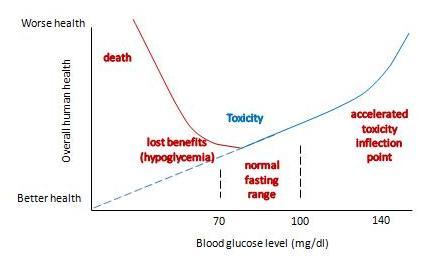

The Ugly #2 – Jimmy’s Blood Sugars Over 100

Jimmy wrote:

Measuring in a fasted state and then measuring postprandial at 30-minute intervals was not a pretty picture. I regularly saw spikes that jumped well above 140 after an hour which is a sign that your body is not tolerating the level of carbohydrates you just consumed. Of course, I was documenting all of this on social media and Paul decided to chime in about it with the following:

“I saw your blood glucose was 149 after lunch. That’s a normal reading, I actually thought it would be higher so I take that as a good sign. It takes a few days to a week to increase insulin sensitivity so it should be better by the end of the week, but even now it is in the normal range.”

I’m sorry, but 149 is NOT normal for me. My postprandial blood glucose readings typically NEVER go above 110-120 at the very most. Generally, the rise in blood sugar is about 20-25 points. But after every meal I consumed on the Perfect Health Retreat, the jump was more like 60-80 points. Not good at all. It took me a few weeks to get my blood sugar back down and under control again after the starchy meals ended. Promoting a starch-based diet to someone with significant insulin resistance is a recipe for disaster.

Jimmy was posting his blood glucose numbers on Instagram and so we have an enduring record.

Jimmy posted about two dozen blood glucose readings from his week at the retreat – I believe, nearly every reading he took – and only one was above 140 mg/dl. Jimmy has always been eager to show that he couldn’t tolerate starches, and if there were any other instances of a blood glucose reading above 140, Jimmy would have posted them to Instagram lickety-split. So I am confident that Jimmy is misremembering when he states, “I regularly saw spikes that jumped well above 140 after an hour.”

His postprandial glucose readings improved steadily throughout the retreat. I’ll just show his earliest and last reports, with links to Instagram:

- The first two postprandial glucose readings Jimmy posted from the retreat were 127 mg/dl one hour after lunch on Sunday October 12, and 149 mg/dl after lunch on Monday October 13.

- After lunch on Friday October 17, the last full day of the retreat, Jimmy’s 90 minute postprandial glucose was 87 mg/dl, and his 120 minute postprandial glucose was 100 mg/dl.

- After our farewell dinner on the evening of Friday October 17, Jimmy recorded his blood glucose every 15 minutes. They were:

- 15 minutes postprandial: 112 mg/dl

- 30 minutes postprandial: 126 mg/dl

- 45 minutes postprandial: 97 mg/dl

- 60 minutes postprandial: 116 mg/dl

- 75 minutes postprandial: 110 mg/dl

- 90 minutes postprandial: 125 mg/dl

- 135 minutes postprandial: 115 mg/dl

- 150 minutes postprandial: 111 mg/dl

- 180 minutes postprandial: 111 mg/dl

These numbers represent a dramatic improvement over the course of the week. Jimmy’s lowest reading on the first two days of the retreat was higher than his highest reading on the last day.

This improvement in insulin sensitivity was expected. Low-carb ketogenic diets are notorious for inducing insulin resistance, leading to high postprandial glucose when carbs are consumed.

This is one of the earliest reported side effects of a ketogenic diet. Recently Sarah Ballantyne and Denise Minger did a literature review on ketogenic diets and offered this image from a 1931 paper [3]:

The deeper the ketosis, the higher blood glucose rises after a carb rich meal. A mere 20 grams of carbs (versus about 125 g in Jimmy’s retreat meals) caused a nearly 30% rise in blood glucose.

