We’re in the midst of a series exploring therapeutic ketogenic diets. Our immediate goal is to help the NBIA kids, Zach and Matthias, but most of the ideas will be transferable to other conditions – and even to healthy people who engage in occasional or intermittent ketogenic dieting for disease prevention.

Clinical ketogenic diets often produce stunted growth and bone and muscle loss. Today I want to look at this phenomenon and what we can do to avoid it.

Bone Failure and Stunted Growth

First, some data. A review of childhood epilepsy patients on ketogenic diets prescribed by Johns Hopkins Hospital doctors points out problems experienced by the children:

- Weak bones. Skeletal fractures occurred in 6 of 28 children following the ketogenic diet for 6 years; 4 children had fractures at separate locations and times. [1]

- Stunted growth. By the end of the 6 years, 23 of the 28 children were in the bottom tenth by height of their age group. [1]

Other negative effects highlighted in the review include kidney stones (7 children developed stones) and dyslipidemia (total cholesterol as high as 383 mg/dl). [1] As we’ve discussed in previous posts, these are probably caused by malnutrition. Kidney stones are usually due to deficiency of antioxidants; dyslipidemia due to deficiency of minerals, vitamins, or choline.

It’s a little hard to nail down the exact cause of the bone fractures and stunted growth because the diets were so atrocious.

First, children were told to eat calorically restricted diets to invoke the starvation response:

Calories were restricted to 75% of estimated daily needs, and fluids were calculated at 80% of daily requirements. [1]

Second, some of the children were fed formula – not real food:

[C]hildren fed only with formula all received a combination of Ross Carbohydrate-Free, Mead Johnson Microlipid, and Ross Polycose formulas to provide a nutritionally complete diet … [1]

For those keeping score, Ross Carbohydrate Free consists of soy protein isolate, high oleic safflower oil, soy oil, and coconut oil, plus vitamins and minerals. Microlipid is a safflower oil emulsion. Ross Polycose is hydrolyzed cornstarch.

(As Jake mentioned in the comments, another commonly prescribed formula is Ketocal, which consists of hydrogenated soybean oil, dry whole milk, refined soybean oil, soy lecithin, and corn syrup solids. Jake’s pithy analysis: “You might as well hold a gun to the head of the child and pull the trigger.”)

There are two problems with this diet design. First, purified diets are notoriously unhealthy; they are missing all kinds of helpful compounds found in real food. Animals do poorly on such diets, as Chris Masterjohn recently noted. Chris quotes the American Institute of Nutrition:

Purified diets without added ultratrace elements support growth and reproduction, but investigators have noted that animals exposed to stress, toxins, carcinogens or diet imbalances display more negative effects when fed purified diets than when fed cereal-based diets.

The second problem, from my point of view, is that they made little use of short-chain fats and ketogenic amino acids to make the diet ketogenic. Instead, they relied on protein and carb restriction and overall calorie restriction to force ketone production. In short, they intentionally starved the kids.

Obviously, starvation tends to produce stunted growth; this is why North Koreans are shorter than South Koreans.

I believe such starvation is totally unnecessary. Use of short-chain fats and ketogenic amino acids can trigger high ketone production even on a nourishing diet.

Nevertheless, even an awful diet is better than the best pharmaceutical drugs:

All of the parents interviewed preferred the diet over medications; 12 cited fewer side effects (such as cognitive dulling, sedation, ataxia, and behavioral problems) from medications that were successfully discontinued, and 11 cited decreased seizure frequency over medications as their primary reason. [1]

Muscle Loss

Another, closely related, problem on ketogenic diets is loss of muscle. You don’t often see bodybuilders or Olympic weight lifters who eat a continuously ketogenic diet. It can be hard to add muscle, especially on protein and carb restricted diets.

This is true even if the diet is not calorically restricted. Which brings us to a rat study [2] discussed by CarbSane in her post “Ketogenic Diet increases Fat Mass and Fat:Total Body Mass Ratio”.

