If there will be a general theme to our second year of blogging, it will be chronic infections – how they interact with the body to promote disease, and how we can use diet-related techniques to successfully combat them.

Blood lipids, such as LDL and HDL cholesterol, provide a fascinating window into health. We’ve already discussed both LDL and HDL (Low Carb Paleo, and LDL is Soaring – Help!, March 2, 2011; Answer Day: What Causes High LDL on Low-Carb Paleo?, March 3, 2011; HDL and Immunity, April 12, 2011; HDL: Higher is Good, But is Highest Best?, April 14, 2011; How to Raise HDL, April 20, 2011), but there’s quite a bit more to be said.

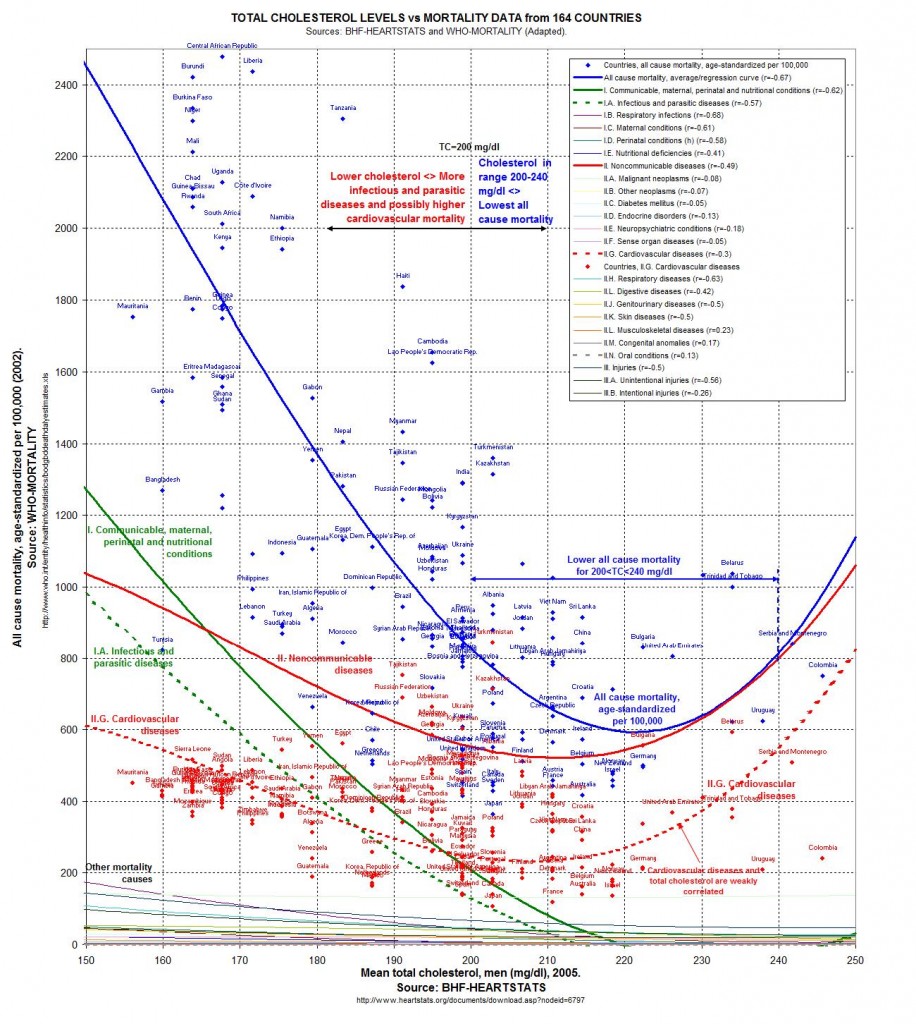

The extraordinary Portuguese blogger Ricardo Carvalho, better known as O Primitivo, of Canibais e Reis did some great work a few years back assembling World Health Organization statistics into an Excel database. One of the fruits of this labor was that he was able to correlate disease rates against serum cholesterol levels for all the countries in the database. His post about that is here and he created a great graphical representation of the results which I’ve reproduced here (click to enlarge):

There’s a lot of interesting information in this graph.

On the upper right are some correlation coefficients between serum cholesterol and disease incidence. Most diseases are either uncorrelated with cholesterol, or negatively correlated, meaning that mortality goes up as cholesterol goes down.

Minimum mortality is found in countries with average cholesterol between 200 and 240 mg/dl. Mortality rises sharply as cholesterol levels fall below 200 mg/dl.

No ecological fallacy

When aggregating over populations, it’s possible to get misleading results – an outcome called the “ecological fallacy”. However, I think this relationship is pretty solid.

