Jimmy Moore is graciously continuing the conversation about safe starches with a post from Dr Ron Rosedale. For those trying to keep track, here’s how the discussion has gone:

- Jimmy’s original seminar on safe starches, featuring Paleo and low-carb luminaries.

- My main reply appeared both here and at Jimmy’s. I also wrote further on how to minimize hyperglycemic toxicity, and offered an appreciation of Dr Kurt Harris.

- Now, Dr Ron Rosedale has replied to my reply.

Today, I’ll reply to Dr Rosedale.

Dr Rosedale argues that glucose is toxic, so we should want to have less of it in our bodies; and that low-carb diets deliver less of it. He cites a lot of papers on the relationship between blood glucose levels and health, and uses blood glucose levels as a proxy for the level of glucose in the body.

Two basic matters are at issue: (1) What blood glucose level is best for health? (2) Which diet will generate those optimal blood glucose levels?

Let’s look at what the evidence shows.

What Blood Glucose Level is Best for Health?

In my main reply, I had written:

What is a dangerous level of blood glucose?

In diabetics, there seems to be no detectable health risk from glucose levels up to 140 mg/dl, but higher levels have risks. Neurons seem to be the most sensitive cells to high glucose levels, and the severity of neuropathy in diabetes is correlated with how high blood glucose rises above 140 mg/dl in response to a glucose tolerance test. [1] In people not diagnosed with diabetes, there is also some evidence for risks above 140 mg/dl. [2]

Dr Rosedale seemed to feel that this was the weakest point in my argument, and directed his fire here. My statement was a description of what the scientific literature shows, and the adjective “detectable” carries a lot of weight here. To refute my statement, you would have to find study subjects whose blood glucose never goes above 140 mg/dl, and yet show health impairments attributable to glucose.

Dr Rosedale argues there is no threshold separating safe from harmful levels of glucose, because glucose acts as a toxin at all concentrations:

I will spend a fair amount of time and show a fair number of studies to show that there is no threshold. Very simply, the higher the blood sugar rise, the more damage is done in some linear upward slope.

I emailed Ron to make sure that he really did mean there was no threshold, so that glycemic toxicity begins at 0 mg/dl. He replied:

I mean the former; that glucose will cause some damage when above 0 mg/dl … obviously a moot point and theoretical when glucose very low and incompatible with life and likely a minute amount of damage when that low. At any level of glucose compatible with life some more meaningful degree of glycation, hormonal response and genetic expression will take place. We will always want/need to repair the damage done to stay alive, but with age the repair mechanisms become damaged also. Eventually damage outdoes repair and we “age”, acquire chronic disease, and die.

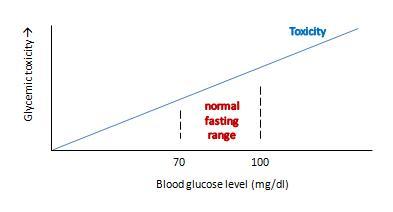

Ron’s view can be graphed like this:

This view makes sense as a matter of molecular chemistry: the number of glycation reactions may be proportional to the concentration of glucose, and if glycation products are health damaging toxins then toxicity may be proportional to glucose levels.

The trouble with this is that it doesn’t really get at what we want to know: what blood glucose level optimizes human health?

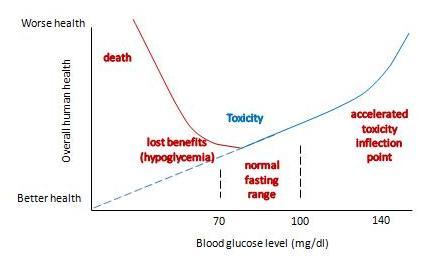

If we change the y-axis so that it doesn’t measure glycemic toxicity, but rather overall health of the human organism, then the shape of the curve is going to change in two major ways:

- First, in translating toxicity to its impact on health, we have to account for Paracelsus’s rule: “the dose makes the poison.” The body can readily repair small doses of a toxin with no ill effect – possibly even a hormetic benefit – but large doses of a toxin multiply damage exponentially and can prove fatal. So the impact of a toxin on health will not rise linearly, but non-linearly with a steeper slope as one moves to the right.

- Second, we have to account for the fact that glucose has a role as a nutrient. As Ron himself says, having too little blood glucose is “incompatible with life.” So low blood glucose – depriving us of the benefits of normal levels of this nutrient – is a catastrophic negative for health. This means that the left side of the curve needs radical adjustment.

With these two changes, our graph becomes something like this:

It now has a U-shape. I’ve drawn the inflection point where toxicity starts rising rapidly at around 140 mg/dl, and the inflection point on the other side where hypoglycemia causes substantial health damage at around 60 mg/dl. But the precise numbers don’t matter much; the point is that there is a U-shape, and somewhere in that U is a bottom where health is optimized.

What do we know about the precise shape of that U, and the location of the bottom?

We can’t intuit the shape of the bottom of the U using theoretical speculations. Theory doesn’t allow us to balance risks of hypoglycemia against toxicity on such a fine scale. The bottom of the U could be very flat, and it might not matter much whether blood glucose levels are 80 or 100 mg/dl. Or the bottom of the U could be tilted, so that the optimum is either at the low end, near 80 mg/dl, or the high end, near 100 mg/dl.

Empirical evidence is limited. Most studies relating blood glucose levels to health have been done on diabetics eating high-carb diets. There are few studies on healthy people, very few testing low-carb diets, and most are insufficiently powered to determine the precise shape of the bottom of the U.

Dr. Rosedale cites a good selection of studies in his response, and let’s review a representative subset. I was familiar with most of the studies; indeed some were cited in our book’s discussion of the dangers of hyperglycemia.

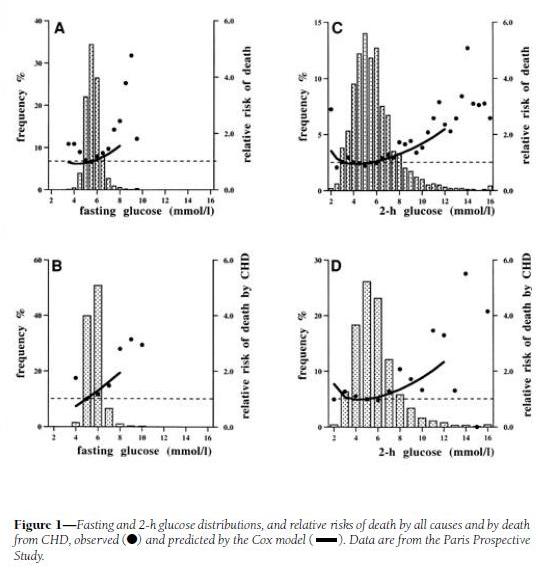

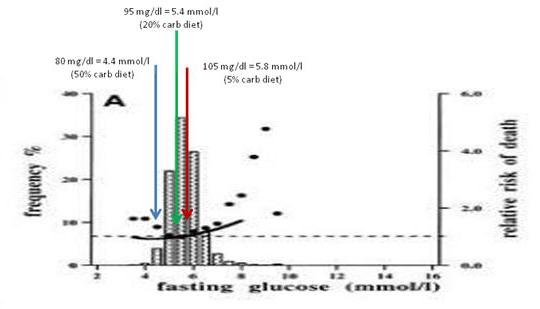

His first cite is “Is there a glycemic threshold for mortality risk?” from Diabetes Care, May 1999, http://pmid.us/10332668. Here is their data:

Look at the black dots, which are the actual data, not the fitted curves which are model-dependent; and at panels A and C, which treat all-cause mortality, not B and D, which are specific for coronary heart disease.

