The Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes trial has been halted two years early. Here’s Gina Kolata in The New York Times:

The study randomly assigned 5,145 overweight or obese people with Type 2 diabetes to either a rigorous diet and exercise regimen or to sessions in which they got general health information. The diet involved 1,200 to 1,500 calories a day for those weighing less than 250 pounds and 1,500 to 1,800 calories a day for those weighing more. The exercise program was at least 175 minutes a week of moderate exercise.

But 11 years after the study began, researchers concluded it was futile to continue — the two groups had nearly identical rates of heart attacks, strokes and cardiovascular deaths.

It’s clearly a negative result for “eat less, move more” as a health strategy for obese diabetics.

Was “Eat Less Move More” Harmful?

A few Paleo bloggers are not surprised; indeed, Peter Dobromylskyj speculates that all-cause mortality – which Ms. Kolata and the NIH press release do not report – may have been higher in the “eat less, move more” intervention group:

It seems very likely to me that more people died in the intervention group than in the usual care group, but p was > 0.05.

Call me a cynic, but I think they stopped the trial because they could see where that p number was heading.

Peter may be a cynic but cynics are sometimes right, and I will bet that he’s right about this. In general, calorie restriction and exercise are better attested against cardiovascular disease than against other health conditions, so if death rates from CVD were identical in the two arms after 11 years, it’s quite likely death rates from other causes were higher in the intervention arm.

Our Theory

We discuss in our new Scribner edition two reasons why “eat less, move more” can backfire:

- On a malnourishing diet, “eat less” means even greater malnourishment. Less of a bad diet is a worse diet.

- Excessive exercise may over-stress the body and harm health. In diseased people, the volume at which exercise becomes excessive may not be that high.

On the other hand, ultimately some form of “eat less, move more” is needed if optimal health is to be attained:

- An energy deficit – eating less than the body expends – is necessary to lose fat mass, and obesity is probably incompatible with optimal health.

- About 20 to 30 minutes of exercise per day at the intensity of running or jogging is needed for optimal health, probably due to the role of daytime activity in entraining circadian rhythms (see “Physical Activity: Whence Its Healthfulness?”, October 11, 2012). Most people would need to “move more” to achieve this.

So the challenge in weight loss is two-fold: It’s necessary to adopt a healthy diet in which malnourishment doesn’t occur despite calorie restriction, and to find a healthy level of exercise that improves health without overstressing the body.

Look AHEAD: Bad Dietary Advice

The Look AHEAD Study Protocol tells us what the intervention group was told to do.

From page 29, here is the diet advice:

The recommended diet is based on guidelines of the ADA and National Cholesterol Education program [96,97] and includes a maximum of 30% of total calories from total fat, a maximum of 10% of total calories from saturated fat, and a minimum of 15% of total calories from protein.

This gives 55% carbs and probably 10% omega-6 fat. The omega-6 intake is far too high – for weight loss and good health, omega-6 intake should be less than 4% – and so is the carb intake – for diabetics, reducing carbs to 30% or less is highly desirable.

From page 30, here is the exercise advice:

The physical activity program of Look AHEAD relies heavily on unsupervised exercise, with gradual progression toward a goal of 175 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week by the end of the first six months. Exercise bouts of ten minutes and longer are counted toward this goal. Exercise is recommended to occur five days per week.

Moderate-intensity walking is encouraged as the primary type of physical activity.

I think this is reasonable advice. It translates to 35 minutes per day for 5 days. The intensity is quite low. This level of exercise is hardly likely to be excessive; indeed, it’s probably grossly insufficient for optimal health. It represents about a mile and a half of walking per day, five days per week. This may have been a homeopathic level of activity.

There is another reason the exercise may have produced no observable benefit. Since I believe the health benefits of exercise occur primarily through circadian rhythm entrainment, it’s likely that daytime exercise is much more beneficial than night-time exercise. Night-time exercise might be ineffective or even harmful to health if it disrupts circadian rhythms.

Unfortunately many people find it difficult to find time during the day for exercise. If the walking was performed at night, even the modest benefits of the activity may have been lost.

Weight and Health: What’s the Direction of Causation?

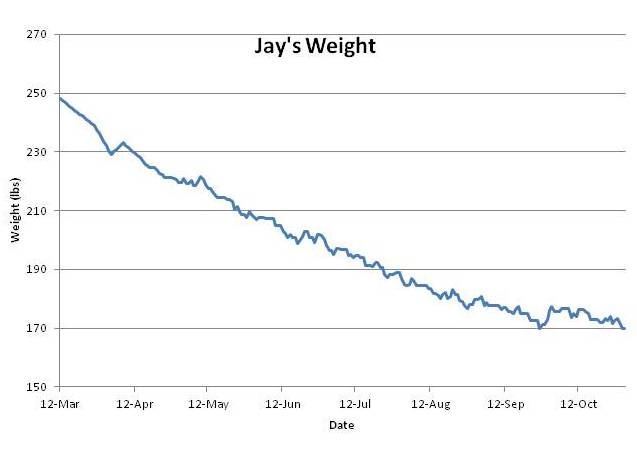

The one “success” of Look AHEAD was that it brought about some weight loss: the intervention group lost 5% of their original weight.

We know that obesity is associated with poor health. Since causation implies correlation, the existence of this correlation suggests that either (1) obesity causes poor health, (2) poor health causes obesity, or (3) some third factors cause both obesity and poor health.

The Look AHEAD study presumed (1) – that obesity causes poor health. The “eat less, move more” intervention was wholly directed at weight loss. If obesity is the cause of poor health, Look AHEAD should have improved health. It didn’t. This tells us that the direction of causality is either (2) or (3). Obesity doesn’t impair health; other factors that impair health cause obesity.

It’s easy to make faulty inferences about the direction of causation. The Look AHEAD scientists made the same mistake this woman did:

Conclusion

The basic flaw in the Look AHEAD study was that it was designed to bring about weight loss, and hoped that weight loss would improve health.

A better intervention would seek to improve health through a more PHD-like diet and through circadian rhythm therapies. Successful health improvement would, more than likely, lead to weight loss.

For the overweight and for diabetics, the focus should not be on weight, but on health. Improve health, and weight loss will follow. Focus on weight with a simple-minded “eat less, move more” intervention without tending to the quality of your diet and lifestyle, and you might be doing yourself more harm than good.

Recent Comments