In the January 1 edition of The New York Times Magazine, Tara Parker-Pope’s “The Fat Trap” looks at one of the most interesting aspects of obesity: how difficult it is to keep lost weight from coming back.

I skimmed it when it first came out, but after an email arrived this morning inviting me to sign a petition authored by Gary Taubes, I decided to read it carefully.

Ms. Parker-Pope’s article is excellent. Since it presents valuable evidence on some issues I have been planning to write about, I thought I’d use it to begin expounding my theory of obesity.

The Yo-Yo Dieting Pattern

A common experience on weight loss diets is successful weight loss – but often not to normal weight – followed by unremitting hunger that requires heroic willpower to resist, and ultimate capitulation leading to weight regain. This pattern may repeat itself in yo-yo fashion.

Parker-Pope describes a recent study from The New England Journal of Medicine:

After a year, the patients already had regained an average of 11 of the pounds they struggled so hard to lose. They also reported feeling far more hungry and preoccupied with food than before they lost the weight.

While researchers have known for decades that the body undergoes various metabolic and hormonal changes while it’s losing weight, the Australian team detected something new. A full year after significant weight loss, these men and women remained in what could be described as a biologically altered state. Their still-plump bodies were acting as if they were starving and were working overtime to regain the pounds they lost…. It was almost as if weight loss had put their bodies into a unique metabolic state, a sort of post-dieting syndrome that set them apart from people who hadn’t tried to lose weight in the first place.

The study measured hormonal levels a year after the weight loss:

One year after the initial weight loss, there were still significant differences from baseline in the mean levels of leptin (P<0.001), peptide YY (P<0.001), cholecystokinin (P=0.04), insulin (P=0.01), ghrelin (P<0.001), gastric inhibitory polypeptide (P<0.001), and pancreatic polypeptide (P=0.002), as well as hunger (P<0.001).

Note that insulin levels were still lowered, even as the participants were re-gaining weight:

Decreases in insulin levels after weight loss were evident, and the interaction between postprandial period and study week was significant (P<0.001), with significant reductions in meal-stimulated insulin release 30 and 60 minutes after eating, both from baseline to week 10 (P<0.001 for the two postprandial comparisons) and from baseline to week 62 (P<0.001 for the comparison at 30 minutes; P = 0.01 for the comparison at 60 minutes).

Gary Taubes, in his petition, complains that Ms. Parker-Pope “forgot to mention that the hormone insulin is primarily responsible for storing fat in her fat tissue”; perhaps this omission was just as well.

Resistance to Weight Gain

There is variability in the response to overfeeding. Commenting on a seminal series of experiments published in the 1990s by Canadian researchers Claude Bouchard and Angelo Tremblay, Parker-Pope writes:

That experimental binge should have translated into a weight gain of roughly 24 pounds (based on 3,500 calories to a pound). But some gained less than 10 pounds, while others gained as much as 29 pounds.

Note that eating a pound’s worth of calories typically led to something like a half-pound of weight gain; this shows that weight increases lead to energy expenditure increases. This was in a study in which the subjects were prevented from exercising. Likely the weight gain would have been generally lower if the subjects had been free to move as they wished.

Genes Influence But Don’t Decide

Genes – at least the known ones – are not determinate for obesity:

Recently the British television show “Embarrassing Fat Bodies” asked Frayling’s lab to test for fat-promoting genes, and the results showed one very overweight family had a lower-than-average risk for obesity.

Successful Weight Loss Is Possible

Some people do lose weight successfully:

The National Weight Control Registry tracks 10,000 people who have lost weight and have kept it off. “We set it up in response to comments that nobody ever succeeds at weight loss,” says Rena Wing, a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University’s Alpert Medical School, who helped create the registry with James O. Hill, director of the Center for Human Nutrition at the University of Colorado at Denver. “We had two goals: to prove there were people who did, and to try to learn from them about what they do to achieve this long-term weight loss.” Anyone who has lost 30 pounds and kept it off for at least a year is eligible to join the study, though the average member has lost 70 pounds and remained at that weight for six years.

Kudos to Drs. Wing and Hill: This is precisely the kind of data-gathering effort that is needed to help us understand weight loss.

The results, at least as reported by the Times piece, aren’t what most dieters want to hear. The people who kept weight off were those who basically continued some form of calorie restriction indefinitely:

There is no consistent pattern to how people in the registry lost weight — some did it on Weight Watchers, others with Jenny Craig, some by cutting carbs on the Atkins diet and a very small number lost weight through surgery. But their eating and exercise habits appear to reflect what researchers find in the lab: to lose weight and keep it off, a person must eat fewer calories and exercise far more than a person who maintains the same weight naturally.

If this is true, then few people have figured out how to cure their obesity. Rather, they’ve just found ways to keep weight off while remaining “metabolically damaged.” They can’t live like normal people and maintain a normal weight.

Paleo Helps

The piece then goes on to discuss the case of Janice and Adam Bridge. Mrs. Bridge peaked at 330 pounds in 2004, now weighs 195; Mr. Bridge peaked at 310 pounds and now weighs 200.

Mrs. Bridge stays at 195 pounds with a reduced-carb Paleo-style diet:

Based on metabolism data she collected from the weight-loss clinic and her own calculations, she has discovered that to keep her current weight of 195 pounds, she can eat 2,000 calories a day as long as she burns 500 calories in exercise. She avoids junk food, bread and pasta and many dairy products and tries to make sure nearly a third of her calories come from protein.

No junk food (presumably sugar), bread, pasta, or dairy is pretty Paleo. Compared to the standard American diet, it’s low in carbs and high in protein.

Persistent Alterations in the Formerly Obese

The article points to other sources of evidence for metabolic differences between the obese and the never-obese.

[O]ne woman who entered the Columbia studies [of Drs Rudolph Leibel and Michael Rosenbaum] at 230 pounds was eating about 3,000 calories to maintain that weight. Once she dropped to 190 pounds, losing 17 percent of her body weight, metabolic studies determined that she needed about 2,300 daily calories to maintain the new lower weight. That may sound like plenty, but the typical 30-year-old 190-pound woman can consume about 2,600 calories to maintain her weight — 300 more calories than the woman who dieted to get there.

Presumably 190 pounds is still obese for the “typical” 30-year-old woman. So the reduced-weight obese woman is burning fewer calories than a same-size obese woman who never reduced her weight.

