In my reply to Jimmy Moore’s safe starches symposium (see Jimmy Moore’s seminar on “safe starches”: My reply, Oct 12), I didn’t quite have time to fully address the issue of hyperglycemic toxicity.

As J Stanton commented, it would have been good to note that we recommend consuming “safe starches” as parts of meals, not as isolated snacks, and to discuss how meal design mitigates risk of hyperglycemic toxicity:

I’ve written entire articles on the fact that fat content is the primary driver of glycemic index. It’s silly to demonize white potatoes due to high GI when a couple pats of butter – or simply consuming it as part of a PHD-compliant high-fat meal – will drop it far more than substituting a sweet potato.

I thought I’d delve into the factors affecting blood glucose response to meals, and how to minimize the rise in blood sugar. It’s a topic of general interest, since hyperglycemia might have a mild detrimental health effect in nearly everyone; but of special importance to diabetics, since controlling blood sugar is so crucial to their health.

Glycemic Index of Safe Starches

The glycemic index (GI) is “defined as the area under the two hour blood glucose response curve (AUC) following the ingestion of a fixed portion of carbohydrate (usually 50 g).” Pure glucose in water is used as the reference and defines a GI of 100.

Our recommended “safe starches” are significantly lower in GI than glucose.

White rice is typically listed with a GI of 70 or 72, but it varies by strain: Bangladeshi rice has a GI of 37, American brown rice of 50, Japonica (a white short-grained rice) of 48, Basmati rice of 58, Chinese vermicelli of 58, American long-grain rice of 61, risotto rice of 69, American white rice is 72, short-grain white rice is 83, and jasmine rice 89 (source).

Potatoes are a high-GI food but again the GI is highly variable. Baked white potatoes with the skin have a GI of 69, peeled their GI is 98. Yams have GI of 35 to 77 depending on how they are prepared, sweet potatoes of 44 to 94 (source).

With some foods the GI varies strongly with ripeness. Plaintains when unripe have a GI of 40 but when ripe the GI can reach 90 (source).

Taro has a GI of 48 to 56. That’s similar to many fruits, such as bananas which have a GI of 47 to 62. Tapioca has a GI of 70 if steamed, but can exceed 80 if boiled (source).

Gentle Cooking Lowers the Glycemic Index

As a rule, gentle cooking of starchy plants leads to a lower glycemic index and high cooking temperatures lead to a higher glycemic index.

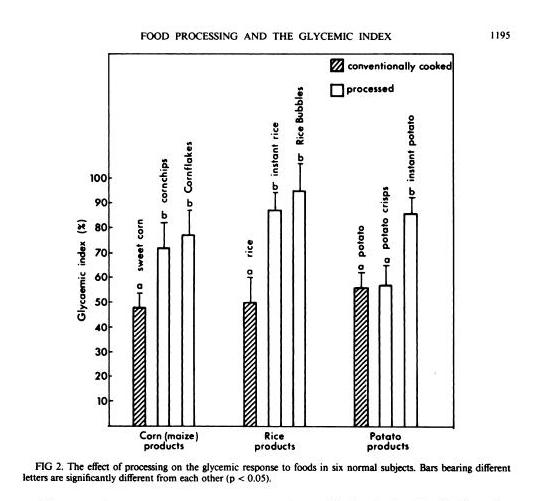

In general, industrially processed foods, which are often processed at very high temperatures to speed them through factories, have high GIs. A study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [1] compared home-cooked corn, rice, and potato with processed foods based on them (instant rice, Rice Bubbles, corn chips, Cornflakes, instant potato, and potato crisps), and the processed foods had consistently higher GIs:

Another study in the British Journal of Nutrition [2] looked at 14 starchy plants prepared in different ways and found that roasting and baking raised the GI:

GI value of some of the roasted and baked foods were significantly higher than foods boiled or fried (P<0.05). The results indicate that foods processed by roasting or baking may result in higher GI. Conversely, boiling of foods may contribute to a lower GI diet.

