One of the more mysterious conditions afflicting low-carb Paleo dieters has been high serum cholesterol. Two of our most popular posts were about this problem: Low Carb Paleo, and LDL is Soaring – Help! (Mar 2, 2011) enumerated some cases and asked readers to suggest answers; Answer Day: What Causes High LDL on Low-Carb Paleo? (Mar 4, 2011) suggested one possible remedy.

On the first post, one of the causes suggested by readers was hypothyroidism – an astute answer. Raj Ganpath wrote:

Weight loss (and VLC diet) resulting in hypothyroidism resulting in elevated cholesterol due to less pronounced LDL receptors?

Kratos said “Hypothyroidism from low carbs.” Mike Gruber said:

I’m the guy with the 585 TC. It went down (to 378 8 months or so ago, time to check again) when I started supplementing with iodine. My TSH has also been trending up the last few years, even before Paleo. So hypothyroidism is my primary suspect.

Those answers caused me to put the connection between hypothyroidism and LDL levels on my research “to do” list.

Chris Masterjohn’s Work on Thyroid Hormone and LDL Receptors

Chris Masterjohn has done a number of blog posts about the role of LDL receptors in cardiovascular disease. His talk at the Ancestral Health Symposium was on this topic, and a recent blog post, “The Central Role of Thyroid Hormone in Governing LDL Receptor Activity and the Risk of Heart Disease,” provides an overview.

His key observation is that thyroid hormone stimulates expression of the LDL receptor (1). T3 thyroid hormone binds to thyroid hormone receptors on the nuclear membrane, the pair (a “dimer”) is then imported into the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor causing, among other effects, LDL receptors to be generated on the cell membrane.

So higher T3 = more LDL receptors = more LDL particles pulled into cells and stripped of their fatty cargo. So high T3 tends to reduce serum LDL cholesterol levels, but give cells more energy-providing fats. Low T3, conversely, would tend to raise serum cholesterol but deprive cells of energy.

Other Pieces of the Puzzle

Two other facts we’ve recently blogged about help us interpret this result:

- LDL particles are not only lipid transporters; they also have immune functions. See Blood Lipids and Infectious Disease, Part I, Jun 21, 2011; Blood Lipids and Infectious Disease, Part II, Jul 12, 2011.

- T3 becomes low when glucose or protein are scarce. Thyroid levels alter to encourage resource utilization when resources are abundant and to conserve resources when they are scarce. See Carbohydrates and the Thyroid, Aug 24, 2011.

We can now assemble a hypothesis linking low carb diets to high LDL. If one eats a glucose and/or protein restricted diet, T3 levels will fall to conserve glucose or protein. When T3 levels fall, LDL receptor expression is reduced. This prevents LDL from serving its fat transport function, but keeps the LDL particles in the blood where their immune function operates.

If LDL particles were being taken up from the blood via LDL receptors, they would have to be replaced – a resource-expensive operation – or immunity would suffer. Apparently evolution favors immunity, and gives up the lipid-transport functions of LDL in order to maintain immune functions during periods of food scarcity.

High LDL on Low Carb: Good health, bad diet?

Suppose LDL receptors are so thoroughly suppressed by low T3 that the lipid transport function of LDL is abolished. What happens to LDL particles in the blood?

Immunity becomes their only function. They hang around in the blood until they meet up with (bacterial) toxins. This contact causes the LDL lipoprotein to be oxidized, after which the particle attaches to macrophage scavenger receptors and is cleared by immune cells.

So, if T3 hormone levels are very low and there is an infection, LDL particles will get oxidized and cleared by immune cells, and LDL levels will stay low. But if there is no infection and no toxins to oxidize LDL, and the diet creates no oxidative stress (ie low levels of omega-6 fats and fructose), then LDL particles may stay in the blood for long periods of time.

If LDL particles continue to be generated, which happens in part when eating fatty food, then LDL levels might increase.

So we might take high LDL on Paleo as a possible sign of two things:

- A chronic state of glucose deficiency, leading to very low T3 levels and suppressed clearance of LDL particles by lipid transport pathways.