So obesity followed by a malnourishing weight loss diet often creates persistent changes that hinder further weight loss, or even maintenance of the lower weight. One observation:

Muscle biopsies taken before, during and after weight loss show that once a person drops weight, their muscle fibers undergo a transformation, making them more like highly efficient “slow twitch” muscle fibers. A result is that after losing weight, your muscles burn 20 to 25 percent fewer calories during everyday activity and moderate aerobic exercise than those of a person who is naturally at the same weight.

Another observation in these patients is persistent hunger. Self-reported hunger is confirmed by observable changes in the brain:

After weight loss, when the dieter looked at food, the scans showed a bigger response in the parts of the brain associated with reward and a lower response in the areas associated with control.

In the Columbia patients, the effect is highly persistent:

How long this state lasts isn’t known, but preliminary research at Columbia suggests that for as many as six years after weight loss, the body continues to defend the old, higher weight by burning off far fewer calories than would be expected. The problem could persist indefinitely.

What Caused the Metabolic Alterations?

Are these persistent alterations to the body caused by the original obesity, or by the malnourishing diet that produced the weight loss? Dr. Leibel believes that the cause was the obesity, but that it is slow-acting – requiring an extended period of fatness:

What’s not clear from the research is whether there is a window during which we can gain weight and then lose it without creating biological backlash…. [R]esearchers don’t know how long it takes for the body to reset itself permanently to a higher weight. The good news is that it doesn’t seem to happen overnight.

“For a mouse, I know the time period is somewhere around eight months,” Leibel says. “Before that time, a fat mouse can come back to being a skinny mouse again without too much adjustment. For a human we don’t know, but I’m pretty sure it’s not measured in months, but in years.”

However, other researchers are exploring the possibility that it was the malnourishing weight loss diet that was at fault:

One question many researchers think about is whether losing weight more slowly would make it more sustainable than the fast weight loss often used in scientific studies. Leibel says the pace of weight loss is unlikely to make a difference, because the body’s warning system is based solely on how much fat a person loses, not how quickly he or she loses it. Even so, Proietto is now conducting a study using a slower weight-loss method and following dieters for three years instead of one.

My Theory of Obesity: Lean Tissue Feedback

I’m going to be spelling out my theory of obesity over coming months, but let me introduce here a few hypotheses which can account for the data reported in Ms. Parker-Pope’s article.

I believe the brain defends not only (or primarily) an amount of fat mass, but also the health of the body, as reflected by the quantity and quality of lean tissue.

So it is plausible to speak in terms of set points, but there are two set points: a “fat mass set point”, and a “lean tissue quality set point.” The second is dominant: Lean tissue is essential to life, while gains in fat mass may diminish fitness in some environments but will increase fitness in others and are rarely catastrophic. So the tissue-quality set point usually dominates the fat mass set point in its influence upon the brain and behavior.

Feedback to the brain about the quantity of fat mass comes to the brain through a hormone, leptin, that researchers can easily monitor; but feedback about the state of lean tissue comes through the nerves, which sense the state of tissues throughout the body. Lean tissue is too important for health, and can be degraded in so many different ways, that signals about its state cannot be entrusted to a fragile, low-bandwidth mechanism like a hormone. Lean tissue signaling uses the high-bandwidth communications of the nervous system. This feedback system is hard for researchers to monitor.

So the “fat mass set point” is visible to researchers, but the “lean tissue quality set point” is invisible. This is why researchers focus on the fat mass set point, while actual dieters, who know their own experiences are not explained by a simple fat mass set point theory, resist the idea.

Malnutrition will decrease tissue quality, triggering the brain to increase appetite (to get more nutrients) and diminish resource utilization (to conserve nutrients).

If the diet is deficient in the nutrients needed to build tissue, but rich in calories, then tissue-driven increases in appetite and reductions in nutrient utilization may (not necessarily, because the body has many resources for optimizing lean tissue and fat mass independently) lead to an increase in fat mass. Eventually a rise in leptin counterbalances the tissue-driven signals, but this occurs at a new equilibrium featuring higher fat mass, higher appetite, and reduced nutrient utilization compared to the pre-obese state.

Leptin signaling is responsible for the resistance to fat mass increases. The degree to which this resistance affects outcomes depends on the quality of lean tissue. The higher the quality of lean tissue, the less the brain needs to protect it and the more sensitive it is to leptin. The lower the quality of lean tissue, the more lean-tissue drives dominate and the more the brain ignores leptin signals (is “leptin resistant”).

Malnourishing “starvation” weight loss diets degrade lean tissue, and therefore they make the brain hungrier then it was before the weight loss, more eager to conserve resources that might be useful to lean tissue, and more leptin resistant.

However, weight loss diets that restrict calories, but improve the nourishment of lean tissue, should have the opposite effect. They should make the brain less hungry, less focused on conserving resources, and more leptin sensitive.

How much has to be eaten to provide adequate nourishment to lean tissue? In Perfect Health Diet: Weight Loss Version (Feb 1, 2011), I explored this question. Just to provide the necessary macronutrients to maintain lean tissue, I believe it’s necessary to consume at least 1200 calories per day. To optimize micronutrients as well, it’s probably necessary to supplement, even on a 1200 calorie diet. This is on a perfectly-designed diet. The less nourishing the diet, the more calories will be needed to eliminate tissue-driven hunger.

The Experiences of Perfect Health Dieters

A few Perfect Health Dieters have been using our diet for weight loss for a long enough period of time – 9-12 months – to test this hypothesis.

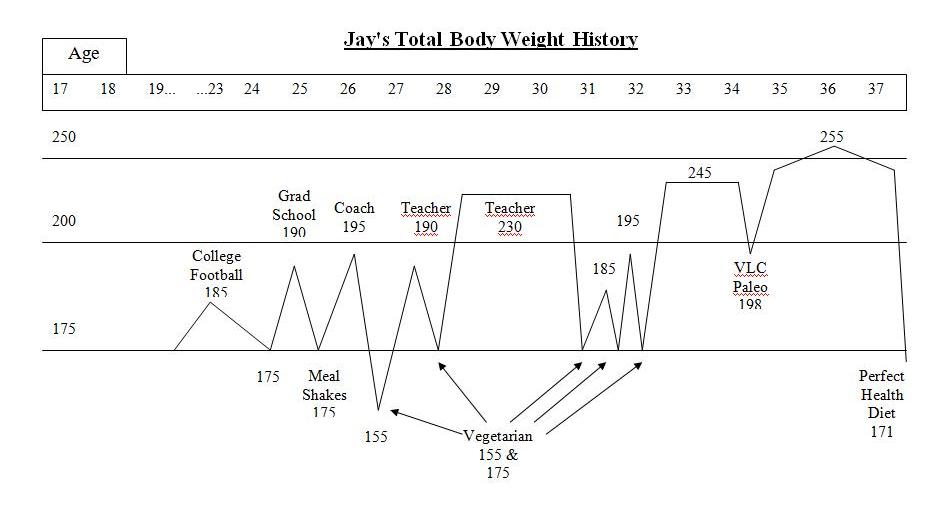

Jay Wright’s Weight Loss Journey (Dec 1, 2011) is a carefully chronicled account. Jay became overweight in college, obese by age 28, and had been obese for 10 years by the time he started our diet. He described his weight loss history:

