We’re positive toward some dietary antioxidants:

- Vitamin C is one of our supplement recommendations.

- We also recommend higher-than-typical dietary intakes of zinc and copper, key ingredients of the antioxidant zinc-copper superoxide dismutase.

- We recommend high intakes of extracellular matrix material in soups and stews. This is rich in glycine, a component of glutathione, a key antioxidant. N-acetylcysteine, which provides the other amino acid component of glutathione, is one of our therapeutic supplements.

- Although we don’t normally recommend supplementing vitamin E, it is listed among our optional supplements, and we believe significant numbers of people might benefit from supplementing mixed tocotrienols.

- Although we don’t recommend supplementing it, our book notes the importance of dietary intake of selenium, which is critical for an enzyme that recycles glutathione.

A fashionable contrary view has arisen: antioxidants not only don’t help, they can do harm by interfering with oxidative signaling pathways.

Adel Moussa, proprietor of Suppversity, has promulgated this view, especially the idea that antioxidants interfere with the response to exercise. In a post last week, “Bad News For Vitamin Fans – C + E Supplementation Blunts Increases in Total Lean Body and Leg Mass in Elderly Men After 12 Weeks of Std. Intense Strength Training,” he looked at a new study by Bjørnsen et al [1]. In the comments here, Spor asked me to address Adel’s post, and other readers expressed interest too.

The Bjørnsen Study: Muscle Size

In this new study, Bjørnsen and collaborators put a group of elderly men on a strength training regimen. Half the men were put on supplements – 1000 mg per day of vitamin C and 235 mg (350 IU) per day of the alpha-tocopherol form of vitamin E – and half on placebo. They then assessed the response to 12 weeks of exercise.

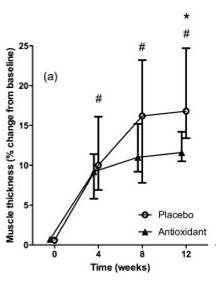

Both groups gained muscle mass, but the placebo group gained more. Total lean mass, and the thickness of the rectus femoris muscle (one of the quadriceps), increased more in the placebo than the antioxidant group. The lean mass increase averaged 3.9% in the placebo group, 1.4% in the antioxidant group. Here’s the plot of muscle thickness in the rectus femoris:

This muscle increased in thickness an average of 16.2% in the placebo group, 10.9% in the antioxidant group.

So far, so solid: it looks like muscle size will be larger if you don’t take antioxidants.

Adel concludes:

[Y]ou shouldn’t fall for … the bogus false promise that suffocating all the flames by using exorbitant amounts of antioxidants (and I am as this study shows talking about 10x the RDA not just 100x the RDA) would be good for you, let alone your training progress and muscle gains…. [Y]ou cannot recommend extra-vitamins for people who work out – specifically not the elderly.

I disagree.

The Trouble with Biomarkers

We have to use biomarkers to assess health, because the things we really care about – like how long we will live – cannot be determined on the time scales we need to make decisions in.

But no biomarker is a perfect assessment of health. There are always regimes in which a biomarker can look “better” but health can worsen.

Muscle size is no different. Other things being equal, more muscle is better than less muscle. But there are ways to increase muscle size that harm health. We have to look at the increase in muscle size in the placebo group and ask: was this good or bad?

The Bjørnsen Study: Strength

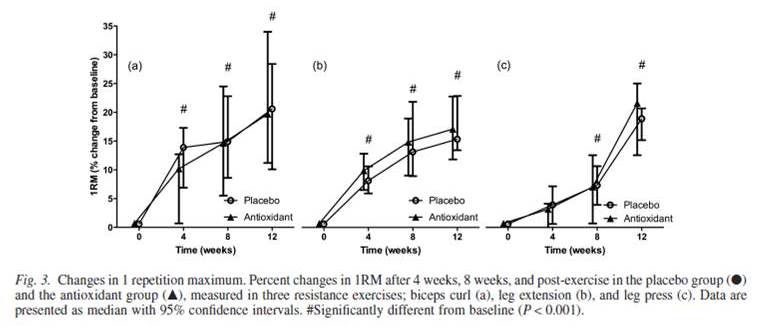

Fortunately, Bjørnsen and colleagues also reported another key biomarker: strength, as indicated by 1 rep maximum weight. Here is the data:

The exercises that utilize the rectus femoris muscle, the one that grew biggest in the placebo group, are the leg extension (b) and leg press (c). And here we see something interesting: in both cases, the antioxidant group increased their 1RM by more than the placebo group. Yes, the improvement was not statistically significant. But it was there. According to the text, on average, the antioxidant group increased their leg press 1RM by 18.7%, the placebo group by 15.8%.

So the antioxidant group gained more strength but less size than the placebo group. Which group was made healthier by the program?

I’ll put my money down on this: the smaller muscle that can exert more force is the healthier muscle. A gargantuan but weak muscle is an unhealthy muscle.

Large Muscle Size Can Be a Sign of Poor Health

To see that large muscles may be unhealthy, consider the health condition of cardiomegaly – an enlarged heart. When the heart tissue is dysfunctional and incapable of exerting as much strength as it should, the heart grows larger to compensate. People who have such an oversized but weak heart often die an early death.