- Absence of infections or oxidative stress which would clear LDL particles by immune pathways.

The solution? Eat more carbs, and address any remaining cause of hypothyroidism, such as iodine or selenium deficiency. T3 levels should then rise and LDL levels return to normal.

Alternatively, there is evidence that some infections may induce euthyroid sick syndrome, a state of low T3 and high rT3, directly. And these infections may not oxidize LDL, thus they may not lead to loss of LDL particles by immune pathways. So such infections could be another cause of high LDL on Paleo.

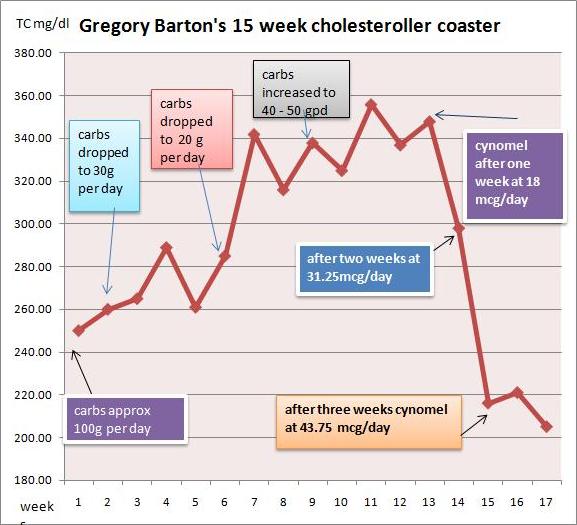

Gregory Barton’s Experience

Gregory Barton is an Australian, 52 years old, living in Thailand, where he keeps goats, makes goat cheese and manages a large garden which can be seen on http://www.asiagoat.com/.

Gregory left a comment with an intriguing story, and I invited him to elaborate in a post. Here’s Gregory’s story. – Paul

Gregory’s Writing Begins Here

One of the claims of low carb dieting is that it will normalize the symptoms of metabolic syndrome. Blood pressure, blood sugar and blood lipids, it is claimed, will all come down on a low carb diet, in addition to weight. For most people this happens. But there is a significant minority of people on Paleo and other low carb diets whose blood lipids defy this claim. (See the list of low-carb celebrities with high LDL in this post.)

Why should this happen? Why should some people’s lipids fall on low carb while other people’s lipids rise? Suboptimal thyroid might be the proximate cause for lipids rising on a low carb or paleo diet. Broda Barnes and Lawrence Galton have this to say about thyroid disorders:

“Of all the problems that can affect physical or mental health, none is more common than thyroid gland disturbance. None is more readily and inexpensively corrected. And none is more often untreated, and even unsuspected.” — Hypothyroidism: The Unsuspected Illness

I went very low carb in April in an effort to address metabolic issues, eating as little as 15grams carbohydrate per day. I had great results with blood pressure, sleeping, blood sugar and weight loss. But lipids bucked the trend.

I had expected triglycerides and cholesterol to drop when I cut the carbs, but they did the opposite: They surged. By July my total cholesterol was 350, LDL 280, and triglycerides bobbed around between 150 and 220.

I did some research and found several competing theories for this kind of surge:

- Saturated fat: The increase in saturated fat created a superabundance of cholesterol which the liver cannot handle. Also, Loren Cordain has claimed that saturated fat downregulates LDL receptors.

- Temporary hyperlipidemia: The surge in lipids is the temporary consequence of the body purging visceral fat. Jenny Ruhl has argued that within a period of months the situation should settle down and lipids should normalize.

- Hibernation: The metabolism has gone into “hibernation” with the result that the thyroid hormone T4 is being converted into rT3, an isomer of the T3 molecule, which prevents the clearance of LDL.

- Malnutrition: In March, Paul wrote that malnutrition in general and copper deficiency in particular “… is, I believe, the single most likely cause of elevated LDL on low-carb Paleo diets.”

- Genetics: Dr. Davis has argued that some combinations of ApoE alleles may make a person “unable to deal with fats and dietary cholesterol.”