I was a yo-yo dieter – I could lose weight but it always ended up even higher. I tried meal shake replacements, frozen dinners to limit calories, no meat/meat, no dairy/dairy, acid/alkaline, exercise/no exercise while dieting, no cash or credit cards in my wallet going to work so I wouldn’t stop at a fast food, punishment where I had to eat a raw tomato if I cheat (I hate raw tomatoes), and many other vegetarian leaning and mental tricks. A pattern emerged with these diets. I would starve with low energy for about a week or two until my will power ran out. Then, I would go eat something “bad.” If I continued to repeat the pattern and managed to be “successful,” I stayed hungry even once I reached my goal weight. I tried to transition to a “regular” amount of food to stop starving and just maintain but to no avail. My weight went right back up even higher than before even without cheating on the diets.

This yo-yo pattern of hunger followed by weight regain exactly fits the experiences described in Tara Parker-Pope’s article.

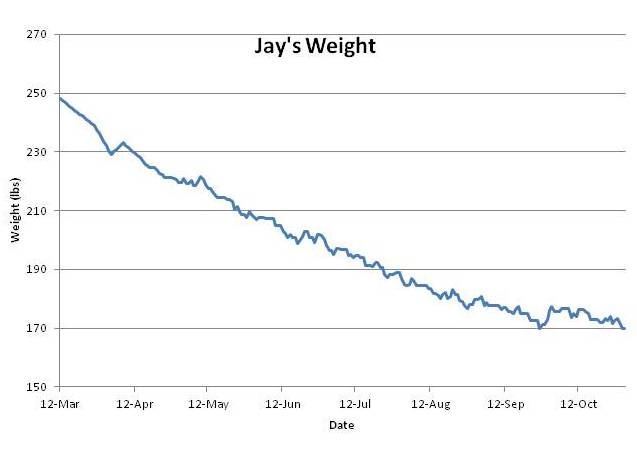

However, Jay’s experience on PHD breaks the pattern. Jay went from 250 pounds to 170 pounds – his normal weight – in six months. Weight loss was steady and he experienced little hunger. He’s maintained his normal weight without regain for 3 months.

This is just as my theory predicts. PHD is a lean-tissue supporting diet, and if his lean tissue is well nourished, he should feel little hunger. If his lean tissue heals fast enough, then his lean-tissue drive will decrease faster than his leptin signaling, his equilibrium weight determined by the balance of these two drives will always be below his actual weight, and he should experience smooth weight loss. Which he did:

Jay’s experience is counter-evidence to many of the ideas put forth by the academic researchers in Ms. Parker-Pope’s article. For instance, Dr. Leibel’s theory that months of obesity create a persistent rise in set point is refuted; Jay had been obese for 10 years but his set point was quickly reset.

Here are Jay’s before and after photos:

Conclusion

I’ll be spelling out my theory of obesity in much more detail later; this is only a first installment.

But I’ll say this: I’ve been gratified by the experiences of people who have tried our diet for weight loss. Our Results page has many reports of reduced hunger, reduced food cravings, and weight loss.

Even those who have not lost weight have reported greatly reduced hunger. I think that means their lean tissue is becoming better nourished, causing the brain to feel less urgency about acquiring more nutrients.

I think this reduction in hunger is the proper first step to healthy weight loss. And I hope that in time we can gather enough case studies to prove that a nourishing diet like the Perfect Health Diet is the best approach to weight loss — and to a genuine cure for obesity.

How interesting!! Your post reminds me of Jimmy Moore’s podcast with Greg Ellis last April.* At around 44:50 Ellis says:

—-

[After weight loss,] the fat tissue itself sends out very, very strong signals trying to make you eat. And they’re almost impossible to overcome … you start laying down body fat at a tremendous rate.

But you also want to increase your lean body mass. But the fat mass will increase up to 150% of what it was before the lean body mass gets back to where it was, and your hunger is not going to turn off until then.

—-

If true, it certainly explains why crash dieting (like the 500 cal/day for 10 weeks of the study in the NYT article) might be a great way of actually raising fat mass in the longer term rather than lowering it.

* http://www.thelivinlowcarbshow.com/shownotes/3907/dr-greg-ellis-says-bye-bye-carbs-episode-461/

Your theory makes sense, but what is the evidence that “the state of lean tissue comes” to the brain through the nerves? Jay’s experience could simply be the result of higher protein intake (curbs appetite, helps maintain lean tissue and increases metabolism), more volume from vegetables and less palatable food. Even though I like the idea that nutrition is important, I just don’t know of any evidence that the CNS receives information about the nutrient status of lean tissue through the nerves. Also there are lots of thin, malnourished people around.

Superb — I will let you know my report when I have it, as this has become my last-ditch approach by process of elimination.

I’m a veteran of many (ultimately unsuccessful) crash diets, all of which worked short-term, but I came to realize significantly depleted muscle mass (and who knows what else). I am now on a calorie-counting (1600/day) PHD, fully supplemented, but also closely monitoring strength gains using a Body By Science-style slow-motion lifting protocol. As part of that I have been trying a Leangains-style starch load (all “safe”) once a week after my lift. (a load = ~200g in the day, so nothing untoward.)

So far progress has been slow, but consistent — and though I am heavier by 10lbs still than my “low” following the last crash, I have visibly far less fat and my clothes fit as well as they did ten pounds lighter.

We’ll see in about three more months how I end up and how well it stays that way.

All of that said, I found when I did not count calories, but still ate a very clean PHD (although too low in carbs for true PHD), my weight *gain* was significant. (10lbs in a matter of 2-3 months.) So perhaps those carbs are indeed important, or the recovery takes much longer. Or the iodine increase to 12.5mg/day takes some adjusting. Or weight-training plus an unrestricted sat-fat PHD is the king of all bulking efforts. Or or or…!

