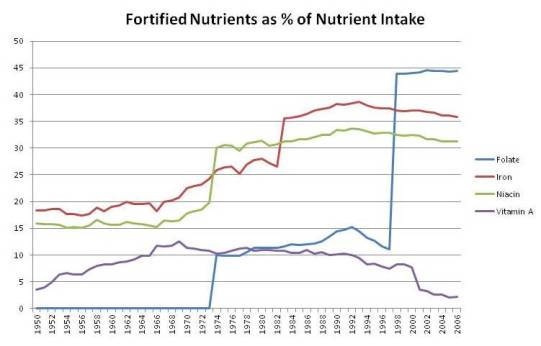

In Food Fortification: A Risky Experiment?, Mar 23, 2012, we began looking at the possibility that fortification of food, especially the enriched flours used in commercial baked goods, with niacin, iron, and folic acid may have contributed to the obesity and diabetes epidemics.

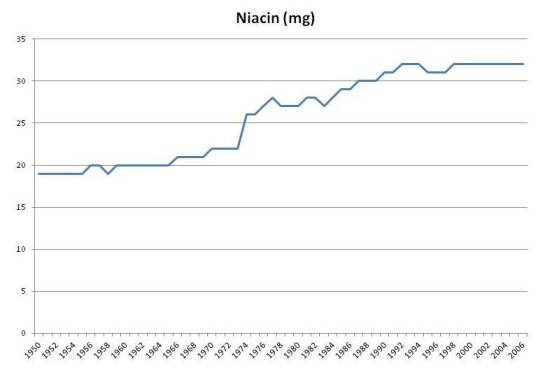

As this plot shows, fortification caused intake of per capita niacin intake in the United States to rise from about 20 mg/day to about 32 mg/day:

Multivitamins typically contain about 20 mg niacin, so (a) a typical American taking a multivitamin is getting 52 mg/day niacin, and (b) if the increase of 12 mg/day due to fortification is dangerous, then taking a multivitamin would be problematic too.

There wasn’t evidence of niacin deficiency at 20 mg/day. The RDA was set at 16 mg/day for men and 14 mg/day, levels that equalize intake with urinary excretion of niacin metabolites [source: Dietary Reference Intakes]. Fortification of grains with niacin was designed to make refined white wheat have the same niacin content as whole wheat, not to rectify any demonstrated deficiency of niacin.

B-vitamins are normally considered to have low risk for toxicity, since they are water soluble and easily excreted. But recently, scientists from Dalian University in China proposed that niacin fortification may have contributed to the obesity and diabetes epidemics. [1] [2]

Niacin, Oxidative Stress, and Glucose Regulation

The Chinese researchers note that niacin affects both appetite and glucose metabolism:

[N]iacin is a potent stimulator of appetite and niacin deficiency may lead to appetite loss [10]. Moreover, large doses of niacin have long been known to impair glucose tolerance [23,24], induce insulin resistance and enhance insulin release [25,26].

They propose that niacin’s putative negative effects may be mediated by oxidative stress, perhaps compounded by poor niacin metabolism:

Our recent study found that oxidative stress may mediate excess nicotinamide-induced insulin resistance, and that type 2 diabetic subjects have a slow detoxification of nicotinamide. These observations suggested that type 2 diabetes may be the outcome of the association of high niacin intake and the relative low detoxification of niacin of the body [27].

The effect of niacin on glucose metabolism is visible in this experiment. Subjects were given an oral glucose tolerance test of 75 g glucose with or without 300 mg nicotinamide. [1, figure source]

Dark circles are from the OGTT with niacinamide, open circles without. Plasma hydrogen peroxide levels, a marker of oxidative stress, and insulin levels were higher in the niacinamide group. Serum glucose was initially slightly higher in the niacinamide group, but by 3 hr had dropped significantly, to the point of hypoglycemia in two subjects:

Two of the five subjects in NM-OGTT had reactive hypoglycemia symptoms (i.e. sweating, dizziness, faintness, palpitation and intense hunger) with blood glucose levels below 3.6 mmol/L [64 mg/dl]. In contrast, no subjects had reactive hypoglycemic symptoms during C-OGTT. [1]

Of course 300 mg is a ten-fold higher niacinamide dose than most people obtain from food, but perhaps chronic intake of 32 mg/day (52 mg/day with a multivitamin) daily over a period of years have similar cumulative effects on glucose tolerance as a one-time dose of 300 mg.

Is There a Correlation with Obesity?

OK. Is there an observable relationship between niacin intake and obesity or diabetes?

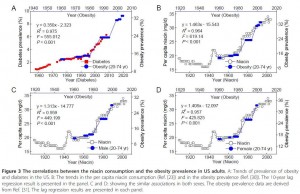

There may be, but only with a substantial lag. Here is a figure that illustrates the possible connection [2, figure source]:

Niacin intake maps onto obesity rates with a 10-year lag. After niacin intake rose, obesity rates rose 10 years later. Note the scaling: a 60% increase in niacin intake was associated with a doubling of obesity rates 10 years later.

Obesity leads diabetes by about 15 years, so we could also get a strong correlation between niacin intake and diabetes incidence 25 years later. The scaling in this case would be a 35% increase in niacin associated with a 140% increase in diabetes prevalence after a lag of 25 years.

How seriously should we take this? As evidence, it’s extremely weak. There was a one-time increase in niacin intake at the time of fortification. A long time later, there was an increase in obesity, and long after that, an increase in diabetes. So we really have only 3 events, and given the long lag times between them, the association between the events is highly likely to be attributable to chance.

