This started as a note for an Around the Web, but has grown … so it will stand on its own.

The Red Meat Study

The Paleosphere has been abuzz about the red meat study from the Harvard School of Public Health. I don’t have much to say about it because the claimed effect is small and, at first glance, not enough data was presented to critique their analysis. There are plenty of confounding issues: (1) We know pork has problems that beef and lamb do not (see The Trouble With Pork, Part 3: Pathogens and earlier posts in that series), but all three meats were lumped together in a “red meat” category. (2) As Chris Masterjohn has pointed out, the data consisted of food frequency questionnaires given to health professionals, and most respondents understated their red meat consumption. Those who reported high meat consumption were “rebels” who smoked, drank, and did not exercise. (3) The analysis included multivariate adjustment for many factors, which can have large effects on assessed risk. Study authors can easily bias the results substantially in whatever direction they prefer. I’ve discussed that problem in The Case of the Killer Vitamins.

So it’s hard to judge the merits of the red meat study. However, another study from HSPH researchers came out at the same time that was outright misleading.

The White Rice and Diabetes Study

This study re-analyzed four studies from four countries – China, Japan, Australia, and the United States – to see how the incidence of diabetes diagnosis related to white rice consumption within each country.

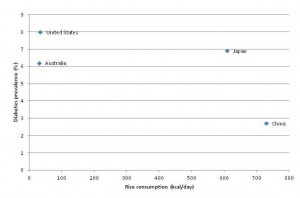

Here was the main data:

The key thing to notice is that the y-axis of this plot is NOT incidence of type 2 diabetes. It is relative risk within each country for type 2 diabetes.

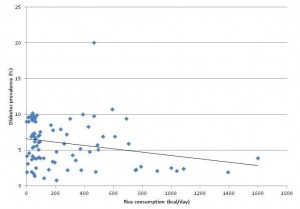

I looked up diabetes incidence and rice consumption in these four countries. Here is the scatter plot:

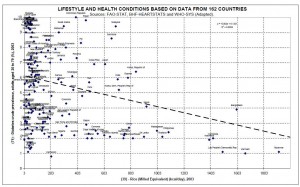

Here is the complete FAO database of 86 countries, with a linear fit to the data:

UPDATE: O Primitivo has data for 162 countries and a better chart. Here it is – click to enlarge:

If anything, diabetes incidence goes down as rice consumption increases. Countries with the highest white rice consumption, such as Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Bangladesh, have very low rates of diabetes. The outlier with 20% diabetes prevalence is the United Arab Emirates.

A plausible story is this:

- Something entirely unrelated to white rice causes metabolic syndrome. Possibly, the something which causes metabolic syndrome is dietary and is displaced from the diet by rice consumption, thus countries with higher rice consumption have lower incidence of metabolic syndrome.

- Diabetes is diagnosed as a fasting glucose that exceeds a fixed threshold of 126 mg/dl. In those with impaired glucose regulation from metabolic syndrome, higher carb intakes will tend to lead to higher levels of fasting blood glucose. (Note: this is true for carb intakes above about 40% of energy. On low-carb diets, higher carb intakes tend to lead to lower fasting blood glucose due to increased insulin sensitivity. However, nearly everyone in these countries eats more than 40% carb.) Thus, of two people with identical health, the one eating more carbs will show higher average blood glucose levels.

- Therefore, the fraction of those diagnosed as diabetic (as opposed to pre-diabetic) will increase as their carb consumption increases.

- In China and Japan, but not in the US and Australia, white rice consumption is a marker of carb consumption. So the fraction of those with metabolic syndrome diagnosed as diabetic will increase with white rice consumption in China and Japan, but will be uncorrelated with white rice consumption in the US and Australia.

Thus, diabetes incidence may be lower in China and Japan (due to lower incidence of metabolic syndrome on Asian diets), but higher among Chinese and Japanese eating the most rice (due to higher rates of diagnosis on the blood sugar criterion). This explains all of the data and is biologically sound.

What did the HSPH researchers conclude?

Higher consumption of white rice is associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes, especially in Asian (Chinese and Japanese) populations.

No: Internationally, higher consumption of white rice is associated with a significantly reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, and the Chinese and Japanese experience is consistent with that. Carb consumption is associated with a higher rate of diabetes diagnosis within populations at otherwise similar risk for diabetes. White rice consumption is correlated to carb consumption especially strongly in Asian (Chinese and Japanese) populations.

Food Reward and “Eat Less, Move More” in Diabetes

Of course, the study authors knew that diabetes incidence is lower in countries that eat more white rice. How do they reconcile this with their claim that white rice increases diabetes risk?

The recent transition in nutrition characterised by dramatically decreased physical activity levels and much improved security and variety of food has led to increased prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance in Asian countries. Although rice has been a staple food in Asian populations for thousands of years, this transition may render Asian populations more susceptible to the adverse effects of high intakes of white rice …

In other words, rice-eating countries have higher physical activity and more boring food – just look at the notoriously tasteless cuisines of Thailand, China, and Japan – and their inability to eat high quantities of food has hitherto protected Thais, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Indonesians from diabetes.