For both fasting and 2-h postprandial blood glucose, the black dots are lowest between about 4.5 and 6.0 mmol/l, which translates to 81 to 108 mg/dl. However, note that there is very little rise in mortality – only about 10% higher relative risk – in 2-h glucose levels of 7 mmol/l, which is 126 mg/dl. Since the postprandial peak is rarely at 2-h (45 min is a common peak), most of these people may well have been experiencing peak levels above 140 mg/dl.

My interpretation: I would say that this study demonstrates that mortality is a U-shaped function of blood glucose levels, but it doesn’t tell us the shape of the bottom of the U. It is consistent with the idea that significant health impairment occurs only with excursions of blood glucose above 140 mg/dl or below 60 mg/dl.

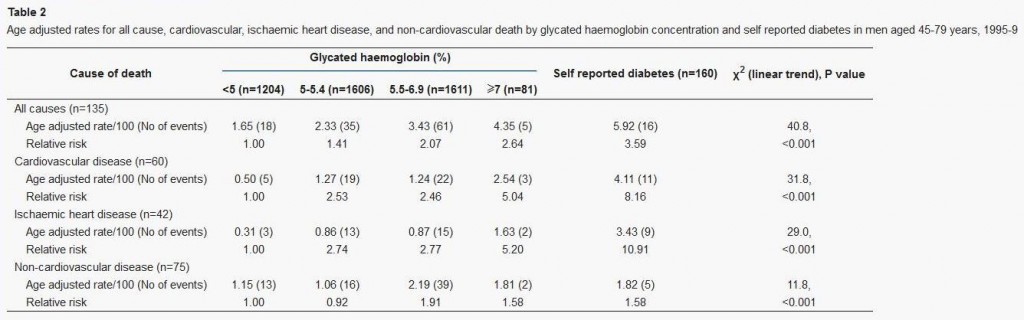

Dr Rosedale’s second cite is actually to a commentary: “‘Normal’ blood glucose and coronary risk” in the British Medical Journal, http://pmid.us/11141131, commenting on a paper by Khaw et al, “Glycated haemoglobin, diabetes, and mortality in men in Norfolk cohort of european prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition (EPIC-Norfolk),” http://pmid.us/11141143.

This study used glycated hemoglobin, HbA1c, which can serve as a measure of average blood glucose over the preceding ~3 weeks. Here is the data:

This supports the “blood sugar should be as low as possible” thesis, since lower HbA1c levels were associated with lower mortality. However, this study has a few flaws:

- It includes diabetics. Diabetics have poor glycemic control, and episodes of hypoglycemia as well as hyperglycemia, so HbA1c levels (which represent average blood sugar levels) may be a poor proxy for the levels of glycemic toxicity. Also, diabetics are usually on blood-glucose lowering medication, which may distort the blood sugar – mortality relationship.

- It lumps the population together in very large cohorts. Effectively there were only three cohorts, since the highest HbA1c cohort had only 2% of the sample; the other three cohorts contained 27%, 36%, and 36% of the study population respectively.

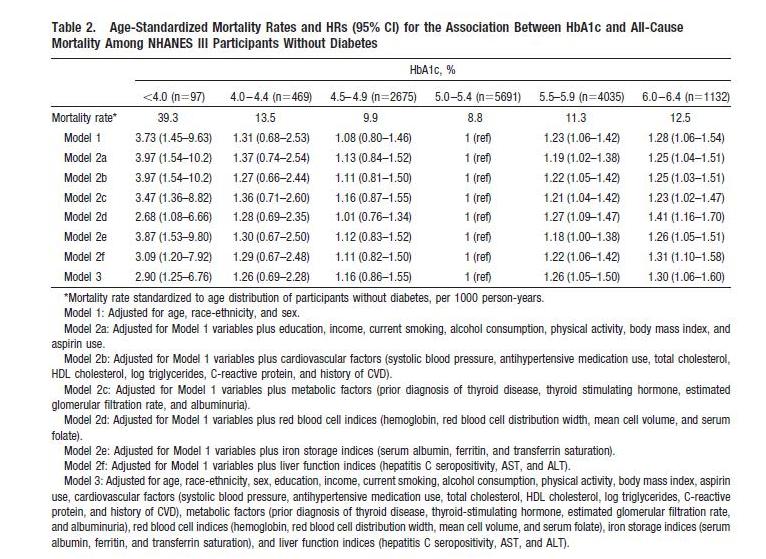

We can get a finer grip on what happens by looking at studies that lack these flaws. Here’s one: “Low hemoglobin A1c and risk of all-cause mortality among US adults without diabetes,” Circulation, 2010, http://pmid.us/20923991.

This study is an an analysis of NHANES III; it excludes diabetics and has 3 cohorts, not 1, with HbA1c below 5%. Here’s their data:

The U-shaped mortality curve is very clear. In raw data and all models, the lowest mortality is with HbA1c between 5.0 and 5.4. Mortality increases with every step down in HbA1c: in Model 1, mortality is 8% higher with HbA1c between 4.5 and 4.9, 31% higher between 4.0 and 4.4, and 273% higher below 4.0.

Via Ned Kock of Health Correlator comes a formula for translating HbA1c to average blood glucose levels:

Average blood glucose (mg/dl) = 28.7 × HbA1c – 46.7

Average blood glucose (mmol/l) = 1.59 × HbA1c – 2.59

So the minimum mortality HbA1c range of 5.0 to 5.4 translates to an average blood glucose level of 96.8 to 108.3 mg/dl (5.36 to 6.00 mmol/l).

This result is almost identical to the finding in Dr Rosedale’s first cite, from which Dr Rosedale quoted: “the lowest observed death rates were in the intervals centered on 5.5 mmol/l [99mg/dl] for fasting glucose.”

My interpretation: Once again, we find that there is a U-shaped mortality curve, and minimum mortality occurs with average or fasting blood glucose in the middle of the normal range – in the vicinity of 100 mg/dl or 5.5 mmol/l.

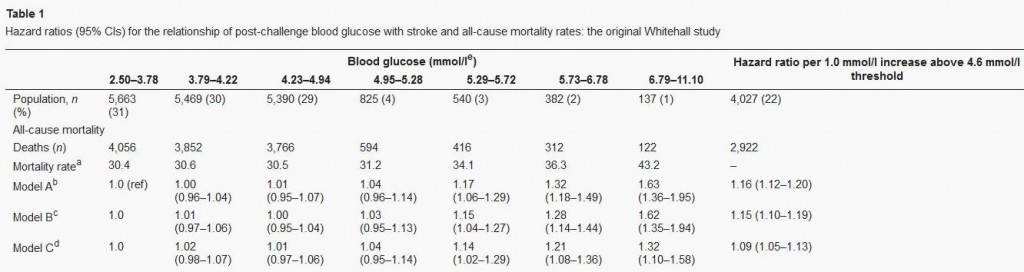

Let’s finish our examination of this issue with a quick look at Dr Rosedale’s third cite. That paper, “Post-challenge blood glucose concentration and stroke mortality rates in non-diabetic men in London: 38-year follow-up of the original Whitehall prospective cohort study,” Diabetologia, http://pmid.us/18438641, is a familiar one; it was cited in our book (p 36, fn 35).

This study looked at blood glucose levels 2 hours after swallowing 50 grams of glucose, and then followed the men for 38 years to observe mortality rates. CarbSane makes an important observation: this study used whole blood rather than plasma to assay blood glucose. Whole blood has more volume (due to inclusion of cells) but the same glucose, and so less glucose per deciliter. According to this paper, standard (plasma) values are about 25 mg/dl higher, so 95 mg/dl in whole blood actually corresponds to a plasma value of about 120 mg/dl.