Perhaps cooking methods that dry out the plant increase the GI.

Meals Have Lower GI

GI is calculated by eating a single food and only that food.

But what happens when you eat a meal? You’re no longer eating one food, but a mixture of foods. The baked potato may come with meat and vegetables, and with butter on top.

You might think that a weighted average of the GI of the various foods might give a good indication of the GI of the meal. Then, since fat, meat, and vegetables have a low GI, you’d expect GI of the meal to be much lower.

It turns out that the GI of meals is low – in fact, it is even lower than the average GI of the foods composing the meal.

That is the result of a new study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [3]. Three meals were prepared combining a starch (potato, rice, or spaghetti) that digested to 50 g (200 calories) glucose with vegetables, sauce, and pan-fried chicken. The GIs of the meals were consistently lower than the values predicted using a weighted average of GIs of the meal components:

| Meal | Actual GI | Predicted GI |

| Potato | 53 | 63 |

| Rice | 38 | 51 |

| Spaghetti | 38 | 54 |

So eating a starch as part of a meal reduces GI to the range 38 to 53 – below the levels of many fruits and berries.

Fat Reduces GI

J Stanton has noted that adding a little fat to a starch is very effective in lowering its GI. In a post titled “Fat and Glycemic Index: The Myth of Complex Carbohydrates,” JS states that:

- Flour tortillas have a GI of 30, compared to a GI of 72 for wheat bread, because tortillas are made with lard.

- Butter reduces the glycemic index of French bread from 95 to 65.

- A Pizza Hut Super Supreme Pizza has a GI of 30, whereas a Vegetarian Supreme has a GI of 49.

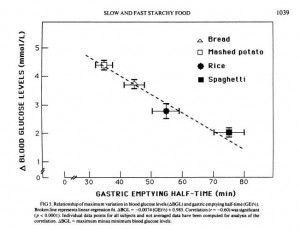

JS suggests that the reason fat does this is that it lowers the gastric emptying rate, and cites a study which showed that adding fat to starches could increase the gastric emptying time – the time for food to leave the stomach – by 50%. [4]

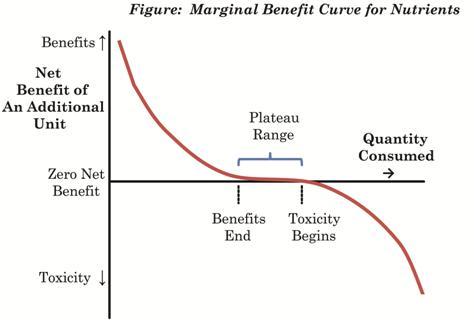

What’s interesting to me here is that what we really care about is not the glycemic index, but the peak blood glucose level attained after a meal. It is blood glucose levels above 140 mg/dl only that are harmful, and the harm is proportional to how high blood glucose levels rise above 140 mg/dl. So it’s the spikes we want to avoid.

But another paper shows that gastric emptying rate is even more closely tied to peak blood glucose level than it is to glycemic index. From [5]:

So combining a starch with fat may reduce peak blood glucose levels even more than it reduces the glycemic index; which is a good thing.

Dairy reduces GI

Dairy is effective at reducing GI:

[D]airy products significantly reduced the GI of white rice when consumed together, prior to or after a carbohydrate meal. [6]

It is not likely that dairy fat alone was responsible, because whole milk worked better than butter. However, low-fat milk only reduced the GI of rice by 16%, while whole milk reduced it by 41%. So clearly dairy fats are part of the recipe, but not the whole story; whey protein may also matter.

Fiber Reduces GI

Fiber is another meal element that reduces the rise in blood sugar after eating.

Removing fiber from starchy foods increases their glycemic index [7]; adding fiber decreases it. For instance, adding a polysaccharide fiber to cornstarch reduced its GI from 83 to 58; to rice reduced its GI from 82 to 45; to yogurt from 44 to 38. [8]

So it’s good to eat starches with vegetables – the foods richest in fiber.

