Stephan Guyenet recently did a great podcast with Chris Kresser, discussing the relationship between food reward and obesity. At his blog Whole Health Source he has been expanding upon the podcast with a series titled “Food Reward: A Dominant Factor in Obesity.”

Stephan is a neurobiologist and an expert in the role of the brain in obesity – something I know little about – so it was delightful to have a chance to learn from him.

Today I will try to place Stephan’s ideas in a larger context. I will argue that the concept of a fat mass setpoint is best understood as a dynamic equilibrium among many organs of the body, including the brain; and that food reward is a very important factor in the obesity epidemic because it helps explain many aspects of weight gain and loss and explains why many people are so eager to eat toxic and malnourishing foods, but that it may be going too far to call it a “dominant” factor in obesity.

Metabolic Damage

In some ways I think we know about the causes of obesity than about its nature. It’s very easy to induce obesity in both animals and humans: feed a malnourishing diet providing calories in the form of a combination of wheat, fructose, and polyunsaturated fats. The links between these toxic foods and obesity are discussed in our book and in several blog posts (see Why We Get Fat: Food Toxins, Jan 20, 2011, and Wheat and Obesity: More from the China Study, Sep 4, 2010). Malnutrition contributes to obesity by promoting metabolic syndrome and appetite (see Choline Deficiency and Plant Oil Induced Diabetes, Nov 12, 2010).

Grains, fructose sugars, and omega-6 vegetable oils provide about 60% of calories in the modern diet, up from less than 10% in the Paleolithic. The strongest rise has been in omega-6 and fructose consumption since about 1970. At the same time, there has been a shift from home cooking of fresh foods to industrially processed and preserved foods. Lack of freshness and industrial processing can significantly increase food toxicity. With these shifts, obesity rates have skyrocketed.

It seems clear that these toxic, malnourishing diets can induce “metabolic damage”: biological changes that alter the way energy is metabolized and energy expenditure is managed – changes that bring about and maintain obesity.

What Are the Sites of Metabolic Damage?

In the obese, altered biology has been detected in many organs. Examples include:

- Liver

- Adipose tissue

- Brain

- Skeletal muscle

- Gut and gut flora

- Endocrine organs (thyroid, adrenals, pituitary)

Metabolic damage is a complex topic in part because so many parts of the body experience it, and interactions between these organs are crucial to understanding obesity.

Any good theory of obesity will have to explain the damage that occurs in all of these organs. It will also have to explain the interactions and interdependencies among these organs.

Stephan: The Brain’s Sub-Systems Matter

Stephan has taught us an important fact: that the brain has two connected but somewhat independent organs that participate in obesity:

- The energy homeostasis system

- The food-reward system

The energy homeostasis system is located in the hypothalamus and listens to the hormone leptin, which is released by adipose cells. More leptin indicates more fat mass (but not everyone has the same leptin level for the same amount of fat). The energy homeostasis system adjusts activity and thermogenesis (“calories out”) to achieve its desired leptin level – which translates to a desired fat mass “setpoint.”

The food-reward system influences appetite (“calories in”). It evolved for the purpose of getting us to eat the most healthful and beneficial foods. Thus, starches and fats, staples of the Perfect Health Diet, are good at stimulating the food reward system. Eating large amounts of a single flavor is boring; variety – which minimizes the dose of any one toxin, and ensures a diversity of nutrients – is higher in reward.

So one part of the brain manages “calories in” with an eye toward being well nourished, while another part manages “calories out” with an eye toward achieving just the right amount of fat.

What could go wrong?

Misdirected Food Reward

Unfortunately, a reward system that evolved in the Paleolithic is not necessarily a good guide to navigating modern foods:

- New foods have come into existence – agriculturally produced cereal grains, hybridized for greater toxicity; refined fructose-rich sugars; and vegetable seed oils high in omega-6 – that didn’t exist in our evolutionary past. These toxic but malnourishing foods confuse the food reward system by invoking the same signals highly nutritious Paleo foods do – starch; fat; salt – but lack nutritional value, and indeed can act as poisons.

- Food scientists have learned how to design toxic and malnourishing foods that hyperstimulate the food reward system. They stimulate addictive behavior: when you eat one, you want another one, and another. All aspects of the food are designed to trick the food reward system into wanting more – even color.

In this modern environment of industrially processed toxic foods, following our innate food preferences may easily lead us to eat unhealthy diets. It may also lead us to eat more calories than we need, creating a “positive energy balance” that Stephan associates with inflammation.

Food Reward Paradoxes

Food reward is rather hard to make sense of. Many commenters have noted this, and Stephan had to do a post clarifying what he means by food reward:

Food reward is the process by which eating specific foods reinforces behaviors that favor the acquisition and consumption of the food in question. You could also call rewarding food “reinforcing” or “habit-forming”, although not necessarily in an addictive sense.

A seeming paradox is this: On the one hand, the food reward system evolved to guide us toward healthy foods, as Stephan says:

Food reward is essential for survival in a natural environment, because it teaches you what to eat …

Yet in the modern environment eating high-reward foods is supposed to impair health and cause obesity.

This is of course consistent with our view of obesity – modern industrial foods are toxic and malnourishment – but the mechanisms involving the food reward system are still a bit confusing.

One confusing aspect is that Stephan has spoken of the reward value of macronutrients, with carbs and fat being generally more rewarding than protein, and a carb-fat mix being most rewarding.

This does explain certain observed facts: that “lean meat and vegetables” diets, which are high in protein and therefore low in food reward, tend to induce immediate weight loss. Many popular diet books – Atkins, the Eades Protein Power books, the Dukan Diet – recommend such diets; immediate weight loss helps the diets go viral.

Yet it is not clear that it is consistent with all the facts. In particular high food reward may be consistent with good or ill health, obesity or slenderness. Some of the healthiest weight loss diets, such as ours, are high in food reward (see Low-Protein Leanness, Melanesians, and Hara Hachi Bu, Jan 27, 2011; Perfect Health Diet: Weight Loss Version, Feb 1, 2011).

The food reward system evolved to make us healthier. So it would seem to be the modern environment, especially newly available types of high-reward but unhealthy food, that is the cause of obesity. Food reward enters into obesity only because the food reward system no longer guides us to the optimal foods.

On our view, that toxicity is what matters most, the combination of wheat and fructose with polyunsaturated fats creates obesity, while the combination of safe starches with saturated and monounsaturated fats makes one slender. Yet both may have the same proportions of carb and fat! So it is not clear why food reward is a “dominant factor in obesity” if obesity-causing and obesity-curing diets may have similar food reward.

One possible explanation is that food reward is strongly influenced by subtle changes in the intensity of flavors and flavor associations. Seth Roberts today has a post illustrating this: a reader lost almost all excess weight simply by shifting from Coke and Pepsi to iced tea flavored with a cup of sugar per gallon. Seth writes:

His drink was pleasant enough. It derived pleasure from flavor (tea), sweetness (sugar), and sourness (lemon juice).

Of course Coca-Cola is flavored, sweet, and acidic. Why does one drink cause weight loss and the other obesity?

Seth’s correspondent had drank the iced tea daily for 3 years. If rewarding food is food that people keep returning to, then it seems the iced tea was as rewarding as the Coca-Cola. On the other hand, if the only way we have to judge that iced tea is low in food reward is that it leads to weight loss, or that Coca-Cola is high in food reward is that it leads to weight gain, then the theory becomes circular. Is there some independent way of judging food reward?