Re:

“Note that insulin levels were still lowered, even as the participants were re-gaining weight:

Decreases in insulin levels after weight loss were evident, and the interaction between postprandial period and study week was significant (P<0.001), with significant reductions in meal-stimulated insulin release 30 and 60 minutes after eating, both from baseline to week 10 (P<0.001 for the two postprandial comparisons) and from baseline to week 62 (P<0.001 for the comparison at 30 minutes; P = 0.01 for the comparison at 60 minutes)."

I just looked over the study again and I was struck by the lack of a graph or any actual data for insulin unlike all the other hormones.We are told they were lower at week 10 and week 62 from baseline — but no actual numbers. And we're not told their insulin status from week 10 and 62. I don't we can dismiss insulin as a player on the basis of this study.

BTW, there are hints in the literature that the hypothalamus senses protein intake.

The Atlantic had an article (by Meghan McCardle) about Mrs Bridges and her weight history. It mentioned that Mrs Bridges is 5′ 5″ tall, so 195lbs is pretty far over what she should weigh. The article also mentioned that Mrs Bridges considers leisurely bike rides and gardening as exercise. From the article, I didn’t get the impression that Mrs Bridges is actually very aware of what constitutes proper nutrition.

Paul, I think you are spot on. I’m coming up on my one year anniversary of eating PHD style and taking all the supplements, following several previous years of low carbing. Weight management is not my issue, but I can attest to the lack of hunger on this nourishing diet. For me, low carb dieting produced cravings for wheaty carbs; the PHD diet has put thinking about food totally out of my mind. I really noticed this over the holidays. Everyone about me was clamoring for the next meal, while I was not hungry and had absolutely zero interest in the ubiquitous holiday treats on offer. Honestly, in the past few months I’ve had to consciously eat more to maintain weight. My personal experience convinces me that there is a strong relationship between nutritional status and the our brain’s drive to consume.

Two quick comments:

1) The article doesn’t mention any form of strength training. Exercise is defined as aerobics (sometimes very low impact, like walking). The only benefit considered is the additional expenditure of calories. The lean tissue quality & mass isn’t considered at all.

2) I find that on a paleo diet it is easy not to feel hunger on a mild calorie deficit diet (say 400 cal below expenditures). The point is to stay away from super-calorie-dense foods. That’s easy on a paleo diet. The difficulty lies in combining a calorie deficit with a high amount of proteins. This implies eating several chicken breasts or tuna cans a day, as no other food provide as much protein per calorie. That does get tiring fast.

JD

@Mirrorball: “Your theory makes sense, but what is the evidence that “the state of lean tissue comes” to the brain through the nerves?”

It’s a theory… Evidence not required, just plausibility. But there are plenty of paleo weight-loss stories out there to give this theory some weight. Coupled with the utter failure of other approaches…

If certain foods, or malnutrition, causes weight loss, then reversing those conditions should reverse weight loss. Mechanism is less important, although of interest to the academics, it’s not helpful to those attempting to actually accomplish a goal. 🙂

It seems clear to me that one’s body can’t have a way to measure one’s overall weight. That would require force sensors in the feet that have long term stable calibration, and that seems implausible to me. So I think there can’t be such a thing as an overall setpoint for total body weight.

It does seem possible that there could be separate setpoints for different kinds of body tissues – such as fat tissue, perhaps – but you’d have to establish that sensing mechanism(s) with long term stability were feasible. In any event, if there were a relatively stable setpoint for fatty tissues (and if all fatty tissues in the body were monitored by this mechanism), this wouldn’t explain why some people put on fat, and some have a hard time losing it. Instead, you’d have to explain why the formerly stable sensing system no longer was stable. And then you’d have to explain why it might become stable again at a higher fat level.

These things might indeed be going on, and yet still be just part of the story. Or perhaps they aren’t going on to an important degree. The idea that the body (and brain) wants to eat until there is enough nourishment for health in other tissues than fat seems to be eminently sensible and rather simpler. Let’s see what evidence Paul presents in future installments!

Paul:

Congratulations! I’m glad to see you finally putting this forth.

We know from the current scientific literature that satiety is nutritionally driven, and satiation is an estimate of future satiety.

It must be so. Any animal whose hunger drives didn’t coincide with its nutritional needs would become malnourished or poisoned — and therefore outcompeted by others, whose hunger drives did coincide with their nutritional needs.

The concept of “lean tissue quality”, of course, includes our brain and all our organs as well as our muscles…and I agree that our hunger drives must exist to satisfy the needs of our lean tissue. Nothing else makes evolutionary sense — and the current research in the field of hunger and reward supports this interpretation, including the ways in which those drives go awry in modern times.

I’m tempted to continue here, but I don’t want to spoil your party 🙂 I look forward to the rest of your presentation.

JS

I’m interested in seeing an exact list of the foods required for your 1200 calories, with maybe a fitday (or other) listing of the breakdown in micronutrients. The reason I ask is that I’ve been trying to produce the same myself and am having a lot of trouble with it, and I wasn’t going that low. I had started with Chris Kresser’s list of 14 best foods, and your recommendations and built from there, trying to avoid all toxins etc. I finally came up with the list I’ll include at the end of this, for 2000 cal.

Fitday doesn’t include everything, like K2 or even Omega 3s vs 6, and I was using the Daily Values option, which is not adjusted for gender/age etc. They also mysteriously had no micronutrients for salmon, so I entered a wild salmon with all the data. I was also trying to include foods that I liked as well, as this was designed for me.

The nutrients that I was having the most problems with getting enough of were vit E, (as the best source is seeds, which I had excluded. I ended up using olive oil to get it),calcium (with no dairy, of course), and B5. I had to include a preposterous amount of greens (IMO!) to get these nutrients to 100%. I read all of the time in paleo blogs that eating a ton of vegetables isn’t necessary, but I’m wondering how true that is? In general, I mean. Vit D, and Thiamin were also borderline.

I was aiming for an introductory, autoimmune appropriate diet, so I didn’t include eggs, or most dairy etc.

I did include some sweet fruit at first, such as berries, but found that they put the calories up too much, so I ended up dropping them.

One other thing, I started with the assumption that one didn’t need all of the nutrients every single day, so I aimed at a weekly average of intake, that’s why I have so many types of food. I figured 7 types of meat, 7 types of cooked veggies etc for each day of the week. I also didn’t want a false positive by using 1 day with oysters, for instance, when I knew I wouldn’t eat them every day.