Here is the data:

There is no significant difference in mortality among any group with post-challenge whole blood glucose up to 5.29 mmol/l (95 mg/dl), corresponding to 120 mg/dl or 6.7 mmol/l in standard measurements.

The study was designed to look at high blood glucose levels: there were 4 cohorts in the top 10% of blood glucose levels, but the bottom cohort in blood glucose had fully 31% of the sample. This cohort consisted of everyone with 2-hr whole blood glucose levels below 68 mg/dl, or plasma glucose below about 90 mg/dl. Mortality in this large group was indistinguishable from that in the next two groups, who had plasma glucose between 90 and 120 mg/dl.

My interpretation: This study wasn’t designed to observe the lower end of the U. At the higher end, it is consistent with the other studies: mortality rises with 2-hr plasma glucose above 120 mg/dl.

Summary: Optimal Blood Glucose Levels

All of the papers cited by Dr Rosedale are consistent with this story:

- Mortality and health have a U-shaped relationship with blood glucose.

- Optimum health occurs at blood glucose levels around 100 mg/dl – at normal levels, not exceptionally low levels.

- The impaired health seen with fasting or 2-hr blood glucose levels of 110 or 120 mg/dl may be largely attributable to the portion of the day in which those people experience blood glucose levels over 140 mg/dl.

I should note that Dr Rosedale acknowledges that high-normal blood glucose is better than low blood glucose for some aspects of health, like fertility:

Safe starch proponents say that raising blood glucose and raising insulin is a very natural phenomenon and needn’t be avoided. However, if we evolved in a certain way and with certain physiologic responses to the way we eat, it was not for a long, healthy, post-reproductive lifespan. It was for reproductive success. The two are not at all synonymous, in fact often antagonistic.

He’s saying that higher blood glucose favors “reproductive success,” while lower blood glucose favors “post-reproductive lifespan.” I guess one has to choose one’s priorities. Not everyone will choose maximum lifespan.

But suppose Dr Rosedale is right, and that low blood glucose levels are most desirable for at least some persons. I’m willing to stipulate, for the sake of argument, that optimal health for some persons may occur at below-normal blood glucose levels – say, 80 mg/dl. That brings us to the second issue: which diet will produce these low blood glucose levels?

Which Diet Minimizes Blood Glucose Levels?

If the key to health is achieving below-normal blood glucose levels, then low-carb diets are in trouble.

In general, very low-carb diets tend to raise fasting blood glucose and 2-hr glucose levels in response to an oral glucose tolerance test.

This is a well-known phenomenon in the low-carb community. When I ate a very low-carb diet, my fasting blood glucose was typically 104 mg/dl. Peter Dobromylskyj of Hyperlipid has reported the same effect: his fasting blood glucose is over 100 mg/dl. From one of Peter’s posts:

Back in mid summer 2007 there was this thread on the Bernstein forum. Mark, posting as iwilsmar, asked about his gradual yet progressively rising fasting blood glucose (FBG) level over a 10 year period of paleolithic LC eating. Always eating less than 30g carbohydrate per day. Initially on LC his blood glucose was 83mg/dl but it has crept up, year by year, until now his FBG is up to 115mg/dl….

I’ve been thinking about this for some time as my own FBG is usually five point something mmol/l whole blood. Converting my whole blood values to Mark’s USA plasma values, this works out at about 100-120mg/dl.

Peter notes that low-carb dieters will generally perform poorly on glucose tolerance tests, but that increasing carb intake to about 30% of calories is sufficient to produce a normal response to a glucose challenge:

The general opinion in LC circles is that you need 150g of carbohydrate per day for three days before an oral glucose tolerance test.

This is at the high end of the 20% to 30% of energy (400 to 600 calories on a 2000 calorie diet) that is the Perfect Health Diet recommendation for carbs.

The Kitavans eat more than 60% of calories as carbohydrate, mostly from starches. Their fasting blood glucose averages 3.7 mmol/l (67 mg/dl) (http://pmid.us/12817903).

Studies confirm that high-carb diets tend to lower fasting glucose and to lower the blood glucose response to a glucose challenge. CarbSane forwarded me some illustrative studies:

- “High-carbohydrate, high-fiber diets increase peripheral insulin sensitivity in healthy young and old adults,” http://pmid.us/2168124. Switching healthy adults to a higher carb diet reduced fasting blood glucose from 5.3 to 5.1 mmol/L (95.5 to 91.9 mg/dl) and reduced fasting insulin from 66 to 49.5 pmol/l.

- “Effect of high glucose and high sucrose diets on glucose tolerance of normal men,” http://pmid.us/4707966. On diets with glucose as the only carb source, 2-hr plasma glucose after a glucose challenge was 184 mg/dl on a 20% carb diet, 183 mg/dl on a 40% carb diet, 127 mg/dl on a 60% carb diet, and 116 mg/dl on an 80% carb diet. The 80% carb diet was the only one on which blood glucose never went above 140 mg/dl.

This last study did not report fasting glucose, but did track blood glucose for 4 hours after the glucose challenge. If we take the 4-hr blood glucose reading as representative of fasting glucose, we find that dieters eating 60% or 80% carb diets had fasting glucose of 76 and 68 mg/dl, respectively.

My interpretation of the evidence from multiple sources: A plausible conclusion is that a high-carb diet produces a low fasting glucose (let’s say, 80 mg/dl), a PHD type 20% carb diet an intermediate fasting glucose (95 mg/dl), and a very low-carb diet a high fasting glucose (say, 105 mg/dl).

Just for fun, I decided to see where these fasting glucose levels show up on the mortality plot from Balkau et al:

The 20% carb diet lines up pretty well with the mortality minimum, and both high-carb and very low-carb diets wind up at bins with slightly elevated mortality.

Now, I don’t believe we can infer from data on high-carb dieters what the relationship between blood glucose levels and mortality will be in low-carb dieters. It was Dr Rosedale, not me, who introduced this study into evidence.

But if we believe that lowest mortality really does occur with 2-hr post-challenge blood glucose around 100 mg/dl and fasting blood glucose below 100 mg/dl, as argued by the studies Dr Rosedale cited, and that this result applies to low-carb dieters, then I think the evidence is clear. One must eat some carbohydrates – at least 20-30% of energy.

This is the standard Perfect Health Diet recommendation. It seems that Dr Rosedale is supporting my diet, not his!

What About Diabetics?

Perhaps the boldest passage in Dr Rosedale’s reply was this:

We are all metabolically damaged to some extent. None of us has perfect insulin and leptin sensitivity…. It is for that reason that I say that we all have diabetes, some more than others, and should all be treated as such.

Well, if we all have diabetes, more or less, then I guess I have to consider whether our regular diet – which recommends about 20% of energy (400 calories) as carbs – is healthy for diabetics.

Now, before I begin this discussion, let me say that I don’t claim that this is optimal for diabetics. I think it is still an open question what the optimal diet for diabetics is, and different diabetics may experience a different optimum. I have often said that diabetics may benefit from going lower carb (and possibly higher protein) than our regular dietary recommendations. However, Dr Rosedale is here saying that even a healthy non-diabetic should eat a diet that is appropriate for diabetics. I want to see whether our regular diet meets that standard.