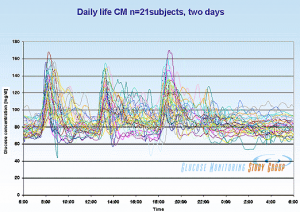

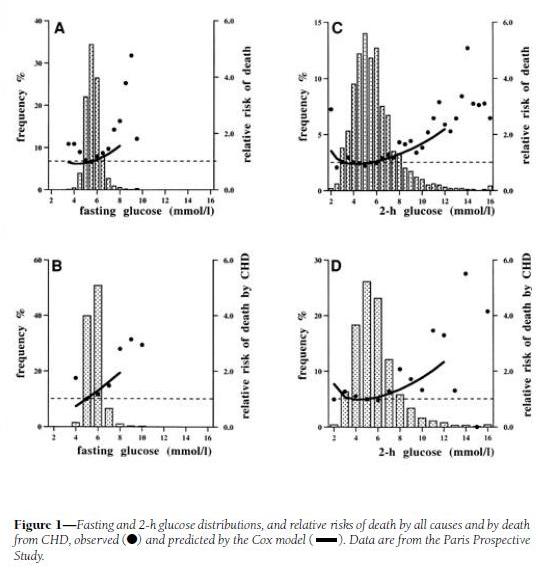

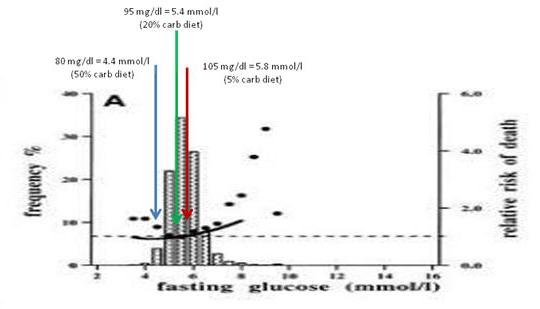

What is a “normal” postprandial glucose reading? Here is a view of postprandial blood glucose levels in healthy (HbA1c 5.4 or less) young people as measured by Professor JS Christiansen (from Ned Kock):

Although most postprandial glucose readings peak about 125 or so, a significant fraction of normal people experience postprandial readings of 149 or higher.

It is within that context that I told Jimmy that it was “normal” for him to have a postprandial reading in the range 127-149 on his first two days at the retreat (coming from a ketogenic diet), and normal to have postprandial readings in the range 97-126 after a week of carb consumption had improved insulin sensitivity.

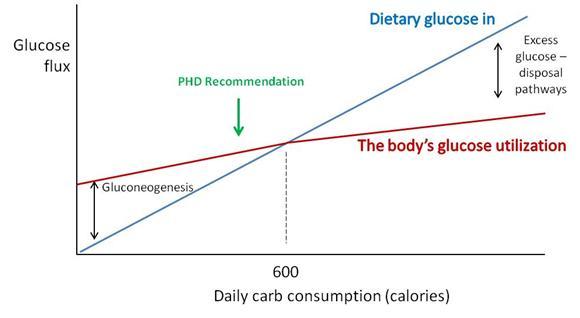

At the retreat, I estimate that Jimmy was eating about 3000 calories per day, about 1/3 of them carbs; about 500 carb calories per meal and 1000 carb calories per day. It is gratifying to see that he is not diabetic, that a week of carb consumption restored his insulin sensitivity, and that he is fully capable of handling PHD levels of carbs.