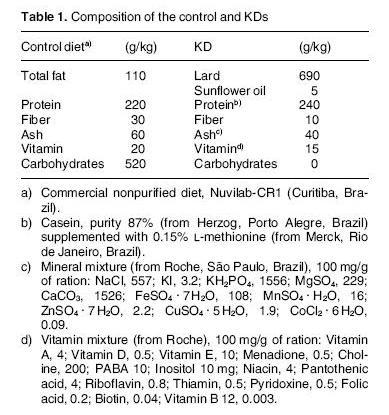

The study compared two diets, a control diet and a ketogenic diet:

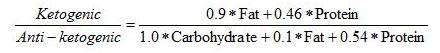

The ketogenic diet had more than 6 times the fat of the control diet, the same amount of protein, and no carbohydrate at all. Since protein has to be converted to glucose on zero-carb diets, this ketogenic diet is actually protein restricted. The paper confirms that the ketogenic diet operated on the margin of severe protein deficiency:

[P]reliminary experiments using a KD with 20% protein (as used in children) caused undernutrition of the rats as shown by a significant loss of weight and hair (data not shown). For this reason we used 24% protein, equivalent to that used in controls. [2]

The ketogenic diet also had lower micronutrient levels (“Ash” and “Vitamin”) than the control diet, and much higher omega-6 levels.

Rats were fed ad libitum, meaning they could eat as much as they liked; they chose to eat twice as many calories on the ketogenic diet. This suggests that the diet was protein+carbohydrate deficient.

When protein+carbohydrate intake is deficient, muscle will tend to be catabolized for protein. This causes muscle loss. Meanwhile, the starvation response – especially when more calories are eaten – tends to lead to fat mass gain.

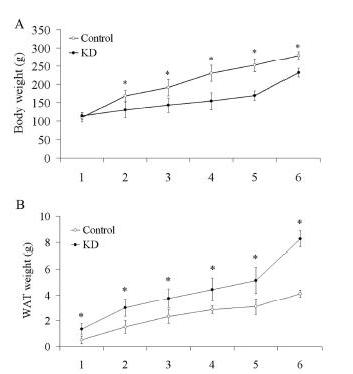

Muscle loss and fat mass gain are exactly what happened to these rats. This is from Figure 1:

You can see in panel A that rats on the control diet weighed more than rats on the ketogenic diet. But panel B shows that rats on the ketogenic diet had more white adipose tissue (WAT). The ketogenic diet rats had more fat mass but less body mass; they had obviously lost muscle and bone mass.

I believe this is due to eating too little protein and carbohydrate. Protein+carbs were 13% on the ketogenic diet, 75% on the control diet. 13% is just too little. For humans, we recommend a minimum protein+carb intake of 600 calories per day, which is about 30% of calories for a sedentary adult. Rats kept in shoebox cages are, of course, sedentary whether they would like to be or not.

I draw two conclusions:

1. If you’re deficient in protein+carb, you’ll lose muscle; and

2. Losing muscle may invoke the starvation response, causing you to gain fat.

The paper did not measure length of the rats, but I would bet that the ketogenic diet rats were not only lighter, but shorter as well.

Like the children on Johns Hopkins Hospital’s diet for epilepsy, these malnourished rats experienced stunted growth.

What is the alternative?

As we discussed in the first post in this series, Ketogenic Diets, I: Ways to Make a Diet Ketogenic, there are 3 ways to make a diet ketogenic. One of them is severe protein+carb restriction, but the other two – short-chain fat consumption and supplementation of the ketogenic amino acids lysine and leucine – can generate ketosis even if substantial carbs and protein are eaten.

So it’s worth exploring: with consumption of these ketogenic nutrients, plus substantial carbs and protein, can the health impairments of clinical ketogenic diets be avoided?

Via Nigel Kinbrum comes an interesting paper [3] exploring the use of branched-chain amino acids as an adjunct to ketogenic diets for epileptic children. Most branched-chain amino acids are ketogenic, so this is a good test of my hypothesis.