Toward a Food-Reward Theory of Obesity

To expand this into a theory of obesity, one has to address both the “calories in” and “calories out” sides of the equation; and also the “body composition” issue – if you have more calories in than out, where do they go? To fat or muscle?

Food reward obviously influences “calories in.” But to be “a dominant factor in obesity” the food reward system has to influence “calories out” as well. How does it do this?

Stephan believes that there is “reciprocal regulation” between the food reward system and the brain’s energy homeostasis system, so that when highly rewarding food is available the food reward system persuades the hypothalamus to accept a higher fat mass.

I’m not aware that Stephan has indicated whether he thinks the food reward system can have any influence on body composition.

So the food-reward theory of obesity seems to be only a partial explanation of obesity. Yet there is evidence for it.

Evidence: Weight Plateaus

The greatest merit of the theory is that it explains why weight tends to reach plateaus and stay at specific weights as long as the diet remains unchanged.

I’ve previously shown this plot from Seth Roberts:

Note how every time he adopted a new diet or lifestyle, weight changed rapidly at first and then settled at a plateau. On low-carb, Alex lost 50 pounds in his first year and then spent most of 2003 at 200 pounds with little change. On the Shangri-La diet he lost 30 pounds in six months and then spent a year at a plateau of 190 pounds. A vegan diet moved him to a plateau at 230 pounds, where he seems to have spent about 8 months.

This is exactly what the food-reward theory predicts. A diet stimulates the food-reward system and leads to setting of the fat mass setpoint. Different food rewards, different setpoints. Manipulating food reward, as in Shangri-La Diet or low-carb high-protein dieting, lowers the setpoint.

But here are two things to consider:

(1) There is no evidence that the setpoint that is ultimately reached is the optimal weight. Often the plateau weight is still abnormally high, even on low-carb Paleo or Shangri-La Diets.

(2) There is no evidence that reaching a “normal” weight through a low food reward diet is the same as achieving health.

I think we have to ask the question: what is our goal? Is it weight loss, or is it returning to optimal health? If the latter, does a diet that achieves weight loss by manipulating food reward improve health?

This issue came up in the podcast and Stephan’s answer was that a low food reward diet reduces calorie intake leading to negative or neutral energy balance. In many studies, positive energy balance is associated with increasing inflammation while calorie restriction is associated with improved biomarkers and reduced inflammation. So low food reward diets may well be health improving.

I think this quite likely, but here are two possible objections:

(1) Low food reward dieting has transient and reversible benefits. The period of positive or negative energy balance is transient on all diets; eventually weight settles at a plateau and neutral energy balance is once again attained. So if energy balance is all that matters, the health benefits of a low food reward diet will also be transient. If the low food reward diet is not maintained for life, then eventually a switch to a higher food reward diet will introduce a period of health damage that may exactly compensate for the benefits won during the transition to the low food reward plateau.

(2) Low food reward dieting is suboptimal for health. If food reward evolved to lead us to the healthiest diet in the evolutionary milieu, isn’t the best health to be achieved by eating for HIGH food reward and living in the evolutionary style eating evolutionary foods?

The first issue tells us that for real health benefits, the low food reward diet has to be a lifelong practice, or else there has to be an independent effect of fat mass on health, with elevated fat mass impairing health regardless of energy balance.

The second issue is particularly interesting in light of the fact that some aspects of Stephan’s diet, which he describes in his podcast with Chris Kresser, seem designed to reduce the food reward of his diet. For instance, he minimizes spices or salt, and avoids between-meal snacks.

Salt is a source of food reward. It also may improve health, as it seemed to do in the recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which people eating 6 g/day (highest third of salt consumption) were only one-fifth as likely to die of heart disease as people eating less than 2.5 g/day (lowest third).

So should we target low food reward, or high food reward but with evolutionary foods in an evolutionary lifestyle?

Our weight loss advice (See Perfect Health Diet: Weight Loss Version, Feb 1, 2011) is essentially the latter. We favor a mixed carb and fat diet with savory sauces and broths that includes high food-reward items like salt. We disagree with the “lean meat and vegetables” approach to weight loss dieting, although we acknowledge that it usually brings on rapid initial weight loss.

I should say that Stephan’s diet, described in the podcast, is very close to ours. It could be described as a high-carb version of the Perfect Health Diet, with diversity of carbs increased by using detoxification procedures like soaking, sprouting, and fermenting to increase the number of “safe starches.” In describing his diet, he mentioned eating rice but not other cereal grains.

So it seems the differences between Stephan’s diet and ours are rather subtle. But one could argue that the differences between the sugared iced tea and Coca-Cola which Seth’s correspondent drank are also subtle. In the food reward theory of obesity, little changes in flavor can make a big difference in weight.

Does Food Reward Explain Obesity – Or Weight?

I think it’s important to distinguish between the disease of obesity – the health disorder characterized by metabolic damage – and the condition of being fat. Consider:

- An obese person whose metabolic damage was suddenly and completely cured would be healthy but still fat, because it would take some time to lose weight. But the weight would fall off rapidly.

- One could be slender and yet still have the disease of obesity, if metabolic damage persisted. If the site of metabolic damage is elsewhere than adipose cells, then liposuction might make a person slender but it wouldn’t cure obesity. The weight would return. This is in fact what happens.

Looking back at Alex Chernavsky’s weight chart, it’s clear that low-carb and Shangri-La diets reduced his weight. It’s not obvious that any diet cured his obesity.

Likewise, we’re all familiar with young people who eat massive quantities of junk food and remain slender. The high food reward diets, even toxic and malnourishing diets, seem not to cause weight gain until some kind of metabolic damage occurs.

It seems that metabolic damage – the disease of obesity – is a prerequisite for food reward to matter.

Stabby found an interesting paper that addresses this. They write:

Only some of the leptin-resistance models (leptin antagonist blockade and aged obese rats) exhibit heightened weight and adiposity gain on a chow diet, while all models discussed demonstrate obesity in the presence of an HF diet. Thus, the leptin resistance appears to be reinforcing “reward eating” beyond caloric energy requirements….

Leptin receptors … act through the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and decrease food consumption upon leptin action. The fact that a chronic reduction in leptin receptor activity in the VTA by siRNA knockdown enhances sensitivity to highly palatable food underscores an important role of leptin receptor function in the regulation of reward feeding behavior (24).

In other words, leptin resistance may have to exist before high-reward foods induce “reward feeding behavior,” or excessive consumption of calories. Likely it has to exist also before the fat mass setpoint is altered from normal.

If obesity (the disease) must exist before food reward becomes a factor in obesity, then it hardly seems likely that food reward is a dominant factor in obesity the disease. It is rather a dominant factor in how much an obese person weighs. That is a different thing.

Fat Mass Setpoint as a Dynamic Equilibrium

Early in this post I listed a half dozen sites of metabolic damage; the brain was only one. I believe that the fat mass setpoint is not controlled by any one metabolic organ, but rather that it is a dynamic equilibrium that is influenced by the whole body.

In other words: metabolic damage anywhere will affect the fat mass setpoint. The brain is not unique in its metabolic role. There are a myriad of ways to alter the fat mass setpoint, and they don’t all involve food, the food reward system, or even the brain.

Is the Brain the Pre-Eminent Site of Metabolic Damage?

Food reward looks to be important because changing the food reward of the diet changes the fat mass setpoint. Reduce food reward and weight drops; raise food reward and weight (usually) increases. This occurs in humans as well as lab animals, as Alex Chernavsky’s chart shows.

But all this really shows us is that food reward is a lever that we can use to adjust weight. It doesn’t tell us that it is the only or most important lever.