How do diabetics do on a 20% carb diet? Here’s some data that I found in a post by Stephan Guyenet at Whole Health Source. It’s from a 2004 study by Gannon & Nuttall (http://pmid.us/15331548) and the graph is from a later paper by Volek & Feinman (http://pmid.us/16288655/). Over a 24 hour period, blood glucose levels were tracked in Type II diabetics on their usual diets (blue and grey triangles) and after 5 weeks on a 55% carb – 15% protein – 30% fat (yellow circles) or 20% carb – 30% protein – 50% fat diet (blue circles):

The low-carb diet was a little higher in protein and lower in fat than we would recommend, but very close overall to our recommendations and spot-on in carbs.

What happened to blood glucose? It came close to non-diabetic levels. Fasting blood glucose dropped to 7 mmol/l (126 mg/dl), roughly the level at which diabetes is diagnosed. Postprandial blood glucose elevations were modest – peaking below 160 mg/dl which is about 20 mg/dl higher than in normal persons. Average daily blood glucose looks to be around 125 mg/dl.

What would have happened on a zero-carb diet? Fasting blood glucose probably would still have been elevated, near 126 mg/dl; this is common in diabetics because the loss of pancreatic beta cells creates a glucagon/insulin imbalance that leads to elevated fasting blood glucose. This blood glucose level would have been maintained throughout most of the day, with the postprandial peaks and troughs flattening. Average daily blood glucose level would have been similar to that on the 20% carb diet.

So the big benefit, in terms of glycemic control for diabetics, comes from reducing carbs from 55% to 20%. Further reductions in carb intake do not reduce average 24 hour blood glucose levels, but may reduce postprandial glucose spikes.

In fact, we have some Type II diabetics eating Perfect Health Diet style. Newell Wright reports good results:

I am a type II diabetic and a Perfect Health Diet follower, so I want to chime in with my experience….

I switched from the Atkins Induction diet to the Perfect Health Diet. I have been eating rice, potatoes, bananas, and other safe starches ever since, as well as fermented dairy products, such as plain, whole milk yogurt. I have also slowly lost another seven pounds. I enthusiastically recommend the book, Perfect Health Diet by Paul and Shou-Ching Jaminet.

Today, my fasting blood glucose reading was 105. Note that since following the Perfect Health Diet, my fasting blood glucose reading has gone down. Previously, I was suffering from the “dawn phenomenon.” My blood glucose levels overall were well below 140 one hour after a meal and 120 two hours after a meal. Only my fasting BG reading was out of whack, usually between 120 and 130, first thing in the morning.

For dinner tonight, I had a fatty pork rib, green beans, and a small baked potato with butter and sour cream. For dessert, I had a half cup of vanilla ice cream. One hour after eating, my blood glucose level was 128 and two hours after, it was 112.

So not only am I losing weight on the Perfect Health Diet, my blood glucose levels have actually improved, thanks to the increased carbs counteracting the dawn phenomenon, just as Dr. Kurt Harris (another proponent of safe starches) said it would.

So for me, as a type II diabetic, this “safe starches” exclusion is pointless…. [D]espite the type II diabetes, I am doing just fine on the Perfect Health Diet, thank you. I reject the diabetic exclusion of safe starches.

Note that Newell’s fasting blood glucose went down from 125 to 105 mg/dl when he raised his carb intake from Atkins Induction to Perfect Health Diet levels, and postprandial glucose levels on PHD were no higher than his fasting levels on Atkins Induction. It looks like he reduced blood glucose levels by adding starches to his diet.

To repeat: I’m not claiming that our regular diet, providing 20% of energy from “safe starches,” is optimal for diabetics. I don’t know what the optimal diabetes diet is, and it may be different for different diabetics. But I think there is plentiful evidence that even for diabetics, our “regular” diet is not a bad diet. And for some, it might be optimal.

Summary: Putting It All Together

It looks like 20% of energy is a sort of magic number for carbs. It:

- Averts glucose deficiency symptoms while achieving normal insulin sensitivity and glycemic control on oral glucose tolerance tests;

- Avoids significant hyperglycemic toxicity even in diabetics.

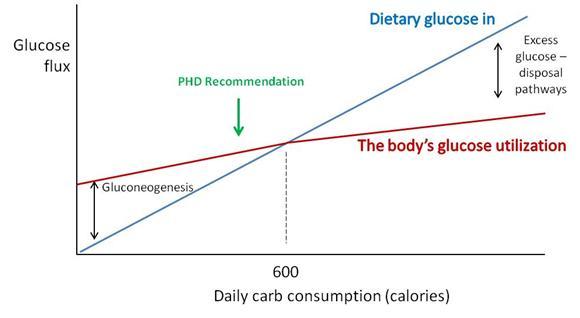

Why does this magic number, which happens to be the Perfect Health Diet recommendation for carb intake, do so well?

Perhaps a chart will make the science a little clearer.

“Dietary glucose in” (blue) represents the amount of carbs obtained from diet. “The body’s glucose utilization” (maroon) is how much glucose will be put to useful purposes at a given daily carb consumption. Glucose utilization does not vary as strongly as glucose intake; at low intakes a deficit is made up by gluconeogenesis (manufacture of glucose from protein) and at high intakes an excess of glucose is destroyed by thermogenesis or conversion of glucose to fat.

Where the blue and maroon lines cross, dietary glucose in matches the body’s glucose utilization. For most sedentary adults, this level will be around 600 carb calories per day. We recommend eating close to or slightly below this point (“PHD Recommendation”).

There are dangers in straying too far from this intersection point:

- Eating too few carbs creates a risk of health impairment due to insufficient glucose or protein.

- Eating too many carbs results in unnecessary exercise of glucose disposal pathways, and possible unhealthy fluctuations in blood glucose levels if those disposal pathways fail.

Hitting just below the intersection is a safe, low-stress point which will work well for most people.

For diabetics, the excess glucose disposal pathways are broken. However, this is not a major problem if you have no excess glucose to dispose of. Eating up to 20% of calories from carbs doesn’t require the use of disposal pathways – glucose can be stored as glycogen and then released as needed, so the effect of dietary glucose is primarily to reduce the amount of gluconeogenesis. Suppressing gluconeogenesis requires some residual insulin secretion ability, so Type I diabetics cannot achieve this, but most Type IIs can.

The upshot: A 20% carb diet meets the body’s glucose needs without much risk of hyperglycemic toxicity even in diabetics.

The Issue of Thyroid Hormones and Anti-Aging

The most distinctive element of Dr. Rosedale’s diet is its emphasis on longevity as the supreme measure of health, and its emphasis on calorie restriction (especially, carb and protein restriction) and metabolic suppression as the means to long life.

Our book, Perfect Health Diet, relied strongly on evidence from evolutionary selection to guide us toward the optimal diet.

Dr. Rosedale rejects evolutionary selection as a helpful criterion, since evolution did not necessarily select for longevity:

[I]f we evolved in a certain way and with certain physiologic responses to the way we eat, it was not for a long, healthy, post-reproductive lifespan. It was for reproductive success. The two are not at all synonymous, in fact often antagonistic. We have no footsteps to follow as far as the best way to eat for long healthy post reproductive life. We can only use the best science pertaining to the biology of aging and apply it to proper nutrition. That is what I feel I am doing.

We actually share much of Dr Rosedale’s perspective on what influences longevity; it is for longevity that we recommend slightly under-eating carb and protein compared to what evolution selects for. However, we don’t go as far in that direction as Dr Rosedale does.

We have written of the suppression of T3 thyroid hormone levels which is part of the body’s strategy for conserving glucose in times of scarcity, and how this is a risk factor for “euthyroid sick syndrome.” See Carbohydrates and the Thyroid, Aug 24, 2011.