The numbers I ended up with were

cal 2008 Fat cal 1024 Carb cal 430 Prot cal 549

I think about 300 carbs were from veggies, so that would put the carb cal count at 130, so I guess this isn’t perfectly phd.

and the following weekly grocery list

beef 1/2 kg

lamb 1/2 kg

chicken 1/2 kg

salmon 1/2 kg

shrimp 1/2 kg

oysters 1/2 kg

liver 1/4 kg

broth 7 cups

yams or other tubers 1/4 kg

onions small 14

beets 1/4 kg

asparagus 1/4 kg

artichoke hearts 3 hearts

broccolli 1/4 kg

mushroom 1/4 kg

squash winter 1/2 kg

sauerkraut or kim chee 1/2 kg

olives 7

avocado 2

coconut oil 7 tbsp

olive oil 14 tbsp

coconut milk 1 can

fish roe 70 oz

fish sauce 1/4 cup

lemons or limes 7

seaweed, dried 70 g

raw/crunchy veggies 1.5 kg

fresh veggie juice 7 cups

greens 1.2 kg

lettuce 1/2 kg

I haven’t actually bought and eaten this, as I said the amount of veggies seems like a lot, and kind of pricey, too, but if I tried to lower them, I wasn’t getting all of the nutrients. (according to fitday, that is).

So, that’s why I’m very interested in seeing a real day or week’s list for 1200 calories.

If you want the more of the fitday info, I could email you a screen shot.

But so far so good! I am waiting on tenderhooks for the rest of your theory!

Wow! I wasn’t expecting you to go there first. I suppose using the article was good segue. How might one test/experiment to detect a lean mass “setpoint”? Could it be that it is mainly neurological? I tend to lump our musculature in with our brain and CNS as the entirety of it is primarily controlled via nerve innervation (motor neurons). It may be the degradation of these nervous inputs that is somewhat catastrophic.

How are you connecting leptin and lean tissue? Are you proposing their is a feedback loop currently not under study? Also, what do you make of leptin as a cytokine and immune system/inflammatory modulator? If leptin were an inflammatory cytokine it would make sense that it would prevent hunger to prevent lipotoxicity in various tissues or alter an inflammatory response to LPS or other potentially pathogenic/harmful particulates.

Since this is the first installment i am sure much more will come of it. There is just so much to it. I’m very interested to see how you bring such a large body of research and ideas together because obesity is a manifestation of a maligned ecology which is incredibly complex.

so the big question is: what is the optimum way to induce lean tissue creation? just eating “clean” won’t do it — from my personal experience. walking (on its own) also won’t do it. strength training (body weight exercises, or weighted movement) clearly will.

my experience with PHD, is that vigorous exercise is just as necessary as dialed in nutrition. perhaps more so, as exercise can compensate — somewhat — for less than ideal nutrition, while the converse does not hold true (for me).

Perhaps the main difference between VLC Paleo and PHD is the supplements and carbohydrates. While carbohydrates are filling glycogen they are highly nourishing and desired by the body, which may explain carb cravings on VLC. Supports the malnutrition theory.

Very interesting. But can you explain exactly what is lean tissue?

Hi,

Thank you for sharing your ideas!

I’m guessing this has implications for the optimal exercise protocol. I’m under the impression that protocols similar to “lean gains” and “body by science” are optimal strategies for adding muscle mass. But then I notice you use the term “lean tissue quality” (as observed by the brain). This leads me to think that optimizing only for muscle mass might not be a good idea.

I would love to see a “perfect health exercise book” 🙂

Looking forward to the follow-up

Its the Internet, so I feel empowered to offer up my opinion like it has some basis in science. I offer my opinions as someone who has lost 80lbs following a lowish-carb/paleo/PHD type diet.

In regard to Janice and Adam Bridge (who I my mind are doing everything wrong):

1) I would suspect that their diet is heavy on the neolithic agents of disease (HT to Kurt Harris) i.e. wheat (“heart health whole grains”), vegetable oils (Linoleic acid) and fructose. I base this on the picture of the of their refrigerator:(http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2011/12/28/magazine/bridges-span-15.html) I see lots of fruit, store bought salad dressing/sauces.

2) I think that they also still live to eat. Their diet is a very “high reward” the like to eat french toast:

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2011/12/28/magazine/bridges-span-10.html

and fruit salad:

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2011/12/28/magazine/bridges-span-9.html

and I am pretty sure that they had several packages of bacon on their frig.

3) They worship at the temple of aerobic exercise. Aerobic exercise is SWPL and “is not an effective weight loss therapy” (http://alwyncosgrove.com/2011/08/aerobic-exercise-research/) The Bridges need to lift weights and do some sprinting. If we lined up Mr Bridge next to Art Devany – I would suspect that we would be shocked at Mr Bridge’s lack of muscle….

Mirrorball the brain certainly does get tremendous feedback from nerves but also one more major area Paul has not explored. The nerve that is key to this is the Vagus nerve. The other parts of the brain that sample our leanness or fatness are the circumventricular organs. The Vagus nerve innervates taste receptors on our tongue in our oropharynx esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and all the way down to the transverse mesocolon (GLP-1). Where it ends we see the high risk of colon cancers. There is an evolutionary medical reason for this……and that is where the gut bacteria take over to ferment SCFA to butyrate to protect the uncovered part of our guts.

Obesity is an inflammatory brain disorder. That has been clear for a long time. what is not clear to research scientists who think in a ruductive manner is how all the pathways interact and funnel down upon the leptin receptor.

Information in papers is not knowledge. Knowledge is gained when we understand how it all works together. Reductive thinking is how scientists get in trouble with theories.

Three thoughts:

1) The NYTIMES article is a great example of someone who’s not fluent in sciencetalking. Paul’s respone is great example of someone who is fluent. I’m not saying I agree, or that he’s right, but it is far more readable.

2) The fat setpoint vs. lean body mass setpoint could explain a lot of the gender differences in paleo style dieting. I eat a giant egg breakfast, and I’m happy until dinner. My GF just feels sick and need a lunch as well.

3) McARdle is a hypochrondriac, and an idiot to boot, but the fact that the success story is a 5′ 5″ woman weighing 195 pounds isn’t very helpful. I mean, that is fat by any measure. She easily has another 80 pounds to lose before being thin. Seems a clasic case of someone who needs to look more carefully at her food and exercise to push through a weight barrier.

the pictures at the NYTimes site tell you all you need to know about mrs bridges and her weight issues. she is clearly adverse to any physical effort or discomfort. she cons herself about “exercise” and then rewards herself with extra food. it’s no surprise her metabolism is practically quiescent, as it is clear that she has almost no muscle mass. the recumbent bike (aka lazy-boy-with-wheels) is the tell, as is the water based “exercise”.