Food reward is a very easy lever for scientists to manipulate. It’s easy to replace rodent chow with Cheetos and see what happens. It’s a bit harder to adjust the state of the liver, the adipose tissue, the thyroid, or skeletal muscle.

When those other sites of metabolic damage are manipulated, does the fat mass setpoint change as dramatically as it does when food reward is manipulated?

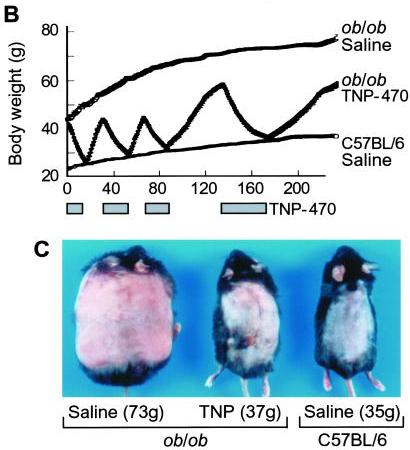

I think it does. Consider this classic study by Maria Rupnick and colleagues. Giving or withholding angiogenesis inhibitors causes mice to cycle between obese and normal weight:

In some ways this weight cycling is more dramatic than any of the food reward studies, because weight in leptin-impaired (ob/ob) mice goes all the way back to normal with angiogenesis inhibition. And it is thought that the angiogenesis is occurring purely in adipose tissue, not in the brain – so it would seem that this is a clean manipulation of adipose tissue only. Perhaps adipose tissue angiogenesis is a “dominant factor in obesity.”

Many other manipulations of adipose tissue change the equilibrium weight (the “fat mass setpoint”). For instance:

- The level of activation of PPAR-gamma affects the amount of leptin released per unit fat mass. PPAR-gamma deficiency leads to hypersecretion of leptin from adipocytes; mice become very slender and adipocytes very small because the brain thinks the body is fat. These mice never develop insulin resistance. PPAR-gamma can be influenced by diet.

- The number of eosinophils – a type of white blood cells – controls whether adipose tissue macrophages are in a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory state. This in turn controls whether adipose cells are insulin resistant or insulin sensitive, with implications for obesity and diabetes. This is one possible pathway by which gut flora may affect obesity, since the types of gut flora influence eosinophil counts.

It’s starting to look like metabolic damage in the adipose tissue alone may be sufficient to induce obesity.

We’ve previously discussed the fact that choline deficiency induces obesity, primarily (it is thought) through effects in the liver. It is likely that alternating high-choline and zero-choline diets would induce fluctuations similar to those in Maria Rupnick’s angiogenic mice. Choline deficiency induced obesity suggests that metabolic damage to the liver alone may be sufficient to induce obesity.

It may be that every organ with a role in metabolic regulation can be manipulated in some way to induce obesity. It looks like the fat mass setpoint is a dynamic equilibrium which depends on the state of every one of the organs involved in metabolic regulation.

If every site of metabolic damage matters and is influential on weight, then it would seem an exaggeration to describe food reward as a dominant factor in obesity. It is an important factor, but not obviously more important than any of the other systems or organs involved in metabolic regulation.

Conclusion

I am grateful to Stephan for sharing his knowledge of the food reward system and the neurobiology of obesity. I immensely enjoyed listening to his podcast and reading his blog posts, and look forward even more to future posts so I can chase references.

But nothing he said has caused me to change my views of obesity or of the best weight loss diet:

- I think the focus should be on recovering health by curing metabolic damage.

- I think our evolved preference for tasty foods including starches, fat, salt, and other “high reward” flavors indicates they are healthy, and therefore that a diet rich in such foods is most likely to cure metabolic damage.

- I think it is essential to stay away from toxic, malnourishing foods made from wheat, fructose sugars, omega-6 oils, and bioactive compounds like MSG; and instead to eat foods that accord with our evolutionary history.

In one sense I think Stephan is right to call food reward a dominant factor in the obesity epidemic. If industrial food designers weren’t trying to make toxic foods rewarding, we might not have an obesity epidemic. People consume large quantities of toxic malnourishing foods because industrial food designers have learned how to conceal their poor taste and make them hyperstimulate our food reward system.

But looking at biology, I have a hard time believing that the food reward system in the brain is a dominant site of metabolic damage. The liver, adipose tissue, and hypothalamus seem likelier candidates to me. So if your goal is not merely to manipulate weight, but to cure the disease of obesity, then I think it is necessary to look not at food reward, but at food toxicity, nutrition, chronic infections, and gut flora. Those are the levers the obese should look to for a cure.

Exactly. and I’m sure Stephan agrees in the end, there’s more at work here than just palatability in determining our food reward and how much we’re driven to eat. Palatablity produces preferences (beginning of a sweet alliteration) in the absence of particular inhibitions, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that we’re going to eat so much of those foods that by virtue of calories alone we’ll gain weight. There is the monotony factor as somewhat of a counter but leptin is clearly a mediator of that. That’s not to say that ultra-stimulating junk food wouldn’t have an effect on food reward, I just wonder how big a deal it is when everything else is working in our favor.

I agree with saying no to bland food. I actually do think that palatability affects food reward in the case of good leptin signaling and real food, I seem to need a certain degree of deliciousness to eat enough calories to gain and maintain muscle. That would be an example of the genes in their environment of adaptation doing what they do best.

Cheers, this is one of the most fascinating subjects I have encountered. So much potential for good in sorting this whole issue out, it’s exciting.

You write: “I have a hard time believing that the food reward system in the brain is a dominant site of metabolic damage.”

What if you look at the food reward system as a dominant *source* of metabolic damage?

I find this idea — dysregulated appetite -> overeating of SAD foods/toxins -> gut/liver injury -> metabolic syndrome — compelling.

BTW, I’m not sure how you’re making the leap that obesity has to exist before food reward is a factor. I know people get stressed out when you use the a-word (addiction) with food, but I think Gabor Mate makes a plausible case for how brain development in infant/toddlers can predispose them to reward issues.

All of this said, I’m with you that the implication that you need to eat bland food is perhaps overkill. When we eat whole foods, our food reward system can work the way it’s intended. And it certainly makes sense to continue to eat spices that traditional cultures have been using for thousands of years!

One more thing. I think you’re missing an important point re food reward. It’s true that fat+starch is high reward, but there’s a huge difference between the PHD idea of this rewarding combo, say rice plus coconut oil, and a SAD food like Doritos, whose PUFAs may be affecting the endocannabinoid system (see Emily Dean’s posts on that) and whose wheat and sugar may be pinging our opioid receptors big-time.

Paul,

I’m glad you have offered your take on this issue.

I think its an interesting question whether you should eat high reward paleo foods like PHD or low reward paleo foods like Stephan. If we accept the premise that the brain’s reward system gets “confused” by neolithic or industrial foods that were not encountered during the Paleolithic, we might also accept the idea that a similar problem might occur with combinations of paleo foods that are evolutionarily novel. For example, even if starch and fat are not overly stimulating to the reward system individually, they might be quite stimulating in combination. I cannot think of any benefit to eating starch and fat at the same time, so my guess is that the higher reward value of this combination is a supernormal stimulus that confuses the brain into eating too much as opposed to giving it accurate signals about what to eat. So I would guess that combining paleo foods to be as rewarding as possible, while still far less rewarding and problematic than industrial foods, may still be rewarding enough to confuse the brain into making energy balance errors. Or maybe not.