Acids, Especially Vinegar, Reduce GI

Traditional cuisines usually make sauces by combining a fat with an acid. Frequently used sauce acids are vinegars and citric acid from lemons, limes, or other citrus fruits.

It turns that sauce acids can substantially reduce the GI of meals. The best attested is vinegar. From a study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition [6]:

In the current study, the addition of vinegar and vinegared foods to white rice reduced the GI of white rice. The acetic acid in vinegar was thought to be responsible for the antihyperglycemic effect. The amount of acetic acid to be effective could be as low as that found in sushi (estimated to be about 0.2–1.5 g/100 g). The antihyperglycemic effect of vinegar is consistent with other studies performed earlier (Brighenti et al, 1995; Liljeberg & Bjorck, 1998). Although vinegar could lower GI vales, the mechanism has rarely been reported. Most studies accounted the mechanism to be due to a delay in gastric emptying. In animal studies, Fushimi (Fushimi et al, 2001) showed that acetic acid could activate gluconeogenesis and induce glycogenesis in the liver after a fasting state. It could also inhibit glycolysis in muscles. [6]

Other acids also work. Pickled foods, which are sour due to lactic acid released by bacteria, reduce the glycemic index of rice by 27% if eaten before the rice and by 25% if eaten alongside the rice [6].

Wines, especially red wines, are somewhat acidic. I haven’t seen a study of how drinking wine with a meal affects glycemic index, but it is known observationally that wine drinkers have better glycemic control and, often, long lives. [9]

So What’s the Healthiest Way to Eat “Safe Starches”?

One way to limit the likelihood of reaching dangerous blood sugar levels after a meal is by eating a relatively “low carb” diet. We recommend that sedentary people eat about 400 to 600 carb calories per day. This limits the amount eaten at any one sitting to about 200 calories / 50 g, which is the amount of a typical glucose tolerance test. It is an amount the body is well able to handle.

But the manner in which carbs are eaten may be just as important as the amount.