Hi Paul! Nice! I think some lean mass set point is at play in my own weight at this point. As you may recall I eat on the higher side of the protein end b/c that keeps me happy and not hungry. If I eat low protein I’m hungry and will eat more. How to knock off the excess lean mass seems to be my problem. I feel that if I could find a way to do that, the fat may well follow.

The most important statement in this post is this: “Lean tissue signaling uses the high-bandwidth communications of the nervous system. This feedback system is hard for researchers to monitor. So the ‘fat mass set point’ is visible to researchers, but the ‘lean tissue quality set point’ is invisible.”

So, Jaminet is basing is post on an idea for which not only is there no evidence, but the evidence is nearly impossible to gather. That’s not a scientifically feasible theory. Science requires ideas that are testable.

The use of a single anecdote (Jay’s story) to exemplify the validity of Jaminet’s “theory” is also sloppy from a scientific viewpoint.

What you end up with from this post is the aphorism “Eat nourishing food to be healthy.”

Typo:

“Malnourishing “starvation” weight loss diets degrade lean tissue, and therefore they make the brain hungrier then it was before the weight loss…”

“Then” should be “than.”

After a year, the patients already had regained an average of 11 of the pounds they struggled so hard to lose. They also reported feeling far more hungry and preoccupied with food than before they lost the weight.

Totally unscientific observation: Before the lost weight, they weren’t preoccupied with food because they were immersed in it 24/7.

Paul

It will be very interesting to hear your ideas on obesity. As before I hope your thinking will encourage personal reflection and experiment My personal experience seems to point to some inconvenient “truths”. Starting with a BMI of 23.5 and now at 21.5, and caloric intake has fallen from 39.Kcal/kg to 27 (both based on the lower body weight) after an 20 month experiment. These are large and significant changes, yet without any discomfort or cravings. I am led to believe (in my case) the optimal weight and caloric intake are much lower than conventional thinking. It is also interesting why these sorts of measures are almost never raised on blogs as personal markers. Perhaps as in the physical sciences, equilibrium (body mass setpoint) is quite narrow ie “works” quite accurately in a narrow band and increasingly less so with wider deviations until the model fails to work at all. Of course this is just a model and not a mechanism that can be analysed. If that is true to some extent then the wide variation in weight loss experiences is not surprising. I have also experienced anomalous energy partition (blood glucose levels) in different body parts and very rapid responses/correlations between gut and joints which cannot be explained by hormone action and so your lean tissue idea resonates with my experience.

Umm, Jack, butyrate IS an SCFA.

@robert_evans: Hypochondriac? Sounds like Bridge is willing to do a lot more to maintain her significant weight loss than many believers in the “alternate hypothesis” are willing to do.

Beth, exactly!

Hi Mirrorball,

Evidence – it’s clear to me from personal experience that the brain does sense tissue quality. But there are no known hormones for this and I think it’s obvious that hormones could not do the job. So it must be via nerves, by process of exclusion.

Malnutrition is not a sufficient condition for obesity – only a contributing factor. I am using it here to explain the “fat trap” that makes it difficult for the obese to sustain weight loss, not to explain obesity itself. Wait for parts 2, 3, 4, etc.

Hi John,

Glad to hear you’re doing well! Less fat and more muscle is fantastic.

I think intentional calorie restriction is needed for most people to lose fat. If other issues aren’t improving fast enough, you’ll need calorie restriction to reduce the fat. If lean tissue health were good enough, then intentional calorie restriction would be unnecessary, but that can be hard to achieve.

Hi Elizabeth,

Insulin is certainly a player, but Taubes’s view is oversimplified and I thought his petition against the article deserved a mild poke.

Hi Ned,

I agree, she’s still obese, and probably doing some things wrong. But I don’t want to get personal. A lot of people are doing things wrong. At least she’s done a few things right.

Hi Kate,

Yes, that was my experience too. When I had scurvy I was ravenously hungry. As soon as I started vitamin C my appetite plummeted.

Hi Joss,

A lot of things weren’t considered in the article, but no article can consider everything.

Yes, strength training is highly beneficial. But I don’t think it’s necessary to eat huge amounts of protein, certainly not several chicken breasts or tuna cans a day.

Hi Tuck,

Thanks. It is indeed a speculative hypothesis.

Hi Tom,

I need to clarify the “setpoint” language. I am saying that a fat mass setpoint is a dynamic equilibrium, leptin is a “sensor” for fat mass but lean tissue state is also sensed, there are multiple sensing mechanisms which contribute to the equilibrium including sensing mechanisms for the health of muscle, bones, nerves, blood vessels, and organs.

I am not sure that we have evidence that the sensing mechanisms become unstable. We have evidence that the dynamic equilibrium can change. That doesn’t necessarily imply that the sensing mechanisms have changed – it’s more likely that the things being sensed have changed.

Hi JS,

Thanks much. I must go back to your work on satiation and satiety and integrate our ideas, I’m sure you’ve solved a number of issues for me.

Totally agree that “It must be so.”

Hi Trina,

Your meal plan looks great. I would add in a multivitamin and our other recommended supplements, reduce vegetables to your taste, and see how it comes out. Also, add in some safe starches like potatoes. You can displace a little meat with starches, you have 1/2 kg a day of meat which as at the top of our protein range but you’re toward the low end of our carb range. Another tweak would be butter in place of olive oil.

We’ll be working on meal plans this year, but don’t have them yet.

Best, Paul

BTW Paul, I don’t want to sound like a naysayer or stick-in-the-mud, but I think a lot of the Jay Wright anecdotes are premature. His weight history has not been stable, and three months following 1200 cal/day rather rapid weight loss diet is simply too short a time to claim victory. If you ever include such in a book, you don’t want to fall into the trap of the New Atkins where they featured success stories who had not maintained their losses. Likewise, if (I’ll be hoping for his sake that’s a WHEN) Jay maintains for a year or more, he is one person. Not a whole lot of data points on which to form a hypothesis. I hear from a lot of WAPF survivors who gained weight eating in that manner, as others did eating high fat low carb whole foods diets.

jake3_14

This is an introductory post. I’m not sure if you’re new around here, but I wouldn’t be surprised if Paul dug up some interesting and compelling data for upcoming posts in the series. Regardless, if every scientist refused to investigate things that appear to be “invisible” or unknown, what kind of progress would we have made?

Steven,

Indeed! That would certainly explain why we feel so satisfied after a well-constructed PHD meal.