I could accept that saturated fat would raise my cholesterol to some degree. However, I doubted that an increase in saturated fat, or purging of visceral fat, would be responsible for a 75% increase in TC from 200 to 350.

There are two basic factors controlling cholesterol levels: creation and clearance. If the surge was not entirely attributable to saturated fat, perhaps the better explanation was that the cholesterol was not being cleared properly. I was drawn to the hibernation theory.

But what causes the body to go into hibernation? According to Chris Masterjohn, a low carb diet could be the cause. Although he does not mention rT3, he warns,

“One thing to look out for is that extended low-carbing can decrease thyroid function, which will cause a bad increase in LDL-C, and be bad in itself. So be careful not to go to extremes, or if you do, to monitor thyroid function carefully.”

If low carb is the cause, then higher carb should be the cure. Indeed, Val Taylor, the owner of the yahoo rT3 group, commented that “it is possible that the rT3 could just be from a low carb diet.” She says, “I keep carbs at no lower than 60g per day for this reason.”

Cortisol and Getting “Stuck” in Hibernation

So what about temporary hyperlipidemia? Bears hibernate for winter, creating rT3, but manage to awaken in spring. Why should humans on low carb diets not be able to awaken from their hibernation? There are many people who complain of high cholesterol years after starting low carb.

A hormonal factor associated with staying in hibernation is high cortisol. It has been claimed that excessively high or low cortisol, sustained over long periods, may cause one to get “stuck” in hibernation mode. One of the moderators from the yahoo rT3 group said:

High or low cortisol can cause rT3 problems, as can chronic illness. It would be nice if correcting these things was all that was necessary. But it seems that the body gets stuck in high rT3 mode.

James LaValle & Stacy Lundin in Cracking the Metabolic Code: 9 Keys to Optimal Health wrote:

When a person experiences prolonged stress, the adrenals manufacture a large amount of the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol inhibits the conversion of T4 to T3 and favours the conversion of T4 to rT3. If stress is prolonged a condition called reverse T3 dominance occurs and lasts even after the stress passes and cortisol levels fall. (my emphasis)

What I Did

First, I got my thyroid hormone levels tested. A blood test revealed that I had T4 at the top of the range and T3 below range. Ideally I would have tested rT3, but in Thailand the test is not available. I consulted Val Taylor, the owner of the yahoo rT3 group, who said that low T3 can cause lipids to go as high as mine have and, “as you have plenty of T4 there is no other reason for low T3 other than rT3.”

I decided to make these changes:

- Increase net carbs to ~50 grams per day. Having achieved my goals with all other metabolic markers I increased carbs, taking care that one hour postprandial blood sugar did not exceed 130 mg/dl.

- Supplement with T3 thyroid hormone.

- In case the malnutrition explanation was a factor, I began supplementing copper and eating my wife’s delicious liver pate three times per week.

I decided to supplement T3 for the following reasons:

- The surge in TC was acute and very high. It was above the optimal range in O Primitivo’s mortality data.

- I increased carbs by 20-30g/day for about a month. TC stabilized, but did not drop.

- The rT3 theory is elegant and I was eager to test my claim that the bulk of the cholesterol was due to a problem with clearance rather than ‘superabundance’.

What happened?

I started taking cynomel, a T3 supplement, four weeks ago. After one week triglycerides dropped from 150 to 90. After two weeks TC dropped from 350 to 300 and after another week, to 220. Last week numbers were stable.

Based on Paul’s recent series on blood lipids, especially the post Blood Lipids and Infectious Disease, Part I (Jun 21, 2011), I think TC of 220 mg/dl is optimal. As far as serum cholesterol levels are concerned, the problem has been fixed.

I believe that thyroid hormone levels were the dominant factor in my high LDL. Saturated fat intake has remained constant throughout.

My current goal is to address the root causes of the rT3 dominance and wean myself off the T3 supplement. I hope to achieve this in the next few months. My working hypothesis is that the cause of my high rT3 / low T3 was some combination of very low carb dieting, elevated cortisol (perhaps aggravated by stress over my blood lipids!), or malnutrition.