Dr Rosedale acknowledges this and believes it to be beneficial:

I believe that Jaminet and most others misunderstand the physiologic response to low glucose, and the true meaning of low thyroid. Glucose scarcity (deficiency may be a misnomer) elicits an evolutionary response to perceived low fuel availability. This results in a shift in genetic expression to allow that organism to better survive the perceived famine…. As part of this genetic expression, and as part and parcel of nature’s mechanism to allow the maintenance of health and actually reduce the rate of aging, certain events will take place as seen in caloric restricted animals. These include a reduction in serum glucose, insulin, leptin, and free T3.

The reduction in free T3 is of great benefit, reducing temperature, metabolic damage and decreasing catabolism…. We are not talking about a hypothyroid condition. It is a purposeful reduction in thyroid activity to elicit health. Yes, reverse T3 is increased, as this is a normal, healthy, physiologic mechanism to reduce thyroid activity.

Note that Dr Rosedale acknowledges that his glucose-scarce diet reduces body temperature. Many Rosedale dieters have had this experience. Darrin didn’t like it:

This comment from Rosedale support may be of interest to you;

“The best place to measure is under the tongue. Ideal basal temperature is what you have when you first wake up in the morning, and on the Rosedale diet should be upper 96’s lower 97’s. We have found that when someone starts our diet, their basal temperature will go down about 1-2 degrees Fahrenheit which is a great improvement”.

Personally, i did not feel good on a lower body temp when i was low carb (sub 50g) & have been working hard (following phd diet & supps) to get my body temp back up. i would say my basal/morning oral temp is now around the 97.5F on average (up from around 96.5F average pre PHD).

Low body temperatures are associated with a variety of negative health outcomes. For instance, low body temperature is immunosuppressive, leads to poor outcomes in infections, and is a significant independent predictor for death in medical patients. Fever is curative for most infections, low body temperature is a risk factor for infections. Readers of our book know that we think infections are a major factor in aging and premature death. Whether a diet so restricted in carbs that it significantly lowers body temperature is really optimal for longevity is, I think, open to question.

There is a plausible case to be made for the Rosedale diet as a diet that sacrifices certain aspects of current health in the hope of extending lifespan. It cannot however claim to be the optimal diet for everyone. It is certainly not optimized for fertility, athleticism, or immunity against infections.

Conclusion

I am sympathetic to the broad perspective that underlies Dr Rosedale’s diet. Both our diets are low-carb, low-protein, and high-fat, and studies of longevity are the biggest factor motivating the recommendation to eat a fat-rich diet.

However, Dr Rosedale takes low-carb and low-protein dieting to an extreme that I think is not well supported by the evidence.

Dr Rosedale’s direct attempt at refuting our diet consists mainly of two claims:

- Lower blood glucose is better than higher blood glucose.

- The way to lower blood glucose is by eating fewer carbs.

Neither claim is supported. Mortality is a U-shaped function of blood glucose and blood glucose levels around 90 to 100 mg/dl are healthiest, not low blood glucose levels. Moreover, the diet that delivers the lowest blood glucose levels is a high-carb, insulin-sensitizing diet, such as the Kitavans eat, not a low-carb diet.

If I truly believed Dr Rosedale’s argument for lower blood glucose, he would have persuaded me to eat a high-carb Kitavan-style diet. However, I am not persuaded.

I believe that:

- Optimal blood glucose levels are in the 90 to 100 mg/dl range. High-carb diets cause below-optimal levels of blood glucose, especially during fasts. (Indeed, high-carb dieters routinely experience hunger and irritability during long fasts.) Very low-carb diets cause elevated blood glucose due to the body’s efforts to conserve glucose by suppressing utilization. Excessive suppression of glucose utilization is unhealthy.

- A 20% carb diet, while not optimal for every single person, is healthy for nearly everyone. Twenty percent may be the best single prediction of the optimal carb intake for the population as a whole. Even diabetics can do well eating 20% carbs.

And that is why we recommend moderate consumption of safe starches.

Hi Cindy,

I haven’t had any free time to get caught up on projects, like making the presentation copyright-clean. I’ll get to that as soon as I can.

Hi Ira,

Thanks for introducing me to Bob Ranson, I hadn’t heard of him or his case.

Hi Everyone,

Paul I have a question for you as I am very curious.

I have read Gary Taubes’ Good Calories, Bad Calories book, as you reference at one stage, and I am totally sold on all the information in it.

But I’m not a little confused in conflicting opinions. The main part of Good Calories, Bad Calories I’m referring to here is that fat burning is switched off when carbs are ingested, and isn’t allowed to take place until insulin levels are low again. Insulin is also seen as the fat storage hormone. As well as that, fatty acids need glycerol-3-phospate to bind to become a triglyceride, and the body makes this from carbohydrates. So if you don’t eat many carbs theres no glycerol for them to bind to to store.

In a comment above, I notice you say that carbs and insulin do not cause obesity. Why do you think this?

Also, what you say about muscle being 76% fat, and the primary storage area that increases in size to store excess calories, are you basically saying it should be fat that is increased to build muscle rather than protein?

Thanks.

Hi,

I meant “But I’m NOW a little confused in conflicting opinions” in the post above.

Hi Leighan,

Taubes’s analysis is a little oversimplified. Insulin is more a coordinating hormone, it adjusts usage of multiple macronutrients in all sorts of tissue in order to keep blood levels in healthy ranges. There are other hormones involved with fat storage too. In general, fat cells are meant to pull in energy after meals and release it between meals, and this is good for you; inability to do that results in diabetes. Unless you are starving, which is not good, there’s generally enough glycerol for fat cells to store fats. Carb-starvation is not a good strategy for healthy weight loss.

I’m going to be offering my own theory of obesity shortly, but you can look at all the slender populations eating high carb diets for evidence that carbs and insulin do not cause obesity. Carb restriction can be helpful for weight loss, but that is not the same thing as carb consumption causing obesity. Also, I believe that low-to-moderate carb consumption is optimal for health, but that doesn’t mean that high carb consumption will result in obesity. Obesity has a lot more to do with omega-6 fats than with carbs.

Muscle needs both fat and protein – and some glucose too. To build muscle effectively, you want the nutrients to be in a good proportion, so that no nutrient is deficient and can become a bottleneck.

Best, Paul

Thanks for your reply Paul!

I must admit, the….great… thing about nutrition, is that just when you think you’ve found the answer, something else comes along and contradicts it!

I’m glad I have such an open mind in this subject. I will say, Taubes’s analysis was extremely convincing.

And I will say I do still believe that in terms of obesity, calories in vs calories out doesn’t cut it for me. Not saying exercise doesn’t play a role, because it’s brilliant for improving insulin sensitivity and so on, but I still believe it lies in what you eat.

But I did get the idea that omega-6 fats may have a bigger role in this after reading your book a few days ago.

After reading Good Calories, Bad Calories, I eliminated all carbs out of my diet. This has been for around 4 weeks now. I did notice around a week ago, 2 nights in a row I woke up with an extremely dry mouth. After reading your article with Dr Mercola I then figured that perhaps I was similar to you in the sense that zero is too low for me.

However, eating high fat and protein, I am rarely ever hungry. I usually eat my first meal at around 1pm and then dinner at 5, and then I can go all the way until 1pm or 2pm the next day before being hungry again. So I can tell I am on the right track here; this is similar to the Centenarian diets you mention towards the end of your book. I have also ordered some extra virgin organic coconut oil to use too.

I take pride in my diet being as clean and healthy as possible. I am currently 19 and started eating this way when I was 17, so I started early luckily. I want to break the super centenarian mark! However my other goal is to add muscle, and I do high intensity training, so what would your suggestions be for this? Any different?

Thanks.