The study supplemented 45.5 g leucine, 30 g isoleucine, and 24.5 g valine to 17 epileptic children on the ketogenic diet. Leucine is ketogenic, valine glucogenic, isoleucine can be either. The results:

None of our patients had a remarkable reduction in the level of urine ketosis after the supplementation of branched chain amino acids. Moreover, no exacerbation of seizures in terms of frequency or intensity was noted in any of the 17 patients of the study.

Regarding the improvement of seizures, we found 3 patients who had already achieved a reduction of seizures on the ketogenic diet to experience a complete cessation of seizures, while 2 other patients had a further reduction of seizures from 70% on ketogenic diet to 90%. In 2 other patients, the percentage of improvement with the branched chain amino acids supplementation was even greater, achieving 50% and 60% before branched chain amino acids supplementation to 80% and 90% afterward. One patient had 50% improvement (Table 1)….

According to the parents’ and teachers’ reports, improvement was noted regarding behavior and cognitive functions in 9 of 17 patients, particularly in the fields of concentration, learning ability, and communication skills with other children. It is remarkable that 1 of our children had improved so much that she is now applying to attend normal grade level for her age. [3]

There were no significant side effects; only a transient elevation of heart rate at the start of supplementation.

Importantly, supplementing these amino acids allowed more protein to be consumed for the same degree of ketosis:

The first observation we made was that by adding the branched chain amino acids, the fat-to-protein ratio of the diet changed from 4:1 to around 2.5:1 (depending on the patient’s weight) without causing any alteration in ketosis. [3]

Toxicity of Ketogenic Amino Acids

It may be possible to go higher than 45 g leucine per day. The authors acknowledge that they were being cautious in limiting branched-chain amino acid supplementation to that dose:

There is also the question of why we did not try to further increase the amount of branched chain amino acids supplementation because there were no side effects or a change in ketosis. As far as we know, it is the first time branched chain amino acids have been used in patients with epilepsy and we had to be very cautious with their administration. [3]

There is a risk of toxicity at high doses of leucine supplementation unless it is accompanied by the other branched-chain amino acids, isoleucine and valine:

Could we provide leucine alone as the most ketotic of branched chain amino acids? Providing exclusively leucine as an adjunctive treatment to ketogenic diet is impossible because it is toxic when consumed out of proportion to valine and isoleucine…. Lack of valine and isoleucine inhibits protein synthesis. The consequence is that leucine should not be consumed in large amounts without valine and isoleucine, even though only leucine promotes protein synthesis. [3]

Possibly this assessment is over-pessimistic: in rats leucine and isoleucine without valine had no significant toxicity at 5% of energy. [4] Leucine alone lacked toxicity in rat studies:

Recent studies in rats demonstrate no obvious toxicity, even with the administration of BCAA in doses that greatly exceed probable human intake. [5]

L-leucine, administered orally during organogenesis at doses up to 1000 mg/kg body weight, did not affect the outcome of pregnancy and did not cause fetotoxicity in rats. [6]

Lysine, the other purely ketogenic amino acid, is generally considered to have no significant toxicity. [7]

Considerations for the NBIA Kids

For the NBIA kids, Zach and Matthias, we want the diet to be as ketogenic as possible. This is important because glucose is unable to feed neurons due to the inability to make CoA in mitochondria and bring pyruvate into the citric acid cycle. If only ketones can feed the brain, it’s important to make as many of them as possible.

So we would like to give a lot of lysine and leucine. If we have to add other branched-chain amino acids to avoid leucine toxicity, it would be better to add isoleucine, which can be ketogenic, than valine which is only glucogenic.

The BCAA-for-epileptic-children paper [3] can help us judge safe dosages. Supplemental leucine can be at least 45 g/day, since that was give successfully to the epileptic kids. Lysine can be at least as much, since it is non-toxic. Already we’re up to around 400 calories from supplemental lysine and leucine, which is a healthy amount.