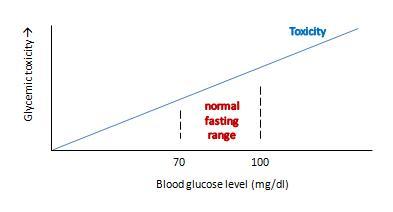

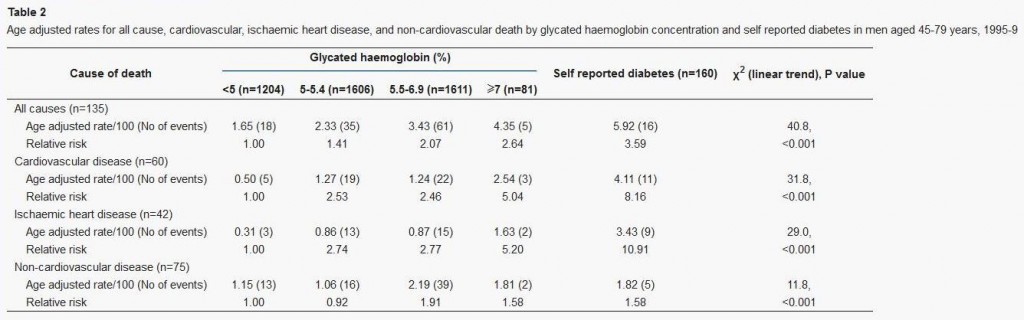

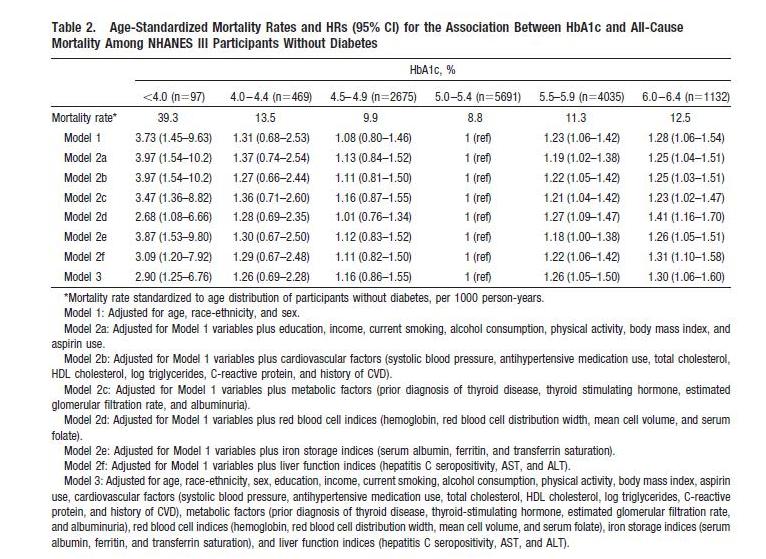

More disturbing were Jimmy’s fasting glucose numbers. Jimmy posted these fasting glucose numbers: 130 mg/dl on Monday, 126 mg/dl on Wednesday, 133 mg/dl on Thursday, and 129 mg/dl on Friday. These are pathological numbers, and worse they showed no improvement during the week.

Jimmy’s fasting glucose numbers are lower on his ketogenic diet, but I do not find this pattern reassuring, for several reasons:

- Jimmy’s numbers are changing for the worse. In his recent “Potpourri of Health Tests,” he reported his history of medical lab tests of fasting glucose: 80 on February 28, 2013; 85 on August 22, 2013; 91 on October 17, 2013; 94 on April 3, 2015; 100 on May 15, 2015.

- Ketones substitute for blood glucose in feeding the brain, and it is the brain that controls blood glucose levels. So it is normal for blood glucose readings to be lower when in ketosis. However, what is important for health are total circulating energy levels (glucose + ketones + free fatty acids); elevated circulating energy poisons the pancreatic beta and alpha cells through “glucolipotoxicity.” [4] To be in ketosis, Jimmy has to have elevated levels of free fatty acids and ketones. So it is alarming that his fasting blood glucose levels while in ketosis are as high as 100 mg/dl.

Note that the loss of pancreatic alpha and beta cells, presumably due to poisoning by glucolipotoxicity, is an observed adverse effect of long-term ketogenic diets [e.g. 5, titled “Long-term ketogenic diet causes glucose intolerance and reduced β- and α-cell mass but no weight loss in mice”]. So possibly Jimmy’s elevated fasting levels of circulating energy substrates is a harbinger of the future development of diabetes.

UPDATE: Another explanation may be more likely. Apparently Jimmy was supplementing 50 mg melatonin. Melatonin is known to raise blood glucose levels in both evening and morning; just 5 mg of melatonin increased maximum night time plasma glucose by 27%. If this is the explanation, then Jimmy’s poor fasting glucose was a result of not following the Perfect Health Retreat program. We have specific supplementation recommendations and melatonin is not among them, except in rare cases where our RD may recommend a therapeutic supplement, in which case we recommend doses below 1 mg.

All this has come about due to Jimmy’s carb-phobia, but ironically Jimmy shows no metabolic signs of an intolerance of carbs. In a Facebook post on May 4, 2015, Jimmy prescribed a test for the healthfulness of “safe starches”:

Try eating a white potato to see how YOU do. Whether it’s truly safe for you will be determined by the impact it makes in your body, especially blood glucose. Measure at fasting (baseline), eat the potato, and then check at 30-minute intervals for at least two hours. At one hour, it should not go higher than 140. At two hours, you should be back close to your baseline. If either of these is awry, you might want to reevaluate your love for white potatoes.

By this test, by Friday at the retreat his “baseline” (fasting glucose) was 129, but eating about 500 calories of carbs in a PHD meal caused his blood glucose to drop postprandially to readings between 97 and 126 – all below his baseline. So white potatoes, if eaten as part of PHD meals, are “truly safe” for Jimmy by his own criterion.

