In our last post, Exercise: Is Less Better Than More?, I quoted four studies showing that light aerobic exercise, of the intensity of jogging at 10 or 11 minutes per mile, improved health up to a volume of about 30 minutes per day, but then the health benefits plateau. Light aerobic exercise seems to become unhealthy as the volume exceeds 50 minutes per day.

Today I’ll continue looking at low-level activity to try to clarify where the health benefits come from, so that we can better design a health-maximizing exercise program.

Sitting versus Standing

There seem to be negative health effects from even short periods – a few hours – of inactivity: sitting or lying down.

A recent systematic review, first-authored by TJ Saunders of Obesity Panacea, found that a single day of bed rest is sufficient to raise triglycerides, and that 2 hours of sitting increases insulin resistance and impairs glucose tolerance – moving the body closer to a diabetic phenotype. [1]

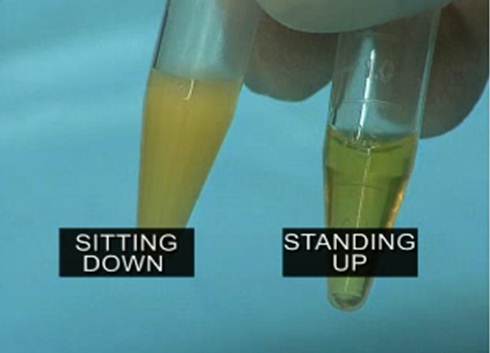

Research by Marc Hamilton found that sitting shuts down expression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in skeletal muscle, preventing muscle cells from importing fat. [2] A Science Daily article shows an interesting video based on this research. Here are blood samples after consumption of an identical meal eaten the same person; the left sample was taken after a meal eaten sitting down, the right sample after a meal eaten standing:

When sitting, dietary fats are taken up only by adipose tissue. When standing, they are taken up by muscle and adipose tissue both.

When sitting, dietary fats are taken up only by adipose tissue. When standing, they are taken up by muscle and adipose tissue both.

Time spent standing did more to push fat into muscle cells than vigorous daily exercise. This is significant because pushing nutrients into muscle cells promotes muscle growth. If you have trouble gaining muscle, maybe the problem is too much sitting, and what you need is not more intense workouts, but more frequent standing!

Sleep Is Good

Not all inactivity is bad, however. Sleep is highly beneficial.

Consequences of poor quality or insufficient sleep include:

- Higher rates of cancer. [3]

- Impaired immunity and vulnerability to infection. [4]

- Higher rates of heart disease. [5]

- Higher all-cause mortality. [6]

- Faster cognitive decline with age. [7]

- Shortening of telomeres. [8]

- Higher rates of diabetes. [9]

One way to interpret this: Inactivity during the day is unequivocally bad, but inactivity at night may be a good thing.

This may be an indication that the benefits of activity come not through fitness, but through entrainment of circadian rhythms. To enhance circadian rhythms, we want daytime activity but night-time rest.

Activity at Work

If activity and exercise at work are good, it might seem a good thing to have an active job. Why not get paid for getting your exercise?

However, the data is not so clear. In comparisons of sedentary work with active work, usually the sedentary workers come out pretty well. For example:

- In women, no relationship was found between occupational physical activity and heart disease risk. [10]

- In the HUNT 2 study, people with metabolic syndrome were more likely to die of cardiovascular disease if their work included physical activity than if it was sedentary. [11]

- In the Copenhagen City Heart Study, high occupational physical activity was associated with higher all-cause mortality. [12]

It seems that when it comes to routine physical activity, more is not better. Exercise is a stressor, and it’s easy to get too much. Being active for eight hours a day is too much.

How Much Activity is Optimal?

If we can easily get too much low-level activity, then what is the optimal amount?

I suggested in my last post that we don’t have an innate “activity reward” system in the brain because our hunter-gatherer ancestors got more exercise than they needed. If that’s true, then we can look to hunter-gatherers to see what constitutes enough activity.