It was to emphasize the potential for false correlations that I put the stork post up on April 1 (Theory of the Stork: New Evidence, April 1, 2012). Just because two data series can be made to line up, with appropriate scaling of the vertical axis and lagging of the horizontal axis, doesn’t mean there is causation involved.

Is There Counter-Evidence?

Yes.

If niacin from wheat fortification is sufficient to cause obesity or diabetes, with an average intake of 12 mg/day, then presumably the 20 mg of niacin in multivitamins would also cause obesity or diabetes.

So we should expect obesity and diabetes incidence to be higher in long-time users of multivitamins or B-complex vitamins.

But in fact, people who take multivitamins or B-complex vitamins have a lower subsequent incidence of obesity and diabetes.

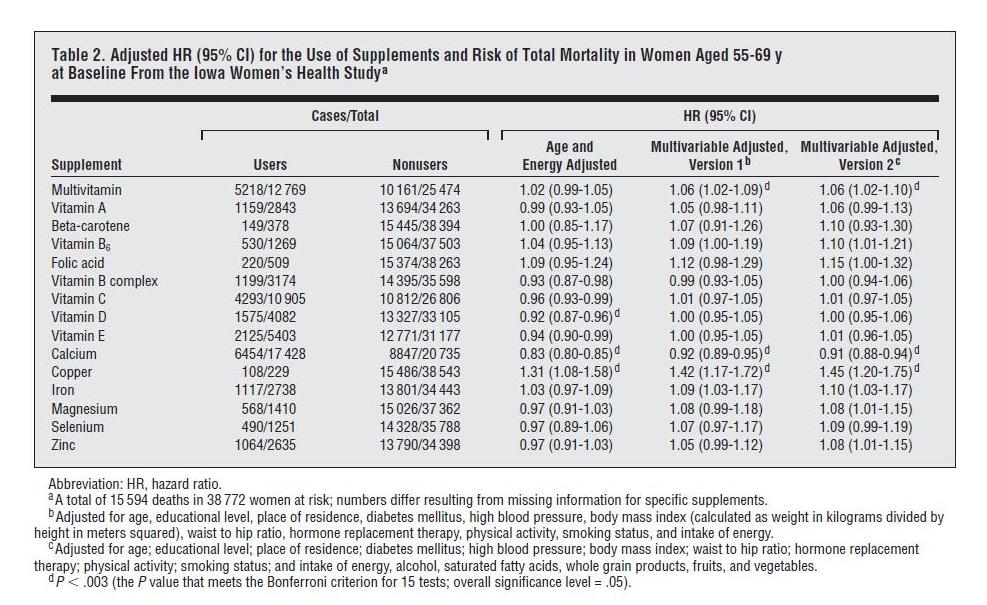

One place we can see this is in the Iowa Women’s Health Study, discussed in a previous post (Around the Web; The Case of the Killer Vitamins, Oct 15, 2011). In that post I looked at a study analysis which was highly biased against vitamin supplements; the authors chose to do 11-factor and 16-factor adjustments designed to make supplements look bad. The worst part of the analysis, from my point of view, was using obesity and diabetes as adjustment factors in the regression analysis. As you can see in the table below, multivariable adjustment including obesity and diabetes significantly raises the mortality associated with consumption of multivitamins or B-complex supplements:

This increase in hazard ratios (“HR”) with adjustment for obesity and diabetes almost certainly indicates that the supplements reduce the incidence of these diseases.

Multivitamins are protective in other studies too. The relation between multivitamin use and subsequent incidence of obesity was specifically analyzed in the Quebec Family Study, which found that “nonconsumption of multivitamin and dietary supplements … [was] significantly associated with overweight and obesity in the cross-sectional sample.” [3]

Does this exculpate niacin supplementation? I don’t think so. In general, improved nutrition should reduce appetite, since the point of eating is to obtain nutrients. So it’s no surprise that multivitamin use reduces obesity incidence. But multivitamins contain many nutrients, and it could be that benefits from the other nutrients are concealing long-term harms from the niacin.

Conclusion

At this point I think the evidence against niacin is too weak to convict in a court of law.

Nevertheless, we do have:

- Clear evidence that high-dose (300 mg) niacinamide causes oxidative stress and impaired glucose tolerance. If niacinamide can raise levels of peroxide in the blood, what is it doing at mitochondria?

- No clear evidence for benefits from niacin fortification or supplementation.

Personally I see no clear evidence that niacin supplementation, even at the doses in a multivitamin, is likely to be beneficial. Along with other and stronger considerations, this is pushing me away from multivitamin use and toward supplementation of specific individual micronutrients whose healthfulness is better attested.

I also think that food fortification was a risky experiment with the American people, and stands as yet another reason to avoid eating grains and grain products. (And to rinse white rice before cooking, to remove the enrichment mixture.)

References

[1] Li D et al. Chronic niacin overload may be involved in the increased prevalence of obesity in US children. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 May 21;16(19):2378-87. http://pmid.us/20480523.

[2] Zhou SS et al. B-vitamin consumption and the prevalence of diabetes and obesity among the US adults: population based ecological study. BMC Public Health. 2010 Dec 2;10:746. http://pmid.us/21126339.

[3] Chaput JP et al. Risk factors for adult overweight and obesity in the Quebec Family Study: have we been barking up the wrong tree? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009 Oct;17(10):1964-70. http://pmid.us/19360005.

Recent Comments