Paul,

The lean tissue-nourishment connection immediately made me think of one of your presentations, in which you presented data about mice and (I believe) ad libitum feeding. While certain things varied across subject groups, the amount of protein they consumed was fairly consistent, which you proposed was a feedback mechanism. As protein is an undoubtedly essential component to healthy lean tissue, this may provide some insight as to how (and what) our body seeks proper nourishment. Looking forward to elaboration!

Paul

Of course, this is a theoretical week, but if I follow your suggestions and drop the meat, the thiamin is too low, and if I drop the olive oil, the vit E is too low, and if I drop the veggies and lot of things are too low. It’s not easy to get the DV in every nutrient! And this is at 2000 calories! That is why I am so interested to see your plans.

and Carbsane, why would you want to “knock off lean mass”? Isn’t the point to raise the lean mass and lower the fat mass?

Hi Gabe,

Interesting idea that some sort of neuropathy might contribute to obesity. As I mentioned to Tom above, I think that pathologies in the things being sensed, rather than in the sensing equipment, are most likely to contribute to obesity-related phenomena, but it stands to reason that neuropathy might be able to do it too. At least it might leave the brain under-informed and, as in the case of ghost sounds in the hearing-impaired and ghost-pain in people with lost limbs, the brain might create imaginary signals. If so, I might expect this to lead to more variance in weight in, eg, the paralyzed, compared to normal people.

The feedback between leptin and lean tissue is that both influence the brain’s regulatory system and the hypothalamus has to come to a unitary state, integrating the various signals. So if it chooses to give more influence to one signal, it has to downregulate the influence of competing signals.

Hi cjm,

Yes, exercise is highly desirable for good health. The nice thing is that a good diet increases the returns to exercise and helps motivate it.

Hi Steven,

Agreed. But as I emphasized in my interview with Dr Mercola, glucose nourishes much more than just glycogen. Half the proteins in the body need to be glycosylated for proper function, so glucose is an essential structural nutrient.

Hi Tim,

Everything except adipose tissue.

Hi Ole,

Leangains and Body by Science are excellent approaches. They’re way ahead of me as far as providing fitness guides. Maybe we’ll get to it some day – probably more along the lines of how to integrate diet & fitness, how they influence one another.

Hi Joe,

Thanks for the pictures, I hadn’t seen them. Yes, the refrigerator view suggests big improvements are still possible for the Bridges!

Ability to exercise is strongly influenced by health, so I won’t try to say what they should do, only that it certainly would be great if they could sprint and lift weights!

Hi Jack,

Thanks. Interesting that you think a reductive attitude is what prevents people from focusing on the leptin receptor.

Hi Robert,

Thanks. Interesting thought about sex differences. Will have to ponder that.

Hi Evelyn,

Having an excess of lean mass is not usually a problem – do you think your body is trying to keep a certain ratio of fat mass to lean mass?

My position is more focused on the health of bones, organs, vessels, etc., and muscles too but probably heart mass is much more influential than overall muscle mass in the feedback loop.

Hi Jake,

It’s a hypothesis … hypotheses come first, then tests. This is how science is done. I couldn’t disagree with you more.

Anecdotes are evidence, and a blog post can only hold so much for evidence. In time, we’ll gather more. But facts are like jade, hard to find and precious. One anecdote is already significant.

Jim, and erp, thanks.

Hi Morris,

Your case is a great illustration of my idea. Improving your micronutrition has decreased your calorie intake by 30%, without hunger or food cravings. This is probably due to improved lean tissue quality reducing appetite. With the reduced calorie intake, the “fat mass set point” has declined and your BMI decreased.

I think you’re right, optimal calorie intake is the lowest that perfectly nourishes us (gets every nutrient into the plateau range). That is lower than most think possible.

I’m still puzzled by your peripheral tissue experiences and gut/joint interactions, but biology has many mysteries.

Hi Evelyn,

All true and I’m aware of those issues. Still, our book has only been out one year and 7 months of impressive weight loss plus 3 months of maintenance is the best we can do.

Hi Ryan,

Great points. My presentations this fall included some of the components of the obesity theory, so you’ll see those images re-appear in coming posts.

Hi Trina,

It’s not clear how much vitamin E we need, it might be quite small, so I don’t worry too much about E. The need is reduced if omega-6 intake is low. Red palm oil is an alternative source of E, richer than olive oil.

Thiamin – a multivitamin will take care of that.

One other thing I forgot to mention is that I would try replacing some of the muscle meats with eggs, for phospholipids like choline.

Re Evelyn’s point, as I’m a work in progress, I’m very curious to see where I wind up getting (weight loss before Xmas was 130lbs). Will I plateau? Will my compulsive overeating return with a vengeance and I gain it all back? Stay tuned! For me, what has been really striking (after a lifetime of various and sundry diets) is the real lack of hunger while eating this way over last year.

I have experienced this in the past on a VLC diet which I attributed to appetite suppression via ketones. This time I wonder if it’s related to nutrient-density (thanks especially to fat-soluble micronutrients in the liver and pastured eggs I eat nearly daily). But whatever it is, it feels to me like all of a sudden my leptin sensitivity is back full force. And this despite the fact that I routinely do a “cheat” meal once a week … FTW!

Presumably it’s not that surprising that those who have lost weight (even if they are regaining) have lowered insulin compared to their obese selves, who are presumably less insulin sensitive.

Guyenet put forth some evidence of hypothalamic brain injury resulting from, I think, polyunsaturated FAs. I consider leptin an inflammatory cytokine and is why sensitivity towards it is very important. It may serve as a signal to prevent gluco/lipotoxicity. If PUFA is causing brain tissue injury in leptin sensing tissue this is very profound and may be a good reason why proper HPA functioning is suppressed by PUFA. It is interesting to me that sugar suppresses leptin release. This is probably a good thing, but is complicated by diets high in PUFA and its damaging effects on metabolism related brain sensory mechanisms.

I think some get lost regarding lean tissue feedback mechanisms due to a mental bias toward hormonal signalling. A neural mechanism would be much stronger. The idea that “phantom tissue” hunger exists is revolutionary. Does nerve transmission to motor units of lost type IIb fibers persist? This makes sense as anyone whose powerlifted and increased the expression of fast twitch fibers knows the insatiable hunger one feels as a result of it.

So, you still need to tackle many aspects and am looking forward to it.

Hi Beth,

That’s great news! We’re all works in progress, but it’s nice when the progress is positive.