On the other hand, low reward diets are destined to fail if the dieter has a “reward set point” that is not down regulated by eating bland food. In other words, if we start eating bland foods to lose weight, our need for food reward might stay the same even as our need for calories decreases. In other words, you might end up starving for reward even if you are not starving for calories. Maybe you will end up trading one addiction for another. I recall developing a major chocolate addiction when I went Loren Cordain style paleo a few years ago. Interesting issues. I am looking forward to more debate on this and some self experiments with palatability.

Perhaps the least “confusing” type of diet would be a mono diet. Or perhaps just mono meals. What strikes me about all these traditional cultures being discussed in the context of food reward is that single foods would often make up the majority of their calories for long periods of time. Is the brain adapted to handle the myriad of flavors we simultaneously bombard it with whether they are “paleo” or modern?

It’s great to hear the PHD take on such a fascinating and new to me subject as food reward. Food reward is just one more piece to the puzzle. The concept helps to put in perspective how other weight loss diets can “work” and have fans support them even if its temporary or unhealthy. Followers of the PHD don’t have to defend PHD and claim no other diet but PHD can possibly work to lose weight as many are prone to in the diet world for their diet. Instead, we can see the PHD as better just in a larger context. Wow, alot to digest in this article. 🙂

Fascinating! I’m glad to see you exploring this topic in depth. The idea that obesity is a different condition than simply being fat has many interesting implications, and I’m looking forward to seeing you explore them.

Continuing: My opinion is that blaming “food reward” for obesity is like blaming “alcohol reward” for alcoholism: it’s just restating the problem.

The more important question is: what causes foods to be rewarding? My theory is laid out here, in The Grand Unified Theory of Snack Appeal, and I believe it agrees with yours: the problem isn’t that certain foods are rewarding, the problem is that the reward has been divorced from the nutrition that historically accompanied it in evolutionary time, and which caused us to develop those tastes in the first place.

(There is also the serotonin-boosting effect of simple carbs eaten in isolation, with which I’m sure you’re familiar.)

I absolutely agree with your solution, which is not to eat bland, unappetizing food: the solution is to eat whole, nourishing foods that contain the nutrients which have always accompanied their delicious taste!

Finally, I’m not sure that Stephan’s contention that Paleolithic diets were monotonous is supported by the evidence, which shows over 100 types of plant residue in one cave, or over 20 types in the gut of a frozen corpse. I think monotony is more the result of adaptation to severe competition for overpopulated, marginal lands in a depleted post-Quaternary-extinction ecosystem…but I’m open to correction here.

JS

PS: To that end, I’m suspicious of nut butters and nut flours, which seem to me to be the equivalent of fruit juice: an evolutionarily novel refinement that allows easy consumption of calories. Anyone ever tried to shell enough almonds to make almond butter?

Hi Paul,

I’ve enjoyed your take on food reward. If you haven’t read it yet, I highly recommend The End of Overeating by former FDA Commissioner David Kessler. It’s all about food reward. He’s got some things obviously wrong, but he likely gets food reward right. It’s not just about salt intake on it’s own. It’s about salt intake with fat and sugars together. He’s got a few chapters that deal with how the fast food industry (and places like Friday’s and Chili’s) design their food. Water typically mostly removed from the meat, it’s pre-fried (replacing the water with fats), preserved, frozen, and then shipped to the stores where it’s fried again before serving with a sugar rich sauce. He talks about how the meal is basically fat on top of fat on top of salt on top of salt on top of sugar. Etc. It’s super dense and hyperstimulates the food reward centers. There’s more to it than that. You really should read it. Thanks for the post.

@Todd: I am not sure that Carbs+Fat combination is novel to humans. We after all evolved in Africa, and possibly very near to those coconut trees. Coconuts are natural desserts, they are fatty and carby at the same time and taste slightly sweet. I find that I like the taste of tender coconut a lot, but I am not able to eat too much of it. It is a very good snack for me when I am travelling, very filling. And it is available very easily locally.

Hi Paul,

Is Stephan’s diet of 50% carbs considered excessive and harmful wrt PHD? It seems that would be well above the recommended upper plateau 600 cal carbs.

Thanks,

Mark

“I think our evolved preference for tasty foods including starches, fat, salt, and other “high reward” flavors indicates they are healthy, and therefore that a diet rich in such foods is most likely to cure metabolic damage.”

No flavour seems to be more rewarding than the sweet flavour. Wouldn’t your argument lead to the conclusion that consumption of naturally sweet foods should be healthy?

@Todd, I think the biggest problem with low reward diets is that they are very, very difficult to do in a modern environment. On a desert island, I’d be fine with boring food all day, every day. But when I’m bombarded with images of highly palatable industrial food (or presented with it at work or at family gatherings) it requires either conviction (ref: Kurt Harris’ candy cigarettes) or super-human willpower.

For that reason, I’m wondering if Tim Ferriss may be on to something with his Slow Carb diet. Eat routine for six days, and then ping the reward system on one. He thinks it works because it keeps the thyroid functioning. But maybe it works because it keeps folks compliant longer than they would be on a more restrictive diet?

@J. Stanton, I don’t know that it is only restating the problem to implicate food reward for obesity. The author of the video series at yourbrainonporn.com makes a good case that Stephan’s “professionally designed industrial foods” exploit our natural reward system.

The implication of this connection as he suggests is that you need to “reboot” (avoid the stimulus) and “rewire” (restore normal reward functioning).

To my mind, this doesn’t imply eating bland food, but it does mean avoiding (or eating sparingly) modern foods a la Kessler/End of Overeating.

Beth,

I agree, the addiction to rewarding food may be one those types of addictions that are totally easy to overcome provided you aren’t in the context that provokes the craving. Many people would have no problem at all quitting smoking or drinking on a desert island, but it would be absolutely impossible for them in a bar. Same with me and the internet! But heroin withdrawal is tough no matter where you are.

Todd, the good news is that withdrawal is generally short-lived! But the problem for most of us with those sensitivities is relapse. Me, I’m on the far end of the bell curve (for me, it’s closer to addiction than not — I consider myself the poster child for BED).

In the past, my downfall has been traveling. This past trip over Memorial Day, I experimented by ensuring that I didn’t string ultra-high reward meals together. So for each meal I ate out, I followed it by at least one low-reward meal … more if the high reward meal had the big three (sugar, veggie oils, and wheat).

I’m pretty pleased with how it came out food-wise. Will be interesting to see how it played out on the scale tomorrow ;).

I’m a believer in super stimuli foods changing eating patterns and appetite.

In our home, when we make GF muffins for a treat, they do. not. last. GF pizza? Same.

We all love the chili we make, and the beef stew, and the chicken coconut soup….but none of these foods fire up our brains to go and get MORE like having baked goods or pizza in the house.

What always surprises me is how these foods only taste good while I’m eating them, but the do not give lasting satisfaction. After one muffin, I’m ready for another!

There must be something about the instant reward of finger food, too. No waiting!

Our strategy so far has been to recognize our response to these foods, and save them for special treats. For the most part, it’s best to keep them out of the house.

I do wonder how my kids will manage when mom is not cooking for them any longer, and they are increasingly busy with school and work.

Michelle, this past week my neurofeedback doc mentioned that there’s apparently a well-known saying re these ultra high reward foods: “one is too many, a dozen is not enough.” Word!

Hi Beth,

My base view is that the source of damage is elsewhere – chronic infections in many cases, food toxicity-malnutrition in many, the two probably interact – and that the metabolic derangements lead to distortion of the food reward system.