We should consider whether something similar was going on in the placebo group of the Bjørnsen study. Their leg muscles grew larger to compensate for weakness. They needed more mass to accomplish less than the antioxidant group.

What causes cardiomegaly? One contributing factor is a deficiency of antioxidants. When antioxidants are deficient, oxidative stress generated during exertion leads to lipid peroxidation and tissue necrosis.

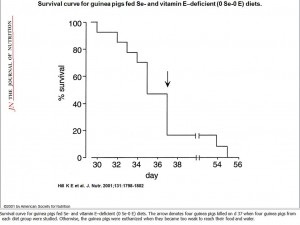

One of my favorite nutritional studies – I always show it at the Perfect Health Retreat to demonstrate the existence of multi-nutrient deficiency diseases, diseases that appear only when you are deficient in multiple nutrients at the same time – is a study by Kristina Hill and collaborators at Vanderbilt in 2001. [2] The running title is “Myopathy resulting from combined Se and E deficiency” and that summarizes it well. Guinea pigs were put on one of four diets – a control diet, the control diet but deficient in vitamin E, the control diet but deficient in selenium, or the control diet with both vitamin E and selenium removed.

Something interesting happened to the guinea pig muscles:

These are quadriceps muscles – the same muscle whose size was altered in the Bjørnsen study. Panel (D) shows a healthy muscle from the control group. The muscle fibers are long, straight, and parallel to one another. Panels (B) and (C), the low vitamin E and low selenium groups respectively, are mildly damaged but still functional. However, in panel (A), the group deprived of both selenium and vitamin E, the muscle fibers are severely damaged. This muscle cannot exert force.

In the group deprived of both selenium and vitamin E, the loss of strength continued until the guinea pigs could no longer stand or move. At that point they lost the ability to feed and began to die of starvation. This happened in as little as 30 days. Here was the survival curve:

The last guinea pig died after 55 days.

Why did this happen? The guinea pig muscles were damaged by lipid peroxidation leading to cell death. They didn’t have enough antioxidants.

Hill et al didn’t measure muscle thickness, but it wouldn’t surprise me if at 20 days the guinea pigs on their way to an early death had the thickest and most massive quadriceps.

Can Muscle Size Be Used as an Indicator of Overtraining?

If growth in muscle size may indicate muscle damage from either overtraining or antioxidant deficiencies, we might be able to use the response to exercise to assess nutrition or exercise load.

Let’s look again at the Bjørnsen study. If the cross-sectional area of a muscle is proportional to the square of muscle thickness, then we can get a measure of strength per unit cross-section by taking the ratio of leg press 1RM to the square of rectus femoris thickness. That is 1.187/1.109^2 = 0.965 in the antioxidant group, 1.158/1.162^2 = 0.857 in the placebo group. Per unit cross-section, the antioxidant group lost 3.5% in strength, the placebo group lost 14.3%.

It looks like both groups may have damaged their muscles; the antioxidant group just did much less damage. It appears both groups were overtraining relative to their nutritional status. Perhaps if nutrition were better, the response to exercise would have been better, and strength per unit cross-section would have increased. Maybe the missing nutrients included antioxidants, and taking even more antioxidants may have enabled this rigorous training regimen (designed “to stimulate as much muscle growth as possible”) to take place without any impairment of health.

Is Bodybuilding Safe?

If large size can be an indication of damage in muscle, then many techniques which cause muscular hypertrophy will be health-damaging. The healthiest strength gains might come with only small size gains, as the muscle becomes more efficient. It is only unhealthy muscle that becomes super large.

If so, then bodybuilders, who are judged on the size of their muscles, not their strength, will be tempted to use health-damaging and muscle-damaging techniques, like antioxidant deficiencies, to expand their muscle mass. Presumably the winning bodybuilders will be those who use all effective techniques to grow muscle, including the health-damaging ones. So we should expect champion bodybuilders to die young.

I have not seen statistical evidence, but anecdotal lore suggests that champion bodybuilders do, indeed, die young, often of heart diseases (indicating muscle damage). Here are two Youtube videos memorializing bodybuilders who died young:

Conclusion

If you want me to believe that antioxidants are bad, the Bjørnsen study is not going to do it. It looks to me that the elderly men who were in the antioxidant group were the lucky ones. The 1000 mg of vitamin C and 350 IU of vitamin E they were taking daily improved their response to exercise. Indeed, for all we know their antioxidant intake may have been less than optimal!

The elderly men who didn’t get the antioxidants should worry about their hearts. If their leg muscles became large but weak, their hearts may have also.

Everyone who works out should be aware: when it comes to muscles, bigger is not the same as better. The healthiest muscles are those in a wiry physique – modest size, but able to exert a lot of force.

Finally, a pitch for our upcoming October 10-17 Perfect Health Retreat. Our advice is sensible, comprehensive, and increasingly well supported by guest experience. If you want to learn how to optimize health for the rest of your life, and have a great time doing it, please come join us.

References

[1] Bjørnsen T et al. Vitamin C and E supplementation blunts increases in total lean body mass in elderly men after strength training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015 Jul 1. http://pmid.us/26129928.

[2] Hill KE et al. Combined selenium and vitamin E deficiency causes fatal myopathy in guinea pigs. J Nutr. 2001 Jun;131(6):1798-802. http://pmid.us/11385070.

Recent Comments