So how much activity did hunter-gatherers get?

It’s been estimated that hunter-gatherers typically walk 5 miles a day, run 1 mile a day, and do various resistance-style carrying and lifting activities. For instance, anthropologist Kim Hill states:

The Ache hunted every day of the year if it didn’t rain. Recent GPS data I collected with them suggests that about 10 km (kilometers) per day is probably closer to their average distance covered during search. They might cover another 1-2 km per day in very rapid pursuit. Sometimes pursuits can be extremely strenuous and last more than an hour. Ache hunters often take an easy day after any particularly difficult day, and rainfall forces them to take a day or two a week with only an hour or two of exercise. Basically they do moderate days most of the time, and sometimes really hard days usually followed by a very easy day. The difficulty of the terrain is really what killed me (ducking under low branches and vines about once every 20 seconds all day long, and climbing over fallen trees, moving through tangled thorns etc.)

The Hiwi on the other hand only hunted about 2-3 days a week and often told me they wouldn’t go out on a particular day because they were “tired”. They would stay home and work on tools etc. Their travel was not as strenuous as among the Ache (they often canoed to the hunt site), and their pursuits were usually shorter. When I hunted with Machiguenga, Yora, Yanomamo Indians in the 1980s, my days were much, much easier than with the Ache. And virtually all these groups take an easy day after a particularly difficult one. [13]

So the Ache walked about 6 miles per day, ran about 1 mile; other groups did less, but all of them traversed more difficult terrain than modern walkers and runners. So it seems that 5 miles of walking and 1 mile of running per day on easy terrain might be a reasonable estimate for the optimal daily activity level.

Five miles is about 10,000 steps. A review of the evidence suggested that 7,000 to 11,000 steps per day achieves all the health benefits of walking. [14]

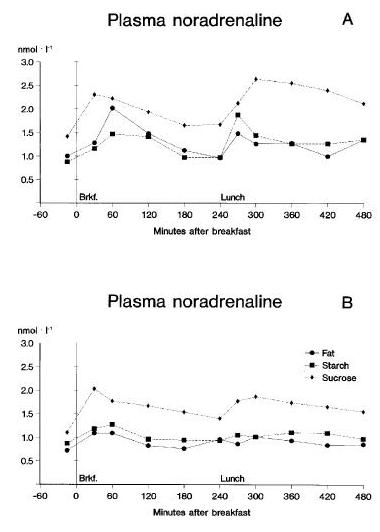

In a comment, Jason gave us a link to a Runner’s World article that contained figures from a recent paper [15]. These illustrate the plateauing of health benefits at a relatively low level of activity:

Above about 30 MET-hours per week of activity, corresponding to 2 hours per week (20 minutes per day) of running at 7 minutes per mile or 4 hours per week (40 minutes per day) of jogging at 10 minutes per mile, there are no health benefits to additional activity.

In other words, the benefits of exercise run out after running 3 miles or jogging 4 miles per day – not far from the hunter-gatherer activity level.

The shape of this curve is supportive of the idea that circadian rhythm enhancement, not fitness, is the cause of the health benefits of exercise. Levels of activity beyond running 20 minutes per day do increase fitness – every cross country or track team in the country trains at a higher level than this – but do not improve health; so health does not depend on fitness. It looks like we need a certain amount of activity to properly entrain our circadian rhythms – to tell our bodies that it is daytime, the time of activity – but once we’ve achieved that, we don’t need to do more.

Centenarians Don’t Over-Exercise

Dan Buettner, author of The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest, has said, “None of the longest-lived societies we studied exercise as we think of it.”

