Every week I collect many more interesting links than I can blog about, so I thought I’d include in Saturday posts links to interesting material on the Web.

Here are some things I found noteworthy this week:

(1) Chris Kresser has concluded that 2 food pyramids are better than one. His fat and carb pyramids could serve as a visual summary of our diet:

(2) US children who regularly buy school lunches are 29% more likely to become obese than those who bring lunch from home.

School lunch programs have to follow official US dietary guidelines, which favor the subsidized crops of wheat, corn, and soybeans. The USDA recently banned the potato from school lunches in an effort to get kids to eat more grains.

Since food toxins cause obesity, this outcome is just what we would have predicted.

(3) Giving nitrate to athletes causes their mitochondria to become more efficient.

Spinach is rich in nitrates. Popeye was right! Spinach does make you stronger.

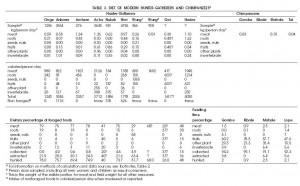

(4) More China Study data: Ned Kock shows that fat is the safest macronutrient, animal food is safer than plant food, but that rice and vegetables are OK.

(5) Perfect Health Diet, the book, is “Paleo for engineers”. Accurate?

(6) Engineers, our video of the week is for you. When I first saw this thing, I thought it was a device for giving nightmares to young children.

Good thing Dr. Deans didn’t choose this for her kids’ nightlight! The blue lights are bad for melatonin.

Recent Comments