Oh and I’d like to add, that I do take Dr Mercolas multi vitamin, antioxidants and pre-biotics, as far as nutrients are concerned.

thanks.

Can I remind everybody that not all starches are alike? Just like there are beneficial fatty acids, there are beneficial types of starches. Taube’s book is convincing, but completely misses the distinction that resistant starch triggers multiple metabolic changes in the body in ways that glycemic starches do not. There are now six clinical studies showing that resistant starch from high amylose corn significantly increases insulin sensitivity and effectively reduces the amount of circulating insulin. If you eliminate all carbohydrates from your diet, you’re losing resistant starch, which is found in intact whole grains (but not processed whole grains), beans, peas, bananas and high amylose corn. Numerous animal studies are demonstrating metabolic shifts from dietary consumption of high amylose corn resistant starch. The latest of these was e-published in mid-December (Zhou J, Keenan MJ, Keller J, Fernandez-Kim SO, Pistell PJ, Tulley RT, Raggio AM, Shen L, Zhang H, Martin RJ, Blackman MR. Tolerance, fermentation, and cytokine expression in healthy aged male C57BL/6J mice fed resistant starch. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research Epub 16 DEC 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201100521). This research showed that adiponectin levels in adipose fat tissue was increased following dietary consumption of high amylose corn resistant starch. This is a good thing, as adiponectin levels are lower in obese individuals. Previous research by this group at Louisiana State University has shown that the fermentation of high amylose corn resistant starch up-regulates the genes that make glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) in the large intestine, both of which are involved in satiety and insulin sensitivity. Resistant starch is a good starch and is physiologically very different than other types of starches, which are typically high glycemic. If you want to start including some carbohydrates back into your diet, make them the beneficial types of carbohydrates, not the high glycemic kind. You can find the high amylose corn resistant starch at King Arthur Flour. It’s called Hi-maize dietary fiber and is the actual ingredient used in all of these published studies.

Hi Rhonda,

I seen a protein shake that has digestive resistant maltodextrin in it rather than the usual type. Is this one of those similar carbs you mention?

Also, is organic wholegrain brown rice a good choice?

There a couple of different resistant maltodextrins that I know of in the food industry. One of the most common one is 50% fermented and 50% excreted. I haven’t seen any studies showing that resistant maltodextrin switches genetic expression and metabolism like resistant starch does. It might have similar attributes, but be less effective, simply because 50% of it is excreted.

With regards to organic WG brown rice, it will most likely be high glycemic. Rice has low quantities of dietary fiber to start with, and whether it is organic or not is mostly irrelevant to the physiological impact. If you eat it cold, it will have a low quantity of resistant starch, because the glucose chains in the rice will have cooked out of their starch granule and cooling it allows some retrogradation or crystallization, which forms resistant starch. There have been 2 studies measuring the resistant starch content of brown cooked rice. The mean amount of resistant starch was 1.7 grams of RS/100 grams of food. The highest amount tested was 3.7 grams of RS/100 grams of food. A better choice would be uncooked oats (as in granola) which have been measured to contain 11.3 grams of RS/100 grams of food. Under-ripe bananas also have between 4-5 grams of RS/banana. That starchy taste in slightly green bananas is all RS. That’s where the isolated ingredient comes in handy – it has 5.5 grams of fiber from RS in a tablespoon and can be mixed into oatmeal, a smoothie, or baked into pancakes. I can share some recipes if you’re interested.

Interesting!

So granola would be a good choice? I’ll get some if that’s the case.

Sure I’m interested in your recipes!

Do you know anything about under-ripe avocado’s? I eat a lot of those and because I’m a bad judge I often open them when they are under-ripe and eat them anyway.

Thanks.

Leighan, FYI, Rhonda is not a Perfect Health Dieter, she’s a representative for National Starch Co. which makes high amylose corn starch (http://www.nationalstarch.com/Pages/home.aspx).

Rhonda, you’re welcome to comment here, but I find some of your information a bit misleading. Potatoes are high in resistant starch, but you don’t mention them. I think it would be good if you would clarify for new visitors in the comments that your advice to eat grains is contrary to ours. Eg you could introduce your suggestions with “My advice is different from Paul’s …” so that people can more easily recognize that you don’t represent us or our diet.

Best, Paul

Paul,

I will certainly take your advice to more clearly my comments as it is not my intention to mislead. I appreciate your openness in allowing my comments on resistant starch. And yes, I work for National Starch, but I’ve read hundreds of scientific studies (out of the 367 published studies demonstrating health benefits of resistant starch), and I cannot imagine any circumstance or any diet plan that would not include resistant starch – whether from foods or from fortification – as a positive contribution.

Hi Rhonda,

It’s because you cite scientific studies that I don’t treat you as a spammer trying solely to drive up the page rank of resistantstarch.com. At the same time, I also recognize that your background is not in science, but in marketing/business development/Wharton School, and that your presentation of the science has been somewhat unbalanced.

We discuss the benefits of eating resistant starch in our book, and it is one of the reasons we recommend “safe starches” more than sugary foods. Perhaps I and others here can learn things from you; I am willing to believe that a corporate marketer can teach us valuable things about science, diet, and health. But it’s important that you present your background honestly and openly, especially in conversation with people new to our site. And if you are going to encourage others to eat corn, wheat, or oats, you need to make clear that that is your view, not ours.

Best, Paul

Yes I do have a marketing degree from The Wharton School, but I started with a Bachelors degree in Chemistry and I’ve been working in the food industry focusing on ingredients for health and wellness for more than 20 years. For instance, I’ve petitioned the FDA to take dietary fiber out of the carbohydrates category as an alternative to “net carb” labeling during the low carb days, and I have published several expert market assessments on Functional Foods in the US market. What makes it fun for me is to integrate the published scientific evidence, consumer research and needs within the boundaries of the US regulatory system to make foods better for people and to create options for better choices.

I’ve concluded after much study that the underlying insulin resistance has a tremendous impact on how people respond to carbohdyrates and starches. Within the medical community, there isn’t as much focus on measuring and improving insulin resistance as glycemic reduction, because glycemic impact is much easier to measure. But, because increasing insulin resistance directly leads to type 2 diabetes, it seems to me that anything that directly lowers insulin resistance would be beneficial. Whether it comes from corn or oats or unprocessed food is a philosophical preference. I keep coming back to the published studies – Resistant corn starch from high amylose corn actively and significantly improves insulin sensitivity and reduces insulin resistance – especially in prediabetic and overweight individuals. This is a good reason why it should be included in someone’s diet. To ask what is probably a naive question – Why should it be avoided it it comes from oats in granola or from corn – especially if the clinical studies that demonstrated the benefit used the corn-based ingredient?

Hi Rhonda,

Well, our opposition to grains is based on toxic proteins they contain. Both protein and fiber are concentrated in the bran, so the two often accompany one another.

On general principles, unless there is compelling evidence we favor whole foods rather than supplements or fortification with isolated nutrients/fiber. I don’t see the evidence for supplemental fiber as compelling, so we guide people toward “safe starches” or other fruits and vegetables rather than supplemental fiber.

I’m open to hearing evidence you have for fiber supplements, but I would need to see evidence that supplemental corn fiber is superior to natural potatoes and bananas in order to become more sympathetic. Ie, comparative evidence, not just studies that some fiber is better than no fiber. Also, I would have to be shown that the protein content is minimal.

I agree that fiber should come out of the carb category.

Best, Paul

Thanks for clarifying your opposition to grains. I’m glad that it was not the starch or carb content that you objected to.