Hi David,

There’s too little information to interpret it one way or another. Insulin levels are lower but as you say they may not be low. I wasn’t trying to make a positive statement so much as to remind those who focus on insulin that there is no direct correlation between insulin levels and rate of weight gain.

Hi Gabe,

Yes, “phantom tissue hunger” is a new idea we’ve come up with. If you get the Nobel prize for it, buy me dinner!

Nice article Paul.

Can you clarify what you mean by lean tissue quality? I keep getting mentally drawn into lean tissue quantity as I read your post.

“If this is true, then few people have figured out how to cure their obesity. Rather, they’ve just found ways to keep weight off while remaining “metabolically damaged.” They can’t live like normal people and maintain a normal weight.”

Whoa-this idea that we should be able to live like “normal” people is part of the problem. As you know, modern activity and diet is not congruent with our evolutionary past. Living like “normal” people these days leads to early illness and getting fat for most people. Certainly the PHD is not normal relative to what modern, first world people generally eat (which is far different than what paleo man likely ate in variable quality and quantity). People need to jettison the desire to live like normal people and find how they can live congruently with a healthy metabolism while being able to occasionally enjoy the fruits of modern life (like cheese cake!).

From the article:

“Muscle biopsies taken before, during and after weight loss show that once a person drops weight, their muscle fibers undergo a transformation, making them more like highly efficient “slow twitch” muscle fibers.”

This “slow twitch” muscle observation might be important here. Maybe the slow twitch quality is somehow connected to the body’s desire for fat tissue.

Perhaps exercise aimed at changing them to quick-switch (is that the correct term?) would help. Instead of jogging, sprinting, something like that.

Thanks for this interesting article – I’m glad I found your site.

It’s exciting to think we’re on the threshold of truly beginning to understand the role of nutrition and physical activity in health, weight level, etc.

I tend toward paleo diet thinking, but I’m beginning to see the issues are more complex – and the more physically active one is, the more carbs she or he needs.

Also, one can be “metabolically damaged” in which case modifications also have to be made.

Ron Lavine, D.C.

great post paul, can’t wait for more

I keep being reminded of CRON (Calorie Restriction with Optimal Nutrition) because it seems to dovetail with this idea of losing fat mass via calorie restriction without malnutrition. However, from what I understand of CRON, its followers are always hungry, cold, etc. even though their diets, at least in theory, are supplying them “optimal” levels of all nutrients. I suspect they probably eat little animal protein or fat, and perhaps focus on large volumes of raw food, etc. to help “fill up”, but I’m wondering what really is the difference between CRON the approach we’re discussing here.

Maybe their “optimal nutrition” is actually missing something critical?

Trina,

You might want to try Cronometer (originally created for CRON, I believe) instead of Fitday. I switched over recently and like their nutrient tracker better. It includes Omega-3 vs. Omega-6, for example.

What does this theory suggest for the skinny or underweight (who have eaten to satiety)? Would it say that for some reason the brain has determined on a low set point for lean tissue? — Perhaps early malnourishment or health problems (or simply genetics) gave them an “infrastructure” (bones and organs) that couldn’t support much lean tissue mass?

Hi Paul,

I’ll be looking forward to all your posts on this topic. I’ve been reading paleo, WAPF, low-carb sites for over a year now and following your PHD as well. You can add me to the list of your success stories as I lost 15 pounds , have no “cravings” eliminated GERD, heart palpiations, panic attacts and other annoying pains. When it comes to obesity and weight gain, i have found very interesting the observations that support the idea that low nutrient density coupled with plenty of energy (calories) plays a role in obesity. Gary Taubes was the one that first introduced this to me in his books when he mentions after famines obesity increases, when he talks about Native Americans who became obese or developed type 2 diabetes when their natural diets were eliminated and they were forced to subsist on the rations we gave them that were nutritionally empty calories, much of it wheat and sugar. Also of many “starving” countries who we feed with “grains” where some of the mothers are actually overweight. and the obese children of the great depression era, and the epigenetic studies coming out that are showing babies born to mothers whose diets consist of much of the nutritionally empty but high calorie junk food popular in today’s society or who themselves already are a victim of obesity/meatabolic dysfunction are large at birth and overweight to obese at 6 months to 2 years. (nutritional starvation in the womb?). I can look at my own family tree and note food was plentiful but devoid of much nutrition, as was my standard diet up till Jan 2011. And even those who eat a lot of fruit and veggies but limit fat are inhibiting the absorbtion of many nutrients, such as some vegans who report weight gain. Perhaps chemicals are realeased by the lean tissue in response to this lack of nutrition/ tissue degradation that are then sent to brain which then causes a drive for hunger, shuts down metabolism, etc, etc…… so much that could be going on. Of course there are the WAPF and paleo who have “gained” weight and if it could be measured my guess is that they have good nutrition but just too much “energy”..and possibly are “healthy” but overweight. just blabbing on about my own ideas here, but I think you have a great hypothesis to start with, somewhere new, with great potential ! Again I’ll be anxiously awaiting your next posts!

Shelley

Just a correction on my list of foods

fish roe should be 7 oz, not 70 oz! That’s a lot of caviar.

Hi Paul,

Love your website and your book!

I’m an RD who’s been pretty vocal about my support for carbohydrate restriction. I also received a request to sign the Taubes petition, but after reading the article and realizing I agreed with much of it, i decided against it. Your lean tissue feedback theory is very interesting. Thanks for your consistently high-quality posts.

Taubes’ petition is kind of embarrassing. I probably would have signed it without hesitation in the past.

I’ve done quite a bit of yo-yo dieting these last 10 years. Was a 20g low-carber. I never once reached goal weight but got very close before weight returned. So I will include multivitamin and minerals and more nutrient dense foods and weight training this time around (hopefully last time).

Thomas, I took “normal” to mean “able to eat reasonable calories without gaining weight”. Formerly obese folk tend to have to restrict calories to much lower than same- weight people who were never fat.

I find I maintain on 1500, gain on more. I wonder if over time, phd would alter this? Not that I’m very hungry on phd, like others, I’m feeling pretty content. And maybe 1500 is reasonable, anyway?

Paul, are you aware of the role of insulin on adipocyte proliferation? It’s the idea that insulin has an effect not only on the amount of fat in fat cells, but also on the number of fat cells. This effect can easily be seen in diabetics type 1 who’ve been injecting insulin in the same spot for years. The resulting condition is called lipodystrophy or lipohypertrophy. If injecting insulin locally has this effect locally, then secreting insulin systemically should have the same effect systemically too.

What role, if any, does the brain play in this?