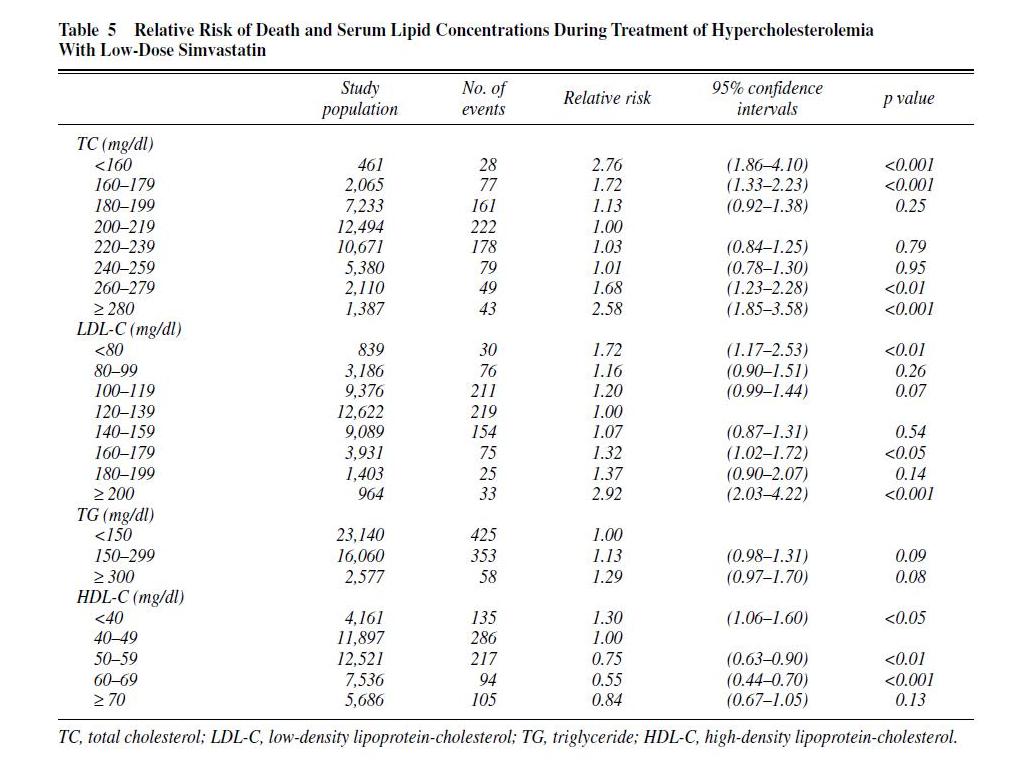

It’s been confirmed in individuals in clinical trials. For instance, in the Japan Lipid Intervention Trial, here was the table of mortality as a function of serum lipids:

You’ll note that the “relative risk” of dying was lowest for TC between 180 and 260, LDL-C between 80 and 160, and HDL-C between 60 and 70.

The minimum mortality region of O Primitivo’s national samples falls right in the middle of the JLIT minimum mortality region.

Infectious disease mortality depends strongly on cholesterol levels

By far the strongest dependence of mortality on cholesterol levels is found for infectious diseases. Infectious disease mortality is shown by the dashed green curve.

Infectious disease mortality approaches zero where TC averages between 215 and 245 mg/dl. It rises very sharply as TC falls. Over a wide range of TC, for every 10 mg/dl drop in average TC, mortality rises by 200 infectious deaths per year per 100,000 population.

Other diseases are partly infectious in origin

As regular readers know, I believe that many other “noncommunicable” diseases are actually caused in part by chronic infections. Cardiovascular disease is one – atherosclerotic lesions are universally found to be infected, macrophages usually need to be infected in order to become “foam cells” which contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation, and the infectious burden in lesions drives the risk of fragmentation of plaque into the clots which cause heart attacks and strokes.

If cardiovascular disease is partly due to infections, and the protective effect of cholesterol against infections is present here, then we should expect cardiovascular disease mortality (shown in the red dashed line) to rise as TC falls.

It does. Mortality from cardiovascular disease starts rising as TC falls below 205 mg/dl and rises by about 200 infectious deaths per year per 100,000 population for every 25 mg/dl drop in average TC.

Causality probably runs in both directions

We can’t directly infer causality from these statistics. Consider two possible directions of causality:

- Serum cholesterol – LDL and HDL – help defend against infections. As long as you have these infection-fighting lipids in your blood, infections can’t kill you.

- Infections destroy LDL and HDL, and the more severe the infection, the lower blood cholesterol goes. By the time the infection is severe enough to kill you, TC is very low. So countries with high infectious burden have both low TC and high infectious mortality.

The first line of causality is certainly true. I’ve already discussed the important infection-fighting properties of HDL – in fact I’ve argued that infection fighting, not cholesterol transport, is the primary function of HDL (See HDL and Immunity, April 12, 2011). As I’ll discuss, LDL also has immune functions.

The second line of causality is also quite likely. Pathogens evolve ways to suppress immunity; that is what makes them effective pathogens. If LDL and HDL are crucial for immune defense, then pathogens will have found ways to destroy or damage them.

In this series I would like to explore these interactions between blood lipids and infections a little more deeply. They may lead us to ways we can tweak our diet to improve our defenses against disease — or help doctors recognize under what circumstances taking statins will raise, not lower, cardiovascular disease risk.

References

[1] Matsuzaki M et al. Large scale cohort study of the relationship between serum cholesterol concentration and coronary events with low-dose simvastatin therapy in Japanese patients with hypercholesterolemia. Circ J. 2002 Dec;66(12):1087-95. http://pmid.us/12499611.

Recent Comments