Erich asked what kind of tea we drink. Tea is a subject dear to our hearts, so we thought we’d discuss it today.

First, some background. Over at Planet Tea they have a useful flowchart describing how different kinds of tea are made:

The critical step is fermentation, which oxidizes the leaf and turns it black. Green tea is unfermented; oolong (wu long) is partially fermented; and black tea (in Asia, “red tea”) is highly fermented. Black tea has a longer shelf life than green tea.

Growing region matters. Mainland China is by far the world’s largest producer of tea, but China is extremely polluted and we would not trust Chinese tea. Japan and Taiwan both produce excellent green teas; we drink tea from both countries.

Taiwanese Tea

The Taiwanese teas with the highest reputation are “high mountain tea”; these are grown at high altitudes above the smog. We drink both green and oolong high mountain teas from Taiwan. Ours come in 300 g vacuum-packed packages:

The one on the left is green tea, the one on the right an oolong; both are “high mountain” teas. Each package weighs 300 g. We use about 4 g (20 leaves) of tea per day, and so a package lasts about 3 months. A single 300 g package of high quality tea may cost $100, so the total cost is about $1 per day; but multiple cups of tea may be obtained from each day’s tea.

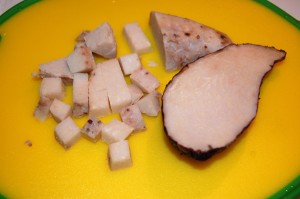

The leaves are rolled and dried during processing, and shrivel to a very small size, then re-expand when placed in warm water. Here is what they look like:

Left — rolled and dried leaves, ready to make tea. Right — an opened bud, after being used.

The opened bud on the right gives you a good idea what the leaves look like on the tea tree. Workers pluck these small buds from the trees and place them in baskets; the finest buds are plucked early in the spring.

Aside: Some Equipment

For best results it’s important to use pure water. Tap water produces a discolored tea with a foul taste. We get good results filtering our water in a Britta filter. In fact, we judge that it’s time to change the filter when our tea changes taste. The Britta instructions recommend changing the filter every two months, but we find it needs to be changed every month if our tea is to retain its flavor.

If you make tea often, it’s helpful to have a hot water dispenser, like this one from Zojirushi, along with your Britta filter:

Tea is best when the leaves have steeped for about 5 minutes. Since you may take much longer to drink the tea, it’s important to steep the tea in a separate container from your drinking mug. Here’s what we use:

Left — An Asian “busy person’s” tea-pot. A container at top holds the tea leaves and enough water to make a single cup. When the leaves are done steeping, pressing the red button drains the water into the pot, after which it can be poured into a mug. Right — an airtight container we use to store our tea leaves.

Alternatively, Asian supermarkets sell teacups in 3 parts — a mug, a container to hold the tea leaves, and a lid to cover while the tea is steeping. They look like this:

The tea leaves go in the removable upper part; when it is removed the tea drains through the holes in the bottom into the mug. After drinking a cup, the upper container with the leaves can be put back in and more hot water added to steep another cup.

Making the Tea

To make the tea, place 15-20 rolled buds into the leaf container, and add hot (near boiling) water. Taiwanese green tea typically requires 3 to 5 minutes to steep, and the tea is actually yellow, not green.

Shou-Ching likes her tea prepared the classic way. Add hot water to new leaves, and drain it after 30 seconds as the leaves just begin to open; this is thought to clean any impurities. Then add new hot water, let it steep 3 to 5 minutes, and drink this second batch. This produces a delicate, light yellow tea. Paul lets his steep a bit longer to make a slightly darker tea and adds a lemon slice. Here is what they look like:

Japanese Green Tea

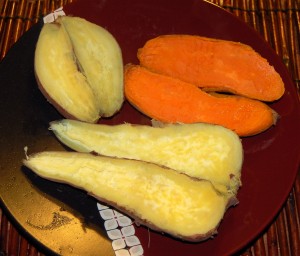

Japanese green tea is made with a different process; the tea leaves are usually crumbled, not rolled. Here is what they look like:

These crumbled tea fragments are placed directly in the teacup and produce a green-colored tea. Yes, the tea leaves can be swallowed. Here is a comparison of a cup of Japanese green tea (left) with a Taiwanese green tea (right):

Obtaining Fine Teas

We are regularly sent tea by relatives and friends in Asia, so we haven’t had to shop for tea in the US.

However, Google searches turn up a number of vendors. “Tea from Taiwan” has some good-looking teas. Reader Gary Wilson kindly wrote to recommend Upton Tea Imports. And here are some Amazon links, not all currently available:

- First Grade Green Tea (Chinese Tea / Taiwanese Tea) – TenRen’s Brand (Free Gift Included – Bloosom Lotus Lucky Knot)

- Oolong Tea-Alishan High Mountain Tea,The Unique Local Climate and The Selection Criteria for Leaves Make Alishan Oolong Tea Rarity. 150g/bag Comes With Beautiful Tin Can.One of The Best Tea in Taiwan You Should Try.

- Taiwanese Tea Sampler (3 Tins) – Jasmine, TiKuanYin (Iron Goddess) & Dong Ting Oolong (Wu Long) Tea (Loose Tea)

At roughly $1 per day, fine tea is not inexpensive. However, many people spend as much or more on coffee. Paul makes 5 or 6 cups per day from a single 4 g set of leaves, so the cost averages to only $0.20 per cup.

If your only knowledge of tea is derived from the Lipton Tea Company, we very much recommend that you give fine green or oolong teas a try! You might find tea more pleasant and enjoyable than you imagined.

Recent Comments