But I’m open to the idea that the food reward system is somewhat neuroplastic and that when eating high-reward foods fails to nourish – contrary to evolved expectations – the brain alters to try to make sense of it, and either pushes much higher reward (“thinking” the problem was insufficient response to reward, and it needs to induce hyper-reward to successfully alter behavior) or becomes distorted, attaching reward to the wrong foods.

If this happens, then I could see malnutrition on a high-reward diet leading to the system going haywire.

I am a newcomer to the biology of reward, addiction, and the brain generally, so this aspect of obesity is something I have to learn about. It would help me to see a review of how the part of the brain hosting the food reward system is altered in the obese compared to normal people.

Possible pathways that begin with developmental brain errors leading to obesity is interesting. There is some evidence that mothers can pass obesity to their offspring through epigenetic regulation. But this is more a case where metabolic damage begins in the mother and then affects the (infant) brain. It doesn’t show what got the whole process rolling.

And I agree, the endocannibinoid role is a very important finding and may be the missing piece that makes the food reward pathway make sense. One thing I’m missing from Stephan so far is a discussion of biological mechanisms that make sense of these complex food reward observations.

Hi Todd,

I don’t think there’s any harm in eating starch+fat together. I think the main issue for preserving a healthy food reward system is to have high food reward meals be followed by a well-nourished and healthy body.

I think the brain gets signals from the body regarding nutrient status, health, etc., and when a high reward meal is followed malnutrition and ill health, then the brain changes. That’s when the food reward system may go haywire.

But if your diet is healthy, I think enhanced food reward is a good thing, not a bad thing. It is just reinforcement of a good lifestyle and makes for a happier, more enjoyable life.

Your idea that low reward foods may promote addictive behavior is very interesting. I’d like to hear a specialist comment on that.

Hi Monte,

I think “mono” diets are rarely healthy. As Stephan said about the all-potato diet, it’s probably the healthiest mono diet there is, but far from optimal.

For your question, see my response to Todd.

Hi Jaybird,

It’s good to have fans! Thanks.

Hi Paul.

Thank you for your great site and this post, however I’m confused by these two statements:

“I think our evolved preference for tasty foods including starches, fat, salt, and other ‘high reward’ flavors indicates they are healthy, and therefore that a diet rich in such foods is most likely to cure metabolic damage.

I think it is essential to stay away from toxic, malnourishing foods made from wheat, fructose sugars, omega-6 oils, and bioactive compounds like MSG; and instead to eat foods that accord with our evolutionary history.”

My question:

How can our evolved preference for tasty foods indicate they are healthy when that evolved preference includes fructose sugars and things made of wheat, which are toxic and malnourishing?

Hi JS,

I read your post – outstanding! – and intended to mention it but the post got too long and too late. I’ll cite it on Saturday.

Thanks for mentioning us!

I fully agree: it’s reward without nutrition that is disastrous.

I also agree with you that Paleo diets were not boring, at least not all the time. I think a common lifeway would have been to have some stay at camp preparing food while others hunted/gathered, and to share a feast in late afternoon. If you only have one major meal, you can spend time preparing complex flavors. They had access to a wide variety of foods as you say. They would eat all parts of animals, which by itself adds a great deal of variety. More than 300 plant species were exploited in some locations; a modern supermarket stocks more like 50, and most people eat well below that.

We don’t know the Julia Childs and Gordon Ramseys of the Paleolithic, but I am sure they had their culinary specialists.

Hi Poisonguy,

Thanks, I haven’t read it but your recommendation may get me there.

Hi MarkES,

Well, I think fewer carbs is optimal but I think there’s very little harm in going above our carb range, if the carbs are composed of safe starches.

I am mainly influenced by evolutionary evidence – breast milk and most animal diets are low carb, suggesting selection for low carb eating.

Another factor is practical: there aren’t a huge number of naturally safe starches; a high carb diet based on rice, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and taro – the principle safe starches in our home – would get boring fast. We don’t have time for the soaking/sprouting/fermenting Stephan does, and I think most don’t. I think taking food should be highly enjoyable. Our recommended ratios work out to about equal weights of starches and animal foods, which I think is not overly animal-heavy.

Hi Mirrorball,

I do think some sweetness is healthy. We oppose zero-carb eating and don’t mind fruit and glucose-based sweeteners as sources of carbs.

I don’t think sweetness is especially rewarding by itself. Seth Roberts recommends sugar water to dis-associate calories from flavor in the Shangri-La Diet. Fructose in fruit comes with a large mass of plant matter that takes time to digest and discourages overconsumption. It’s the hyperstimulation of fructose-without-mass accompanied by fat (and perhaps salt) that produces excessive reward.

We recommend excluding added fructose sugars from the diet – thus our recommendation of rice syrup as a sweetener – but the more modest fructose in fruit should be fine, especially on a low-carb diet which allows better disposal of fructose.

Hi Todd,

My Internet addiction persists even when I’m away from it. A desert island would induce delirium tremens.

Hi Michelle,

Better not try Mario’s Brazilian cheese puffs: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=1151.

Hi Erik,

I think wheat and fructose were not major parts of the Paleolithic diet. I think on low-carb diets, which were the norm (see http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=2168), a little fructose (of the amounts found in fruit) may be beneficial; it is certainly not very toxic on a low-carb, low-PUFA diet. I think wheat and fructose never reached levels in the diet that would have perturbed the selection of the food reward system.

Paul, re your question about possible mechanisms, to start, I’d check out these resources at Yale’s Rudd Center: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/what_we_do.aspx?id=263

For a particularly recent paper, check out their Neural Correlates of Food Addiction: http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/resources/upload/docs/what/addiction/NeuralCorrelatesFoodAddiction_AGP_4.11.pdf

But honestly, I totally recommend the six part video series at yourbrainonporn: http://yourbrainonporn.com/your-brain-on-porn-series

It’s probably too lay for you (it’s developed for porn addicts), but the author lays out a good case showing how for mahy of us, our lizard brains reward systems aren’t up to the task of the modern environment.

At first glance, food reward as an explanation for obesity sounds like a doctor telling you the pain in your back is all in your head. Telling an obese person their fat because they find bad foods pleasurable and eat them too much just makes them more frustrated. That’s essentially what the medical establishment is saying, in my opinion, when they say “a calorie is a calorie.” That’s why Taubes has struck a chord with many people pointing to hormones and biological factors. This is why Stephan’s food reward brought out some anger in some commenters at his blog for seemingly pointing back to will power, lazy, and sloth arguments or “it’s all in your head.” Paul does a great job here balancing things out and incorporating it all like there’s one big feedback loop happening. The neolithic villains are manipulating the brain’s food reward system and then screwing up the rest of our biology, which drives the brain more to seek a false pleasure. Although, I think maybe Stephan Guyenet has hinted that his “food reward” concept somehow incorporates this larger explanation as well.

I skimmed through the post, will read it in depth later today. But I’d like to point out that Reward Foods can be cultural. For instance in Taiwan and Japan, pickled or dried ume are eaten as snacks. These ume snacks are lip-puckeringly sour, and are also either salty or salty/ touch of sweet. Anyways, they’re very low calorie snacks, I doubt anyone would gain weight consuming them even if they’re eating copious amounts.

Some traditional Asian culinary cultures have aversions to overly-sweetened foods. Both of my surviving grandparents in Taiwan are 100+ years of age, they don’t eat sweets on a regular basis unless you count small servings of fruit which they grow themselves as “sweets”. When they do eat desserts, it’s usually consumed as part of celebratory feasts or when guests bring them as gifts. Even theses desserts are less sweet and lower in fat than Western desserts. Fat + sugar= disaster.