Is it necessary to give a lot of isoleucine and valine with leucine? That’s unclear. Leucine by itself may have special benefits for NBIA/PKAN kids.

Paper [5] shows an interesting set of reactions in the brain: leucine plus pyruvate can be transformed into alpha-ketoisocaproate plus alanine in brain mitochondria. This is extremely important, perhaps, because removing pyruvate from brain mitochondria might prevent iron accumulation in the brain.

Iron accumulation in PKAN is thought to result from pyruvate buildup in mitochondria. Pyruvate attracts cysteine, because pyruvate and cysteine are normally converted to downstream products with the aid of the PanK2 enzyme that is lost in PKAN. With the loss of PanK2, pyruvate and cysteine build up, and the cysteine chelates iron, trapping it in brain mitochondria.

If leucine can remove pyruvate from brain mitochondria, it may also diminish cysteine levels and therefore reduce iron trapping in mitochondria. The iron buildup that is so debilitating might be prevented or mitigated.

Conclusion

I believe the extreme limits on carb and protein intake in conventional clinical ketogenic diets are responsible for their growth stunting, muscle destroying, fattening effects.

In order to supply sufficient protein and carbs while maintaining ketosis, it is necessary to provide ketogenic short-chain fats and amino acids.

Clinical testing of such supplemented diets has so far produced encouraging results. Providing supplemental amino acids to epileptic children on ketogenic diets improved their health and allowed them to maintain ketosis with higher protein intake. Seizure frequency was reduced even as side effects diminished.

Personally, I wouldn’t attempt a long-term ketogenic diet without the aid of coconut oil (or MCTs), lysine, and the branched chain amino acids.

For the NBIA/PKAN kids, it seems that the amino acid supplements should be some mix of lysine, leucine, isoleucine, and valine, with the isoleucine and valine included solely to reduce leucine toxicity. The optimal amount of isoleucine and valine should be smaller than is found in branched-chain amino acid supplements, since leucine by itself may help prevent iron accumulation and increase ketosis. Also, one rat study [4] indicates that isoleucine alone, excluding valine, might be enough to relieve leucine toxicity. Excluding valine would increase the ketogenicity of the supplement mix.

I think the NBIA/PKAN kids will need to experiment with primarily lysine and leucine, and secondarily isoleucine and BCAA supplements, to see what mix works best for them.

References

[1] Groesbeck DK et al. Long-term use of the ketogenic diet in the treatment of epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006 Dec;48(12):978-81. http://pmid.us/17109786. Hat tip CarbSane.

[2] Ribeiro LC et al. Ketogenic diet-fed rats have increased fat mass and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase activity. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008 Nov;52(11):1365-71. http://pmid.us/18655006. Hat tip CarbSane.

[3] Evangeliou A et al. Branched chain amino acids as adjunctive therapy to ketogenic diet in epilepsy: pilot study and hypothesis. J Child Neurol. 2009 Oct;24(10):1268-72. http://pmid.us/19687389. Hat tip Nigel Kinbrum.

[4] Tsubuku S et al. Thirteen-week oral toxicity study of branched-chain amino acids in rats. Int J Toxicol. 2004 Mar-Apr;23(2):119-26. http://pmid.us/15204732.

[5] Yudkoff M et al. Brain amino acid requirements and toxicity: the example of leucine. J Nutr. 2005 Jun;135(6 Suppl):1531S-8S. http://pmid.us/15930465.

[6] Mawatari K et al. Prolonged oral treatment with an essential amino acid L-leucine does not affect female reproductive function and embryo-fetal development in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Sep;42(9):1505-11. http://pmid.us/15234081.

[7] Tsubuku S et al. Thirteen-week oral toxicity study of L-lysine hydrochloride in rats. Int J Toxicol. 2004 Mar-Apr;23(2):113-8. http://pmid.us/15204731.

Recent Comments