And, based on my readings of centenarian obituaries, it seems true that the longest-lived often don’t do a lot of exercise. A reader who has commented as “B.C.” emailed me a link to a New York Times story on Julia Koo, a centenarian who recently celebrated her 107th birthday in good health. Her secret to a long life: “No exercise, eat as much butter as you like and never look backwards.” [16]

Conclusion

It looks like if we want optimal health, at least four factors should influence our daily activity:

– When it comes to vigorous activites like running, jogging, or lifting, we should do neither too much nor too little. A half hour of such activity per day may be optimal for health, an hour or more may do us more harm than good. Thus, occupations that require physical activity throughout the day may be health impairing.

– Several hours per day of walking is probably beneficial.

– The rest of the day should be restful, but not completely inactive. We should not go more than 20 minutes without standing.

– There are reasons to believe that the benefits of activity may derive more from circadian rhythm entrainment than from fitness. If this is true, then it may be important to develop a routine that includes some activity every day, than it is to optimize fitness by a well designed high-intensity interval training and on-day/off-day protocol.

It really didn’t occur to me until we worked on the new edition of the book that circadian rhythms might be the reason for the health benefits of exercise. (We have more evidence in the book for this idea, including the observations that exercise in the day improves sleep quality at night, and that circadian rhythm disruption has similar health effects to sedentary living.) Since working through this research, I’ve become much more committed to doing something every day – but much less concerned about whether that activity is well designed to make me fit.

References

[1] Saunders TJ et al. Acute sedentary behaviour and markers of cardiometabolic risk: a systematic review of intervention studies. J Nutr Metab. 2012; 2012:712435. http://pmid.us/22754695.

[2] Hamilton MT et al. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes. 2007 Nov;56(11):2655-67. http://pmid.us/17827399.

[3] Nieto FJ et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cancer mortality: results from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Jul 15;186(2):190-4. http://pmid.us/22610391.

[4] Bollinger T et al. Sleep, immunity, and circadian clocks: a mechanistic model. Gerontology. 2010;56(6):574-80. http://pmid.us/20130392.

[5] Hoevenaar-Blom MP et al. Sleep duration and sleep quality in relation to 12-year cardiovascular disease incidence: the MORGEN study. Sleep. 2011 Nov 1;34(11):1487-92. http://pmid.us/22043119.

[6] Cappuccio FP et al. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010 May;33(5):585-92. http://pmid.us/20469800.

[7] Altena E et al. Do sleep complaints contribute to age-related cognitive decline? Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:181-205. http://pmid.us/2107524.

[8] Barceló A et al. Telomere shortening in sleep apnea syndrome. Respir Med. 2010 Aug;104(8):1225-9. http://pmid.us/20430605.

[9] Botros N et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2009 Dec;122(12):1122-7. http://pmid.us/19958890.

[10] Mozumdar A et al. Occupational physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease among active and non-active working-women of North Dakota: a Go Red North Dakota Study. Anthropol Anz. 2012;69(2):201-19. http://pmid.us/22606914.

[11] Moe B et al. Occupational physical activity, metabolic syndrome and risk of death from all causes and cardiovascular disease in the HUNT 2 cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2012 Sep 28. [Epub ahead of print] http://pmid.us/23022656.

[12] Holtermann A et al. Occupational and leisure time physical activity: risk of all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012 Feb 13;2(1):e000556. http://pmid.us/22331387.

[13] O’Keefe JH et al. Exercise like a hunter-gatherer: a prescription for organic physical fitness. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011 May-Jun;53(6):471-9. http://pmid.us/21545934.

[14] Tudor-Locke C et al. How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011 Jul 28;8:80. http://pmid.us/21798044.

[15] Chomistek AK et al. Vigorous-intensity leisure-time physical activity and risk of major chronic disease in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Oct;44(10):1898-905. http://pmid.us/22543741.

[16] James Barron, “Lessons of 107 Birthdays: Don’t Exercise, Avoid Medicine and Never Look Back,” The New York Times, September 24, 2012, http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/24/lessons-of-107-birthdays-dont-exercise-avoid-medicine-and-never-look-back/.

Recent Comments