Anyways, the traditional snacks that my grandparents consume are Japanese style snacks…Taiwanese snacks are heavily influenced by Japan because it was a somewhat “willing” Japanese colony. Both my grandparents pretty much still live/ eat like the Japanese. So snacks like mochi (glutinous rice, sweetened adzuki bean or chestnut paste filling) or small cakes (rice/ wheat flour, sugar, little or no fat), or senbei (rice crackers) etc…are their “food rewards”.

Hey Paul,

I’ve read this post a few times now, and I really like it, as it has helped me organize some of my own thoughts on the subject based on what I’ve read. I think that Stephan did his readership a disservice by mentioning “palatability” at all, because people seem to be extremely confused about “reward” and “taste” as being two totally separate concepts that have very little to do with each other.

I suspect that you are right about a number of things in this post. High reward foods are good, as the reward center has evolved to seek out healthy foods. But we need to make a distinction between highly rewarding foods and “hyper-rewarding” foods. I may be wrong in speculating on this, but I imagine that there are independent measurements of reward value based on measurements of brain activity in a specific area, whether they be imaging or literally plugging electrodes into animal brains and measuring output. Food companies optimize processed food, either directly or indirectly, to maximize this reward value, and in doing so have created foods that are completely outside of our evolutionary experience and as a result cause chemical changes in the brain that upregulate the set point. I asked Stephan about the biochemical mechanisms by which food reward would upregulate the set point, and he responded here:http://wholehealthsource.blogspot.com/2011/05/healthy-skeptic-podcast-and-reader.html?showComment=1305563086428#c6326811724798000292.

It sounds to me like the reason that Stephan is calling food reward a dominant factor is because it may be the only thing that can upregulate the leptin set point. That’s not to say that other factors can’t contribute to obesity, particularly by interfering with the signaling mechanism (leptin resistance among other things), but changes to the set point will generally have a greater effect. Of course, hitting both at the same time may have the synergistic effect. It’s also possible that wheat is uniquely bad because it both inflames the body and interacts with opiate receptors in the gut and brain.

I suspect that all of these other systems that you refer to in this post are inducing weight change by interfering with the action of the signaling, not by changing the set point. My operating hypothesis is that the chronic inflammation response releases some cascade of hormones/enzymes that inadvertently bind to leptin receptors in the brain, or somehow otherwise effect this signaling, but there may be other changes that can happen downstream of leptin signaling that also cause problems. Because so many causes can stimulate an inflammation response, there could be a number of factors from gut flora to infection to lack of sleep to plant toxins that can have a similar effect on fat mass.

A few years ago I used the Shangri-La Diet (SLD) with some success. I drifted away from the SLD the more I understood about nutrition. Once one begins to understand the issues with excess Omega-6, the less one wants to slam back 4 Tablespoons of Extra Light Olive Oil every day. (Or, when looking at the impact of fructose to the liver, drink 400 calories of sugar water.)

So, in theory, I agree with you that one should strive to improve health more than try various ‘hacks’. I know I could blend together a bland drink consisting of soy protein powder, safflower oil, fructose, and wheat flour, and lose weight by only drinking that concoction, but I also know that the overall long-term impact to my health would be detrimental.

Since quitting SLD techniques, I have migrated to paleo. And, having determined that the PHD makes the best case for optimal nutrition, it is the plan I follow. And yet I continue to carry 20 pounds of excess visceral fat.

I agree that perhaps I have not followed the PHD for a long enough time for the PHD to take effect. And yet, I am an impatient American. I want results. That visceral fat not only looks ugly, but the same logical mind which knows that the PHD is providing optimal nutrition, also knows that the visceral fat must be causing harm due to inflammation.

I have two questions.

First question . . . . I wonder if there are ‘hacks’ out there which will solve this excess visceral fat issue? Hacks which can be applied on top of the PHD? Will 16-hour fasts turn on autophagy and improve hormone signaling/sensitivity? Alternatively, will eating nutritious bland food, for some meals, somehow encourage weight loss? (As described by Stephen in the experiment with the food-dispensing machine, and the experiments described in the Bland Food section of Seth’s paper at http://sethroberts.net/about/whatmakesfoodfattening.pdf).

Second question . . . given the argument that obesity could be caused by damage to any number of organs . . . of those listed (liver, adipose tissue, brain, skeletal muscle, gut and gut flora, endocrine), what lab tests can and should be ordered by somebody in my condition to determine what is broken? And what cannot be measured at this point in time and yet you wish could be measured?

Beth wrote:

“Michelle, this past week my neurofeedback doc mentioned that there’s apparently a well-known saying re these ultra high reward foods: “one is too many, a dozen is not enough.” Word!”

I love that, Beth, thanks!

Paul wrote:

“Better not try Mario’s Brazilian cheese puffs: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=1151.”

Oh, you KNOW I skipped that recipe on purpose!

Hi Jana,

Very good point. My wife, nephew and niece (who live with us) were raised in Asia and their tastes are quite different from mine. They find American food excessively sweet, yet enjoy kale-type vegetables that I find unpleasantly bitter.

Is this adaptation, or biology? Regardless, the Asian way of eating is much healthier. Not surprisingly, obesity rates are lower and lifespans longer.

Hi Geoff,

I like your theory and basically agree with it. The mechanisms are a bit more complicated – toxins don’t bind to leptin receptors, the mechanisms are indirect – but I think big picture wise you’re basically right.

The food reward system is certainly not the only thing that can upregulate the leptin setpoint. Stephan himself says that inflammation can do it. That means a wide array of infections and toxins can do it.

Hi R.K.,

The Shangri-La diet is not inconsistent with our diet. You can choose PHD-compliant foods to achieve the same flavor-calorie associations that Seth uses unhealthy foods for.

I now recommend that people trying to lose weight do intermittent fasting (16 hour fast / 8 hour feeding window) daily and take a spoonful or two of coconut oil during the fast. Coconut oil is ketogenic and eases the stress of the fast for those with glucose regulation issues, but it also implements one of Seth’s Shangri-La Diet protocols.

I hinted at this in my post, and will expand on it in the future, but I think chronic infections are significant causes of extra weight. Inflammation in adipose tissue and inflammation in the liver – both normally caused by infections or die-off products of pathogens – can cause obesity and/or weight gain.

So curing obesity can take as long as it takes to cure chronic infections, which can be several years even when you know the pathogen and receive antibiotic treatment.

In terms of lab tests, I would do things that look for infections and gut health. You can check the feces for pathogens, for instance, and then try to fix the gut flora. However, it is difficult because most chronic infections are invisible to contemporary medicine. The standard tests for infection look for acute responses that don’t occur with chronic infections.

I will be working on this, but for now I think intermittent fasting is curative for many chronic infections that are likely to be involved in obesity, so that is what I would recommend as a starting point. Next would be checking out the gut and improving the composition of gut flora.

Another type of hack is to try to migrate fat from adipose tissue to muscle, by doing strenuous resistance exercise 1-2x per week. Aerobic exercise like running is also good, it improves vascular health which may be involved (see the Rupnick results above). Taking leucine / BCAAs and creatine may help with muscle synthesis. If you maintain calorie restriction then muscle synthesis will come at the expense of fat tissue.

Best, Paul

I think everyone has a tendency to “overeat” when

the food is tasty! Yet, everyone isn’t obese.

I was a skinny, malnourished looking kid. When I was

16 my parents moved us to Iran. (1978-1979)

On arrival I was told to avoid the water. I did.