Another possibility is toxins: Dr Davis claims that such chemicals as perchlorate residues from vegetable fertilizers and polyfluorooctanoic acid, the residue of non-stick cookware, may act as inhibitors of the 5′-deiodinase enzyme that converts T4 to T3. Finally, Val Taylor claims that blood sugar over 140 mg/dl causes rT3 dominance. I couldn’t find any studies confirming this claim, and don’t believe it is relevant to my case. Val recommends low carb for diabetics to prevent cholesterol and rT3 issues but warns not to go under 60g carb per day.

Issues with T3 Supplementation

There are some factors to consider before embarking upon T3 supplementation:

- Preparation: In order to tolerate T3 supplement you have to be sure that your iron level and your adrenals are strong enough. This requires quite a bit of testing. I’ve read of people who cut corners with unpleasant results.

- Practicalities: T3 supplementation requires daily temperature monitoring in order to assess your progress. People who are on the move throughout the day would find this difficult.

- Danger: Once you get on the T3 boat you can’t get off abruptly. Your T4 level will drop below range and you will be dependent on T3 until you wean yourself off. If you stopped abruptly you could develop a nasty reaction and even become comatose.

My advice for anyone doing very low carb

As Chris Masterjohn said, in the quote above, if you are going to do very low carb, check your thyroid levels. I would add: Increase the carbs if you find your free T3 falling to the bottom of the range. It might be a good idea to test also for cortisol. A 24-hour saliva test will give you an idea whether your cortisol levels are likely to contribute to an rT3 issue. It might also be a good idea to avoid very low carb if you are suffering from stress – such as lipid anxiety!

Gregory Barton’s Conclusion

I also think my experience may help prove thyroid hormone replacement to be an alternative, and superior, therapy to statins for very high cholesterol. Statins, in the words of Chris Masterjohn,

“… do nothing to ramp up the level of cholesterol-made goodies to promote strength, proper digestion, virility and fertility. It is the vocation of thyroid hormone, by contrast, to do both.”

Paul’s Conclusion

Thanks, Gregory, for a great story and well-researched ideas. The rapid restoration of normal cholesterol levels with T3 supplementation would seem to prove that low T3 caused the high LDL levels.

However, I would be very reluctant to recommend T3 supplementation as a treatment for high LDL on Paleo. If the cause of low T3 is eating too few carbs, then supplementing T3 will greatly increase the rate of glucose utilization and aggravate the glucose deficiency.

The proper solution, I think, is simply to eat more carbs, to provide other thyroid-supporting nutrients like selenium and iodine, and allow the body to adjust its T3 levels naturally. The adjustment might be quite rapid.

In Gregory’s case, his increased carb consumption of ~50 g/day was still near our minimum, and he may have been well below the carb+protein minimum of 150 g/day (since few people naturally eat more than about 75 g protein). So I think he might have given additional carbs a try before proceeding to the T3.

Gregory had a few questions for me:

GB: What if one is glucose intolerant and can’t tolerate more than 60 grams per day without hyperglycemia or weight gain?

PJ: I think almost everyone, even diabetics, can find a way to tolerate 60 g/day dietary carbs without hyperglycemia or weight gain, and should.

GB: What if raising carbs doesn’t normalize blood lipids and one finds oneself ‘stuck in rT3 mode’?

PJ: I’m not yet convinced there is such a thing as “stuck in rT3 mode” apart from being “stuck in a diet that provides too few carbs” or “stuck in a chronic infection.” If one finds one’s self stuck while eating a balanced diet, I would look for infectious causes and address those.

Finally, if I may sound like Seth Roberts for a moment, I believe this story shows the value of a new form of science: personal experimentation, exploration of ideas on blogs, and the sharing of experiences online. It takes medical researchers years – often decades – to track down the causes of simple phenomena, such as high LDL on low carb. We’re on pace to figure out the essentials in a year.

Recent Comments