I agree with you that the data supporting supplemental fiber is not compelling. There are a lot of differences in the physiological effects of different types of fibers. Within the research area, they are converging on three major categories – bulking (water-holding), viscous and fermenting. Each category of physiological effect delivers different health benefits. There is a tremendous amount of research on the fermentation effects within the large intestine. (i.e., the Wall Street Journal touched on some of them in “A Gut Check for Many Ailments” today) The catch is that different fibers behave differently. For instance, the LSU team uses cellulose (cell walls, bulking fiber that holds a lot of water) as its energy-equivalent control vs. Hi-maize resistant starch as the fermenting test article. Cellulose does not ferment, does not trigger the same biochemical and nutrigenomic changes that Hi-maize does, and may be great for regularity, but certainly does not trigger the metabolism shifts that Hi-maize creates.

I do find compelling the data from the Nurse’s Health Study, among others, that cereal fibers are positively correlated with reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. It’s not the fruit and vegetable fibers – it’s the cereal fiber. For instance, studies include these two – http://www.ajcn.org/content/80/2/348.full and http://www.ajcn.org/content/77/3/622.full.

There is something about the cereal fibers that is compelling for glycemic health. Maybe it’s not the cereal fiber, but it’s the cereal starch component that is making the difference. The structural barriers to digestion in cereal fibers protects the starch component during the digestive process, such that the starch reaches the large intestine, is fermented and changes hormonal responses.

I will readily admit I’m biased toward resistant starch, but I have never seen an ingredient with this strong a scientific basis supporting benefits. I’m most convinced about the improvements in insulin sensitivity, but if you want to see a broader basis of evidence on why this ingredient should be used as a supplement to the diet, send me an e-mail at rhonda.witwer@nstarch.com and I’ll share some of the summaries that we’ve compiled. I won’t send marketing information – but summaries of published studies so you can see for yourself.

FYI – The protein content of Hi-maize resistant starch is less than 1%. The fat content is also less than 1%. As the largest supplier of specialty starches to the food industry, we’re very efficient at removing protein from our starches. If it is used to supplement the diet (which was the research design in four out of the five published clinical studies), you don’t get any extra protein.

Does tapioca starch need to be cooked before consuming?

I put some into coconut milk and it tasted good.

Hi Alex,

If you don’t cook it, a lot may go as fiber to gut bacteria and you experience gas.

Alex

Cooked tapioca is so satisfying and delicious. I can’t imagine wanting to eat it uncooked.

Chebe bread is so quick…see recipe thread.

Tapioca pudding is not quick, but well worth the time. A real treat for me.

Soak 1/3 cup tapioca pearls in 2 and 1/2 cups milk overnight then cook in a double boiler for about 45 minutes till thick, add in 2 egg yolks blended with 1/3 cup rice syrup and a dash of salt and stir for a moment. Pour into serving dish and fold in 2 beaten egg whites. Eat warm or chilled.

I’m a lacto-veggie, I guess. I eat organic cheese, and sometimes regular cheese, but no eggs. I do, once in a while have a grass-fed hamburger, 93% lean, and well done. I put organic cheese on it, have gluten free wheat bread, and no HFCS ketchup. But, I do eat alot of organic cheddar cheese burritos. You say legumes are bad, but what do I replace them with besides the organic cheese pizza or burger I have instead? I have oatmeal with blackberries, coconut oil and cinnamon, with a glass of whey protein for breakfast. I have a snack of unflavored gelatin w/pineapple chunks, PNB, or crushed walnuts, and dark choc – 85& cocoa. I add some broccoli with real butter every day for lunch, and my dinner is a non GMO long grain rice cake (brown rice, and because I need something, with no corn, no soy)) with guacamole, jalapenos, and a mixture of 12 spices, including cinnamon, thyme, rosemary, oregano, flax seeds, black pepper, parsley, ginger, garlic & onion powders, cumin, and basil. And a glass of prune juice. I have been losing weight too steadily. I was 222, I’m now under 180. I want to stop, but don’t know what else to eat, or not eat. Is the organic bean and cheese burrito really bad for me? Is the organic pizza okay, as long as there is very little cheese, and I add organic mushrooms? Please e-mail me at stornor94@yahoo.com. Thank you. (I do have straight psyllium daily, and laxatives as I take heavy narcotics for pain, and they constipate me. And the daily broccoli is to ward off a second cancer bout.)

Norman, I am a nobody and not trained in nutrition. To be on this site, the obvious suggestion is to buy the book and understand the basic premises.

Since you mentioned cancer, I believe you must address the oxygenation of your blood as cancer cannot thrive in an oxgenative environment. Second, you need to consider the value of an alakaline diet. Thirdly, you need to attend to anti-oxidents for free radical conversion.

Finally, your bowel movements indicate at the least you are not consuming enough water.

Raw foods.com suggests the solution is to eat the right foods and daily enemas. I don’t know who to recommend to consult with. But, the amount of pain you have indicates you need to find a better source than you currently have. Hope this helps. Mike

OOPs. I was going to correct my misspellings.

Hi Norman,

The best thing would be to become a lacto-ovo-vegetarian and replace them with eggs. Or, even better, a lacto-ovo-pescetarian and include eggs and fish both.

You may wish to read our “Anti-Cancer Diet” post: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=4739.

Re constipation, be sure you’ve fixed any nutrient deficiencies so that you can minimize use of laxatives: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=2998.

Best, Paul

Hello Paul,

Over the passed couple months I gradually decreased my carbohydrate consumption, being inspired by this Rosedale vs. Jaminet debate. I was at the point where I went over a week having about 100 calories of carbohydrates per day from white rice, and I felt OK. Then I stopped eating the rice. At this point I was already extremely lean (user name: TangentPlane on Mercola.com – You can see my picture) and powerfully muscular. For approximately 72 hours I ate only walnuts, almonds, coconut milk (canned), beef, spinach,celery, and a lettuce mix – all USDA organic. I experienced rapid weight loss; It’s hard to say exactly how much weight since weight fluctuates a good ten pounds depending on how much water and food is in the body, but I could tell by just looking in the mirror as the flesh on my face had already begun to lessen. My mind was clearly not working at its full capacity, and I could feel a particular feeling throughout my body which I could not decide if it felt good or bad. Their are some other wishy-washy details that I could add, but here is the concrete conclusion to this experiment: First I should say that I know that I was consuming between 2300 and 3000 calories per day especially in these last 72 hours(I was weighing the food). During the last 24 hours of this 72 hours I began to feel increasingly lethargic/fatigued mentally & physically. I had some work to do and I decided to have a few blueberries. I wasn’t craving carbohydrates, I just decided to do this for one reason or another. I already had a massive amount of nuts, and coconut that day, and within 30 minutes of eating approximately 10 blueberries I began experiencing frequent moments of lightheadedness accompanied by a blurry vision phenomena where everything looks blue, green and red(a mix of colors). I believe that my body massively overreacted to the small amount of berries that I consumed. I tried to fight through this but the lightheaded feeling happened about five more times, so then I decided to eat some starches with cheese(luckily I had some raw cheese on hand). About an hour or two later, I had another similar meal. In the end of the day I probably did not exceed 500 calories of carbs…Sitting down and playing my guitar about a few hours later (10:00PM) I had feelings throughout different parts of my body that felt just like being sore. It felt similar to the after effects of a grueling day of physical activity. I wonder if the lightheaded situation would have happened if I never ate those blueberries. This all happened last night and when I woke up this morning I had a powerful craving for sugar. This type of craving did not happen when I was used to eating the starches. For now I’m going back to the starchy carbs. I have read that the heavy weight weight lifting muscle fibers use primarily carbohydrates as fuel which is probably why I have these dramatic results when restricting carbs…………

Thanks for all your work.