However, I didn’t think to avoid ice cubes. Not funny. I soon became very ill. I truly thought

I would die. My already thin body became skin

and bones. Thankfully I recovered.

Our new environment was a challenge for me. I was a former outside country girl. Now, I was confined to a small home. The Iranians didn’t appreciate the way I dressed, and would throw rocks at me. My Dad insisted I stay home.

In an effort to cheer me up, my Mom started baking

lots of delicious treats. I was content to indulge myself for an entire summer. I gained about 34 pounds in less than 3 months.

Once school started, I couldn’t wear any of my clothes. I jumped from a size 3/5 to an 11! I started school wearing my older brothers clothes. It wasn’t easy to buy appropriate clothing in Iran.

I should add, I am only 5’3 1/2′

I was disgusted with my weight. I joined every athletic program. I took two P.E. classes. I began fasting all day until dinner. I could not lose the weight.

Once we moved back to the states, I started getting out, jogging, and continued taking two P.E. classes. One of those classes was track. I took up smoking. I continued to fast until dinner. I never lost a pound.

After graduation I joined the Army Reserves. I thought for certain Basic Training would get the weight off. Nope. Not one pound. Trust me, no reward foods there. They didn’t even give you proper time to eat. Many times I had to dump most of my meal in the trash.

I married. Got pregnant. Suffered morning sickness. The morning sickness, was “all day”

sickness. I lost 15 pounds my first trimester.

When my baby was born I weighted less than the day

I became pregnant.

I never regained the weight. I had two other children. Same scenario.

I am now 49. I haven’t regained the weight. I eat more now than ever. Yet, age is catching up with me. My body wants to redistribute my fat to my mid- section. I work on this daily. 🙂

So, I feel deeply for the obese. It isn’t all about stuffing yourself. It isn’t about being a sloth.

I do think infections, and toxins are a huge factor.

I believe this is what happened to me. I think the toxins of all the baked “wheat” goodies, on top of the horrid gastrointestinal bug, was the main culprit. I know being sedentary played a roll too. However, I am more sedentary now. Plus, I allow myself to indulge in gluten free goodies made with safe starches.

Hi Betty,

Thanks for your story. I also think infections and toxins are usually the cause. I’m glad to hear you recovered and fascinated that it occurred during pregnancy. Often autoimmune conditions disappear during pregnancy – I wonder if you had infection-induced autoimmunity?

Best, Paul

Paul,

I too was amazed that I recovered during pregnancy.

I do believe autoimmune is a real probability! As you may remember, I have my share of autoimmune troubles.

When reading both this & Stephan’s original post today, I found myself thinking about my lifetime favorite snack, Wheat Thins.

Of course, I haven’t eaten Wheat Thins in about a year now, given what I’ve learned from Gary Taubes’ book, Stephan’s blog, and the PHD book.

Even thinking of Wheat Thins caused me to actually crave this “food”!! I found myself salivating and getting hungry specifically for these, even though I just ate a perfectly awesome nutritious PHD lunch and am not actually hungry or in need of any food.

Out of curiosity, I looked up the ingredients. Wheat flour, soybean oil, and sugar are the first three ingredients. Holy cow.

Thanks for this great post & I love reading all the comments. I am impressed with so many people making awesome contributions to the conversation.

Paul:

I link your articles frequently. You’re on my shortlist of people who are pushing the boundaries of dietary knowledge, and I’m honored that you consider me worth reading and linking.

Beth:

What I’m saying is that even if we define “food reward” very specifically, as something that lights up specific set of reward circuits in the brain, we still haven’t said anything interesting. It’s like defining a car crash as “two vehicles attempting to occupy the same part of spacetime”.

I’m reminded of Dave Dixon’s classic essay On Taubes And Toilets. Unless we talk about what specific characteristics make some foods rewarding and others not rewarding, “food reward” is not a helpful concept.

Right now it seems like everyone’s just assuming they know what’s rewarding and what isn’t: fast food is rewarding, bland food isn’t. But then I should be able to consume a lot more calories at Taco Bell (spicy, tasty, deliberately engineered) than I can from drinking half-and-half (bland), and that’s simply not the case.

To me it’s a question of reward vs. satiation. If a food is rewarding AND satiating, that’s fine. It’s the foods that are rewarding but not satiating that we need to avoid. And identifying them is the subject of my article I linked above (which I can’t link again, as articles with 2+ links tend to get stuck in spam filters).

Poisonguy:

“It’s not just about salt intake on it’s own. It’s about salt intake with fat and sugars together.”

Most importantly, it’s about those two plus the absence of the complete protein which always accompanied fat in evolutionary time (e.g. meat). As I state in my article, it all comes back to the ability of modern technology to separate the tastebud-stimulating substances from the nutrition they’ve always accompanied, and to concentrate them far beyond their natural occurrence (HFCS, MSG, etc.)

JS

Paul, was catching up on the comments over on Stephan’s and found this link for an older paper on brain dopamine and obesity (PDF). Googling Volkow and obesity turns up lots of others as well.

I agree that while Food Reward may be contributory to the obesity epidemic, it may not be the one, dominant factor. As I understand it after reading the post, paradoxical FR envelops brain chemistry, evolutionary preferences, and behavioral modalities into somewhat uncontrolled i.e. subconscious addictions to unhealthy foods.

Yet, as Paul pointed out, “obesity-causing and obesity-curing diets may have similar food reward.” That would explain why my 100+ year-old, slim, physically active grandfather with his lifetime diet of pork (all parts of the pig), fish, eggs fried in lard, and rice/ vegetables/ yams/ small amount of fresh tofu, is healthier than his 40 year-old overweight grandson already afflicted with pre-Type II Diabetes and gout. Guess what type of food my cousin, an orthopedic surgeon in Taipei, eats? That’s right, like most MDs he doesn’t know jack about nutrition, and is on SAD albeit Taiwanese-style, which means lots of wheat-based foods like meat-filled buns/ dumplings/ buttery-sweetened breads and cakes, sugar/ fructose-loaded fruit smoothies, and meats or tofu snacks fried or stir-fried in “healthy” vegetable oil.

I also like the distinction of disease of obesity vs. condition of being fat. Theoretically, a person who yo-yo diets can be on an endless loop between the two states, correct? If weight gains only happens with metabolic damage, what is the threshold for that to occur?

I would think our bodies are designed to self-repair via innate homeostasis if it’s only one organ, like skeletal muscle for example, that’s afflicted? Perhaps the skewed FR mechanism interfere with this process? The leptin-impaired rats certainly gives one much to ponder. I guess this is what researchers hoping for a gene-manipulating, magic diet pill are basing much of their hypothesis upon.

Hi, Paul, a quick follow-up to your recommendation for intermittent fasting. I have been attempting to migrate to 16-hour fasts over the past several months, and have had some small success (8 times in 70 days). I keep re-reading what you have written about fasting and ketogenic diets. Several quick questions (before you write a whole post about it):

I have tried to chug back refined coconut oil per SLD techniques, yet various internal systems hate it. My hedonistic system loathes the experience and my gut hates the bolus of oil. Based upon what you have written, is it possible to:

a) add some coconut oil to my morning tea in order to extend the true fast from, say, 13 hours (which is fairly easy now for me) to the 16 hours?

b) also add some 100% cream to that tea (which also has the coconut oil)?

c) is drinking coconut milk(*) another way to extend a fast . . . in other words, drink about 300 calories worth of coconut milk at the 13th hour?