The Ugly #3 – Dogmatic Approach

Jimmy wrote:

[O]ne of the ugliest parts of the Perfect Health Retreat to me was the completely dogmatic approach that it and it alone is the one and only true way to attain optimal health. There was no consideration given to any other means of getting there …

It is hard for me to fathom why it should be “ugly” for me to teach only advice I believe in, and not approaches that I don’t believe in, such as no-starch ketogenic diets.

I know of no health retreat that says, “We not only teach you the ways to achieve health that we believe in; we’ll also teach you the ways we don’t believe in.” I think guests would rightly respond, “Why should I spend time and money to hear you teach me things you believe are health-damaging? I’d rather you make a shorter, cheaper retreat and teach me only what you believe in.” I’m pretty sure Jimmy doesn’t teach the Ornish Diet on his Low Carb Cruises.

Our retreat makes a simple promise. It offers our best advice on how to be healthy. It covers every “ancestral” input to health — diet, nutrition, lifestyle, environment, movement / physical health — and some modern aspects, like understanding lab tests and managing doctors. There is neither time nor interest on my part (or the guests) for me to teach anything other than our best advice.

If someone wants to learn multiple approaches, they can come to our retreat to learn ours, and other events, like Jimmy’s Low Carb Cruise, to learn alternatives.

[Paul holds] staunch, dogmatic views on diet. While there is a lot of good in his plan, the abject close-mindedness to consider anything outside of what he has prescribed is truly unfortunate.

To borrow the Princess Bride line, I’m not sure “dogmatic” and “close-minded” mean what Jimmy thinks they mean.

First, I give evidence for all my recommendations – logical arguments and evidence for every assertion with citations to the literature. Guests at the retreat are given pdf copies of our slide decks, and each slide has its citations printed on it.

Second, I change my mind and update recommendations as I learn. When I first started Paleo I believed in a very low-carb approach, but when it led to health problems I changed my mind. Between the first edition of our book (2010) and the second (2012), a vast number of our recommendations changed — for example, the recommended macronutrient ratios changed from 20% carb 65% fat to 30% carb 55% fat, and nearly all the micronutrient recommendations were revised — based on research I’d done in the meantime, plus experiences of our readers. As an example of changing micronutrient suggestions, I toyed for several years with the possibility that high-dose iodine might be beneficial, before committing to a steady low dose (225 mcg per day) as a firm recommendation. The history of this blog is replete with explorations of issues to which I did not know the answer, and kept an open mind until sufficient evidence and experience gave a reliable answer.

If our dietary advice has recently been stable, it is because we have great confidence in it. We are hearing lots of success stories from people on PHD, essentially no negative outcomes, and new articles in the scientific literature continue to be supportive of our recommendations.

In contrast, I have not seen Jimmy change his mind about anything of substance, in spite of strong evidence which should have led to a reconsideration of his low-carb advice.

Recently, Tom Naughton changed his mind about starches (Safe Starches and The Perfect Health Diet, April 28, 2014):

I noticed more and more people saying they developed problems on a strict very-low-carb diet – low thyroid function, cold hands and feet, high fasting glucose, dry eyes, etc. – which went away when they added some “safe starches” back into their diets as prescribed in the Perfect Health Diet…. So I figured there had to be something to it…. Is the Perfect Health Diet truly the perfect diet? I don’t know, but I was persuaded to move my own diet more in that direction.

We’ve gotten thousands of reader reports of health improvements after switching to PHD from low-carb. Tom and every other prominent person in the ancestral community must have seen hundreds – Jimmy too. And every prominent ancestral leader (unless you count Loren Cordain as a leader) has responded to these experiences by endorsing starches and carbs to some degree. But Jimmy remains as anti-carb as ever.

As his low-carb ketogenic experiment winds on, Jimmy and Christine seem to be developing more of the “Zero Carb Dangers” that I blogged about in 2010-11. For example:

- Kidney stones. In April 2015, Jimmy revealed in a comment on Instagram that Christine was dealing with kidney stones. On November 23, 2010, I noted in “Dangers of Zero-Carb Diets, IV: Kidney Stones,” that low-carb ketogenic diets increase the risk of kidney stones 100-fold. (Ironically, Jimmy devoted a chapter of Keto Clarity to rebutting my critiques of “zero-carb diets,” and stated on page 199, “Kidney stones are the result of a high-carb diet, not a low-carb one.”)