Regards,

Alex

Wonderful information and points. Looking forward to get rid of a few lbs .. I’ll provide some feedback once i try this. Thanks!

Since sucrose breaks down to 50% fructose does that mean that I should count half the grams of sucrose as fructose when calculating my total fructose consumption.

Hi alex – Yes.

I’ve been on the PHD for about 3 weeks. Beginning the first week I could feel the difference in terms of energy and better sleep.

Q1: After beginning the PHD, at what intervals would you recommend getting T3/rT3 checked?

Q2: How long would you expect re-balancing of hormones (thryoid, testosterone) to take? Would this be manefested as increased metabolism or thermogenesis?

Q3: Does postprandial glucose (potatoes/rice) tend to decline on PHD after the first week or so?

The book is great! Also, thanks for replying to everyone here! I find that exceptional.

Janusz

Hi Janusz,

Q1: It’s not necessary to get T3/rT3 checked unless you have hypothyroid-type symptoms and want to use these as diagnostic tools.

Q2: This is impossible to answer because different problems heal at different rates. Commonly it takes 3-6 months to eliminate nutrient deficiencies. If you are dealing with infections or other pathologies it may take years to fully recover. However, the fastest progress will typically be in the first 6 months. As you’ve experienced, some issues might improve in days.

I would say the goal is “normal” metabolism and thermogenesis. For some people that means increased, not everyone.

Q3: If you are coming from a lower-carb diet, then postprandial glucose handling will improve over a period of weeks as your body gets used to the higher carb intake.

Best, Paul

Hi Paul,

Love your book.

My mom is a t2 diabetic. She was diagnosed about 10 years ago after she almost died from diabetic ketoacidosis. She was in the ICU for over a week. She’s been on insulin 2x a day since then. She had thrush when she was in the hospital and they treated her for that. About the last five years, she’s started clearing her throat about two or three times a minute. And she coughs/chokes sometimes too. My dad said her snoring has become “violent.” She finally asked her doctor about it and they put her on an anti-histamine. It did nothing. She has dentures and last time I was there, I noticed that her denture soaking solution looked kind of dirty. Gross. I suggested to her that she change the solution every day, but she’s extra sensitive and took it as criticism. Anyway, I’m going to go to the doctor with her next time. Anything ideas of what I should suggest to the doctor to test/treat?

Hi Jenny,

Diabetics are prone to ketoacidosis and ketones promote fungal infections (actually, all eukaryotic infections — protozoa and worms as well). So it’s not surprising she got thrush when she was in the hospital for ketoacidosis. Fungal infections of the mouth will leave biofilms on dentures, and can cause rhinitis/sinusitis/epithelial infections. Elevated ketone levels might be promoting these infections.

Water helps pathogens flourish so she might try a mixed protocol with her dentures of drying them and soaking them, rather than soaking them the whole night every night.

She might want to monitor ketone levels, as well as blood glucose, as part of managing her diabetes.

Above all, she should improve her diet. A number of diabetics have reported good results on our diet, including one just last night: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?page_id=4860#comment-70547.

I don’t want to compete with doctors as far as tests and treatments, but I think she should discuss all these issues with her doctor and get the doctor’s take on how to manage ketosis as well as blood glucose, and how to sanitize dentures. Then make up her own mind. But improve her diet! That is what will help the most.

Best, Paul

Thank you very much for your reply. You are a nice man.

As a follow-up, is there a test her primary care physician can run (ie, a throat swab or blood test) to confirm a fungal infection? Also, is it common for doctors to treat fungal infections with a prescription medicine or will this need to be a diet-related fix? If it’s diet related only, I’m afraid she won’t change from her ADA approach. Thank you again.

Hi Jenny,

Yes, they can swab and culture to test for fungi.

I’m afraid dietary improvement will be the most effective course. I don’t know that the drugs would work in a diabetic on a bad diet, but she could try them. Probably even if they work temporarily, it would come back after the drugs were stopped.

Hi. Now a question about me! Just started testing my blood sugar with a home meter. PCOS, non-diabetic, overweight 30 lbs, VLC, low cortisol–especially in the am. Fasting insulin <3. My fasting blood sugar was 51 this morning! I retested and it didn't register. So, I panicked and ate a banana. 1 hr = 124, 2 hr = 92, 3 hr = 91. Could my low fasting bs be caused by my low am cortisol? Any suggestions/comments? I want to add safe starches, but I'm afraid. I think I'll add a half sweet potato or plantain with breakfast and test again.

Hi Jenny,

Clearly VLC wasn’t working for you. Still, blood sugar shouldn’t have gone so low. You must be low protein too, and ketogenic, but it’s still too low.

Definitely eat bananas, potatoes, sweet potatoes, plantains. And monitor blood glucose.

I actually eat quite a bit of protein. And fat. Just not a lot of carbs. And my blood sugar is only low in the morning. During the day I didn’t go below 90. It doesn’t make sense to me why fasting BS would be so low.

Some people don’t tolerate fasting well. I don’t know why, though I often suspect a gut dysbiosis in such cases. I think Jenny Ruhl of Blood Sugar 101 might be able to advise you.

@Jenny,

with low cortisol you do not need to wonder that your BS is low in the morning. The cortisol is necessary to keep it normal, when you are fasting.

something on low cortisol and PCOS

again, there is no clear-cut picture emerging here, other than general deteriorations in cortisol rhythm

another of the few studies into this domain states

– from http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/content/18/2/333.full

Thanks Adel!

Interesting.

Last night I decided to have a little bit of greek yogurt before I went to bed. My BS was 85 this morning!! I guess I need to have a small snack before I go to bed. Also, I hadn’t slept well the previous two nights and I took a small dose of melatonin last night and slept well. Looks like sleep made a difference too! Thanks for all your help, everyone.

Jenny

Hey Paul, I love the blog! You and your wife have both made great contributions to the Paleo world. Do you have any suggestions not on losing weight, but on gaining muscle and simultaneously losing fat? What workouts would you suggest? What macronutrient ratio would be most helpful? Do you think that including more dairy would be beneficial?

Thanks,

Real Food Eater

Hi RFE,

It’s hard to do both. To do both at once, you need some intermittency – overfeeding on workout days and fasting on rest days.

Overfeed with excess calories, and extra carb+protein. High saturated and monounsaturated fat, low polyunsaturated.

Workouts – resistance exercise to near failure, including the major movements: hip hinging (deadlift, kettlebell swings), squats, pull ups, push ups or bench press. 1-2 workout days per week.

Other days less intense work, say running, mobility exercises, yoga, tai chi, play.

Do intermittent fasting and reduced calorie consumption on rest days.

Dairy does promote muscle gain.

Thanks. On the subject of dairy, what element of milk promotes tallness? I believe that on average, pastoralists have been taller than hunter gatheres and agriculturalists. Weston A Price found a pastoralist group where the average women exceeded 6 feet tall and many men came close to 7 feet tall. Do you believe that this level of height is unnatural and therefore part of the milk is unhealthy?

In contrast, do you think that a hunter gatherer group being short on average is a sign of malnutrition? I believe that the average Kitavan male was 5 foot 4 inches and women were slightly shorter. Though they were free of heart disease, could they have been malnourished? Or is it that they were of normal height and we are of above normal height?

And my final question, is it common to see groups that are free of heart disease while being malnourished? When Ancel Keys was in Rome for a health conference, someone told him that Rome did not face problems with cardiovascular disease, but with micronutrient deficiencies. I find this interesting; a population’s rate of heart disease may not be a completely good measure for health.