(*) note: I dislike the taste of canned coconut milk, so I make my own using coconut flakes purchased from Whole Foods which are then put in a blender with water, liquified, and drained and pressed through a colander.

Many thanks for your time and interest.

Paul, R.K.

I remember reading about the Shangri-La Diet and thinking that if Seth’s hypothesis were correct, then taking tasty non-calories should work as well as tasteless calories. If this were the case then I imagine that drinks like coffee or tea without any sugar or fat would do the trick, or am I missing something?

Love the book, by the way. It’s in a friend’s keeping at the moment as she wanted to take a look before I left the country, but it’s definitely going to get the cover-to-cover treatment on the plane.

Hi Anna,

Great story. There is something to unhealthy food and addiction. It’s hard to fathom it though. J Stanton has a good theory.

Hi JS,

We allow up to 4 links.

Hi Jana,

I don’t think yo-yo dieters are curing their obesity when they lose weight. They are still obese in a (temporarily) thin body. But the thin state might be less healthy for them than the fat state that the brain is defending.

Metabolic damage can exist without weight gain. On weight plateaus, overweight people still have metabolic damage. If the damage were cured, they would rapidly return to normal weight.

Hi R.K.,

If you don’t like coconut oil, try MCT oil. It’s tasteless and more like water in its consistency. Much easier to swallow I think.

You could also mix in some protein powder with it if you wanted.

Coconut milk is fine, as is putting coconut milk or oil in your tea.

I don’t think you need 300 calories, although that’s fine. 100-200 calories is probably enough.

Cream in coffee … I’d have to hear Seth’s opinion whether that would assist weight loss. It might have the very flavor-calorie associations that he’s trying to eliminate.

Hi Andrea,

I agree, tasty non-calories should be as good as tasteless calories. But don’t ask me, this food reward psychology / biology still mystifies me!

Best, Paul

@Andrea:

I suspect you’re considering the SLD tactic known as CFF (calorie-free flavor), explained below.

But before describing CFF, let me first point you at a different perspective of flavor-control diets, written by Todd Becker at http://gettingstronger.org/2010/02/flavor-control-diets/ .

The key CFF analysis comes from the SLD forum in a post by Seth, who starts by quoting a user named Trina:

HUSBAND: Started Oct./06, with 15 lbs. to lose. Always drinks Kool-Aid (reduced sugar) with and between meals. AS? Never hungry; cravings gone, gone, gone; often misses meals (unheard of for him before SLD—had to have breakfast upon arising, now cannot even eat til noon); happily considers SLD part of his life; never worries about weight now, just knows that is is slowly decreasing and is confident it will stay that way. (Grrrrr!)

Seth says:

Yeah, that would be the way to do it. You can think of the Kool-Aid as soaking up some of the dangerous (i.e., fattening) calorie signals generated by the meal and then getting rid of their dangerous byproduct — a flavor-calorie association — by having the Kool-Aid between meals without calories.

Dr Briffa has recently done an interesting post entitled ‘More evidence links MSG with obesity’.

here’s the link;

http://www.drbriffa.com/2011/06/01/more-evidence-links-msg-with-obesity/

do the lycopene supplements have lectins in like tomatoes?was looking at Cordains MS youtube lecture and saw the down on tomatoes,but Lycopene seems to be a good antioxident.so how to get it without tomatoes.

Susceptibility to the “hit” of food reward can be variable, even in the same individual. There are other behavioural/hormonal factors in play. I know that when I am at work during the week – mildly sleep deprived and stuck at my desk and often a bit bored, I find it very hard to resist overeating. When I am at home at the weekend, having slept until I wake naturally and able to move around and do what I want, my appetite suits my activity levels. I still seek out food for pleasure, but it seems to be in balance.

“The level of activation of PPAR-gamma affects the amount of leptin released per unit fat mass. PPAR-gamma deficiency leads to hypersecretion of leptin from adipocytes;”

I searched for information on how to initiate the PPARv deficiency, but was unsuccessful. Anyone out there know of a hack for that?

Never mind. Changed my search and found this:

“Fasting (12–48h) was associated with an 80% fall in PPARg2 and a 50%fall in PPARg1 mRNA levels in adipose tissue. Western blot analysis demonstrated a marked effect of fasting to reduce PPARg protein levels in adipose tissue. Similar effects of fasting on PPARg

mRNAs were noted in all three models of obesity.”

I forgot to say that my inquiry was on behalf of my post-menopausal wife.

Sounds like the IF we’re doing with PHD, if supplemented by occasionally longer fasts, will yet succeed.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC507341/pdf/972553.pdf

Hi chris,

Personally I’m not too worried about eating tomatoes. Tomato lectin hasn’t been shown to cause any pathology yet, so in moderation it should be OK.

However, there are lycopene supplements available if you’re worried.

Hi Kate,

Yes, it’s really a “reward” system not a “food reward” system and Todd Hargrove has been making the interesting point that non-food and food sources of reward can be substitutes. Unrewarding work could require compensation in the form of rewarding food!

Hi Jim,

Thanks for doing the research!

It’s a rather complex subject and the topic of future blog posts … but I think intermittent fasting is a good strategy in obesity.

Best, Paul

Paul,

Thanks for this thought provoking post. I think you are really moving the ball down the field on this and other health issues of great import to many folks.

I’m personally interested in the topic of obesity, because friends in my age cohort and family members sometimes ask me for advice on losing weight. Why? I suppose because at 52 I am not overweight, have decent muscle tone, and have relatively unwrinkled skin. As I have noted elsewhere on this blog, I have had my health issues over the years, but gaining weight has not been one of them. Apart from the “freshmen 15” I gained in college, and then subsequently lost on my self devised diet of no desserts and no fried potatoes, my weight has stayed very constant over the years.

I used to think this was a simple issue. My advice to people was portion control and avoiding desserts. The latter was colored by my college experience. By not eating desserts for a couple years, and believe I desensitized myself to the enjoyment of sweet tastes. While I have eaten desserts in the succeeding years, it has been relatively infrequently, and they always taste too sweet to me. So I thought everyone could lose their tastes for sweets and in the process avoid a lot of empty calories.

Well, not surprisingly, few people had success with my advice. Later, after experimenting with low carb diets for my headaches, I thought this was the answer. In my own experience, going low carb resulted in a dramatic reduction of my carb (ie, bread and pasta cravings). I thought this would work for everybody. Just change what you eat and the dysfunctional cravings will melt away. Well, not so fast. Some people I know have had success with this approach. The best candidates for weight loss success on a paleo style diet in my observation are middle aged guys with guts. Women, not so much. Some people just shift their cravings to other foods like nuts or dairy.

What all this has taught me is their are no easy answers for people struggling to lose weight. And I’m not even talking about folks who are clinically obsese. Just 15-30 extra pounds can be very difficult to shed. If anybody asks for advice these days I counsel the PHD and PATIENCE! I do believe that metabolic damage done by poor nutrition is the root cause of most excess weight. I imagine the damage is not uniform, ie, different organs and systems sustain different levels and types of damage depending on the particular toxins favored by the person and their genetic predispositions. I did pretty well over the years avoiding fructose, but I didn’t eat enough healthy fats, and I consumed a lot of whole grain wheat products. Other people have had different eating patterns, say less wheat but more sugar. Or more foods fried in vegetable oils. Added to the metabolic damage are the emotional issues surrounding food and self image, and I suspect these issues are in turn influenced and abetted by the metabolic damage people have sustained.

No easy answers for sure, but I think the work you and others are currently engaged in is fascinating and finally offering real hope to many many people who struggle with obesity and excess weight.