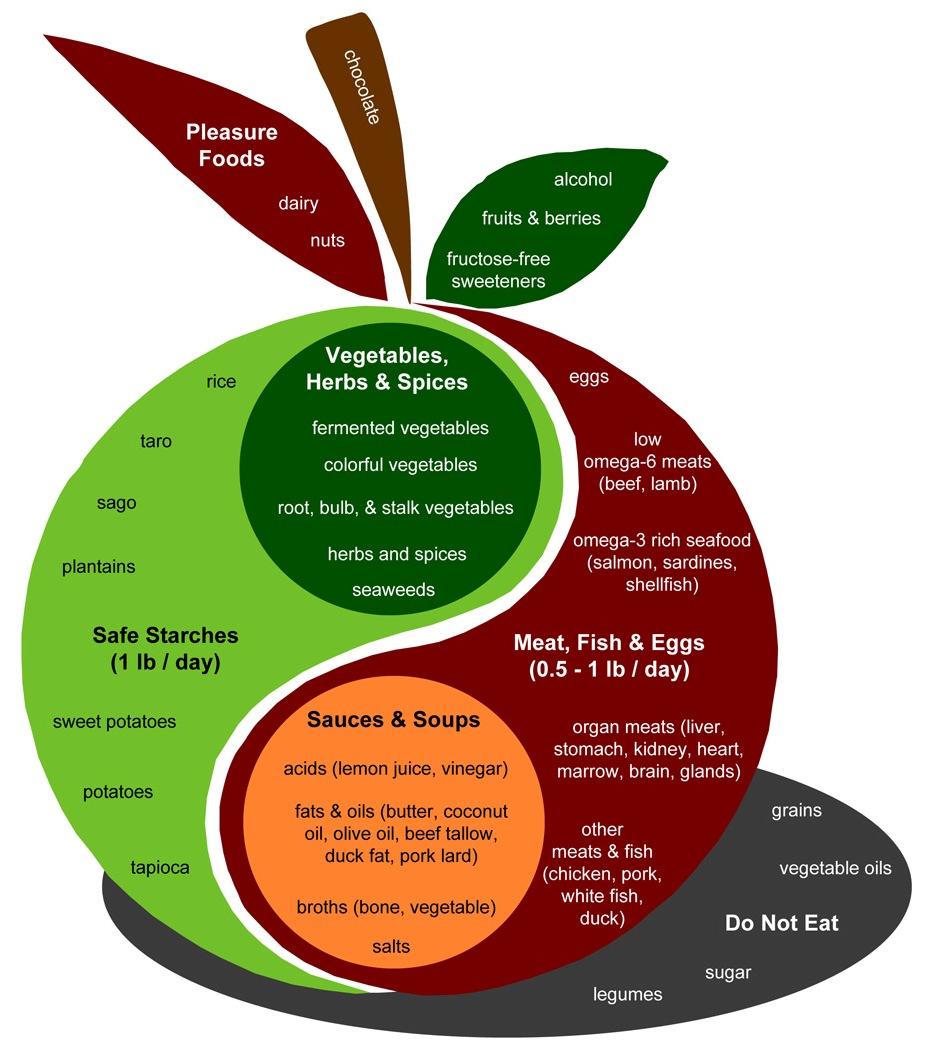

Let’s look again at the Perfect Health Diet Food Plate:

The design of a PHD meal is found in the body of the apple. Assuming two meals a day, the recipe is to combine:

- A safe starch (roughly ½ pound, which translates to 150 to 300 carb calories);

- A meat, fish, or egg (¼ to ½ pound);

- A sauce made up of fats and acids such as lemon juice or vinegar;

- Vegetables, preferably including fermented vegetables with their healthy acids;

- (Optionally) some dairy or a glass of wine.

This is precisely the recipe which science has found minimizes the elevation of blood glucose after meals.

It seems reasonable to expect that a meal designed in this fashion will have a glycemic index around 30. The odds of 200 carb calories with a glycemic index of 30 generating blood sugar levels that are dangerous – 140 mg/dl or higher – in healthy people is very low. Even in diabetics, it may be uncommon.

So, yes, Virginia. There is a Santa Claus, and you can eat safe starches and avoid hyperglycemia too!

References

[1] Brand JC et al. Food processing and the glycemic index. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985 Dec;42(6):1192-6. http://pmid.us/4072954.

[2] Bahado-Singh PS et al. Food processing methods influence the glycaemic indices of some commonly eaten West Indian carbohydrate-rich foods. Br J Nutr. 2006 Sep;96(3):476-81. http://pmid.us/16925852.

[3] Dodd H et al. Calculating meal glycemic index by using measured and published food values compared with directly measured meal glycemic index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Oct;94(4):992-6. http://pmid.us/21831990.

[4] Thouvenot P et al. Fat and starch gastric emptying rate in humans: a reproducibility study of a double-isotopic technique. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59(suppl):781S.

[5] Mourot J et al. Relationship between the rate of gastric emptying and glucose and insulin responses to starchy foods in young healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Oct;48(4):1035-40. http://pmid.us/3048076.

[6] Sugiyama M et al. Glycemic index of single and mixed meal foods among common Japanese foods with white rice as a reference food. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jun;57(6):743-52. http://pmid.us/12792658. Full text: http://www.nature.com/ejcn/journal/v57/n6/full/1601606a.html.

[7] Benini L et al. Gastric emptying of a solid meal is accelerated by the removal of dietary fibre naturally present in food. Gut. 1995 Jun;36(6):825-30. http://pmid.us/7615267.

[8] Jenkins AL et al. Effect of adding the novel fiber, PGX®, to commonly consumed foods on glycemic response, glycemic index and GRIP: a simple and effective strategy for reducing post prandial blood glucose levels–a randomized, controlled trial. Nutr J. 2010 Nov 22;9:58. http://pmid.us/21092221.

[9] Perissinotto E et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in older lifelong wine drinkers: the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010 Nov;20(9):647-55. http://pmid.us/19695851.

Recent Comments