- High LDL. On April 23, 2013, Jimmy revealed in a blog post that his LDL had ranged between 228 mg/dl and 332 mg/dl over the period 2008-2013. In a recent test dated May 15, 2015, Jimmy had an LDL of 194 mg/dl (still very high) despite an iron deficiency anemia (ferritin of 7, serum iron of 23) which is probably depressing his LDL by 30 to 60 mg/dl. I would say that an LDL over 160 is a reliable indicator that something is wrong, and a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In 2011 I made a detailed investigation into why low-carb diets often lead to high LDL levels; see Low Carb Paleo, and LDL is Soaring – Help!” (Mar 2, 2011); Answer Day: What Causes High LDL on Low-Carb Paleo? (Mar 4, 2011); High LDL on Paleo Revisited: Low Carb & the Thyroid (Sep 1, 2011).

Experience shows that there is no amount of evidence that can persuade Jimmy that he is eating too few carbs. Is not his opposition to carb consumption dogmatic?

Summary of the Health Effects of the Retreat on Jimmy

Jimmy’s post suggests that I have overlooked another zero-carb danger: memory loss. After spending the last seven months on an almost carb-free ketogenic diet, Jimmy has forgotten:

- Most of the good aspects of the retreat.

- That his 2014 weight gain occurred after the retreat ended, not during it.

- That his acne at the retreat consisted of one facial pimple, not pimples “all over his face.”

- That his blood glucose went over 140 mg/dl once, not regularly.

- That a week at the retreat made him more insulin sensitive and made eating potatoes and rice “truly safe” for him by his own definition.

In truth, I think the retreat benefited Jimmy’s health. He probably left at his lowest weight, best insulin sensitivity, lowest blood pressure, and lowest LDL cholesterol of the last year. And he left in a joyful, generous mood. Thank you, Jimmy, for your video testimonial.

If his recent blog post about the retreat was less generous, well, I would take that as another indicator that his health has been worsening. Poor health can make one cranky and uncharitable.

More on Jimmy’s Situation

Earlier this week Jimmy posted a comprehensive set of medical labs (“Potpourri of Health Tests,” May 16, 2015). He had a host of abnormal numbers. Follow the link and look at all the red and yellow results.

In interpreting these test results, I think it should be recognized that the various individual issues – such as the iron deficiency anemia, the high anion gap metabolic acidosis, the “euthyroid sick syndrome” pattern of low T3 thyroid hormone (see my post “Carbohydrates and the Thyroid,” Aug 24, 2011), and the low cortisol with a disrupted circadian pattern – are probably reflections of deeper problems caused by malnutrition (starvation of carbs, protein, and assorted micronutrients) despite excess fat intake (a source of metabolic stress). Jimmy is posing metabolic stresses to his body that it is incapable of managing. As a result, his body is failing to perform basic functions like maintaining the circadian rhythm of cortisol or the normal pH (slightly alkaline) of blood.

I hope Jimmy will recognize that his labs (dyslipidemia, glucolipotoxicity, high anion gap metabolic acidosis) suggest that his low-carb ketogenic diet may be putting him at risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and kidney disease.

I like Jimmy and consider him a friend, so I hope he recognizes that this post, and my earlier invitation to our retreat, have been friendly interventions intended to help him.

References

[1] Honors MA, Davenport BM, Kinzig KP. Effects of consuming a high carbohydrate diet after eight weeks of exposure to a ketogenic diet. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009 Nov 19;6:46. http://pmid.us/19925676.

[2] Muniz LR, Knosp C, Yeretssian G. Intestinal antimicrobial peptides during homeostasis, infection, and disease. Front Immunol. 2012 Oct 9;3:310. http://pmid.us/23087688.

[3] Ellis RW. Some Effects of a Ketogenic Diet. Arch Dis Child. 1931 Oct;6(35):285-92. http://pmid.us/21031858/.

[4] Srinivasan VA, Raghavan VA, Parthasarathy S. Biochemical basis and clinical consequences of glucolipotoxicity: a primer. Heart Fail Clin. 2012 Oct;8(4):501-11. http://pmid.us/22999235.

[5] Ellenbroek JH, van Dijck L, Töns HA, Rabelink TJ, Carlotti F, Ballieux BE, de Koning EJ. Long-term ketogenic diet causes glucose intolerance and reduced β- and α-cell mass but no weight loss in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Mar 1;306(5):E552-8. http://pmid.us/24398402.

Recent Comments