However, once those rice eaters become office workers and learn how to spice their rice with more varied flavors, the deadly nature of rice may be revealed.

Stephan Guyenet writes that “Food Reward [is] Approaching a Scientific Consensus.” It certainly seems so; it is emerging as a catch-all explanation for everything, a perspective that can be trotted out in a few concluding sentences to reconcile a hypothesis (white rice causes diabetes) with data that contradict it.

Conclusion

To me, the HSPH white rice study doesn’t look like science. It looks like gaming of the grant process – generating surprising and disturbing results that seem to warrant further study, even if the researchers themselves know the results are most likely false.

Consensus or no – and consensus in science isn’t necessarily a sign of truth (hat tip: FrankG) – the food reward perspective seems to me an incomplete explanation for what is going on. It puts a lot of weight on a transition from highly palatable (Thai, Japanese, Chinese) food to “hyperpalatable” (American, junk) food as an explanation for obesity and diabetes. It seems to me that the lack of nutrients and abundance of toxins in the junk food may be just as important as its “hyperpalatability.” It’s the inability of the junk food to satisfy that is the problem, not its palatability.

I’m glad that the food reward perspective may start being tested against Asian experiences. That may shed a lot of light on these issues.

As someone with a PhD in physics who works in the field, I imagine you know more than most about the difference between science and consensus.

“Stephan Guyenet writes that “Food Reward [is] Approaching a Scientific Consensus.” It certainly seems so; it is emerging as a catch-all explanation for everything, a perspective that can be trotted out in a few concluding sentences to reconcile a hypothesis (white rice causes diabetes) with data that contradict it.”

These are very strong words from a very level-headed blogger/author, and I couldn’t agree more.

Great post

Just remembered where the “oh my!” of the title got into my brain: Denise Minger, http://rawfoodsos.com/2010/09/02/the-china-study-wheat-and-heart-disease-oh-my/. Thanks Denise!

The white rice debate always makes me wonder: Why are Asian Americans predisposed to type 2 diabetes? I am a first generation Asian American and my father, grandmother and myself have type 2 diabetes. Compared to other folks we ate relatively large amounts of rice. Are Asian populations in general vulnerable, or only Asian Americans? Does anyone know?

Hey Paul, remember that controlled trial where they tested white rice vs. brown rice and biomarkers of metabolic syndrome? I was wondering if that was applicable. Seems to me it kind of refutes the conclusion if the study. Maybe it wasn’t extremely long duration but it’s a controlled trial.

Hi Anna,

I think the main reason is probably higher omega-6 oil consumption here, probably higher wheat and sugar consumption contribute too. Infectious disease environment is another possibility.

It could be that Asians are more vulnerable to wheat than Europeans, given the shorter history of exposure to it. Aboriginal peoples may be more sensitive to it.

Hi Stabby,

Sorry, I’ve forgotten it. Do you have a link?

http://jn.nutrition.org/content/141/9/1685.abstract

Now I suppose one could say that they’re both bad, but that’s not what these authors want to see, so their conclusion becomes absurd. I would have expected the brown rice group to do better because of the fiber content and its potential effect on metabolic syndrome, but it didn’t turn out that way. Maybe brown rice is toxic or something…

Hi Stabby,

Maybe!

I have IR (and I’m skinny as a STICK) but I’m eating small portions of white rice to keep me from losing weight. It can be done you just have to measure….

I think my IR has to do with toxic diet and low sex horomones but ill never know for sure.

Thanks Paul for your great articles and insightful analysis. White rice consumption is probably totally unrelated to diabetes. Here is my own “rice vs diabetes chart”, using more countries -> http://depositfiles.com/files/g2vxodjzf

Hi OP,

Thanks, very nice plot. I’ve added yours to the post.

We miss your blog!

The Wizard of Oz is a common source of the oh my phrasing …

Lions and Tigers and Bears, oh my!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NecK4MwOfeI

Mark

What do you think about this article on the cause of diabetes? http://paleodietnews.com/4915/paleo-diet-what-if-sugar-doesnt-cause-diabetes/

He quotes you in it.

Hi James,

Well, I basically agree, no surprise given that the bulk of it is based on a quote from this blog.

“Rice-eating countries have higher physical activity and more boring food – just look at the notoriously tasteless cuisines of Thailand, China, and Japan – and their inability to eat high quantities of food has hitherto protected Thais, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Indonesians from diabetes.”

It’s amazing how simply explicitly stating the conclusion can expose its fundamental incoherence.

Furthermore, I am in full agreement with Sean when he quotes you: “[Food reward] is emerging as a catch-all explanation for everything, a perspective that can be trotted out in a few concluding sentences to reconcile a hypothesis (white rice causes diabetes) with data that contradict it.” I, too, could not agree more.

JS

Paul,

I laughed out loud reading “tasteless cuisines of Thailand..” Thai food is the furthest thing from tasteless. Please correct me if I misunderstood you.

Hi Hristo,

Yes, we love Thai food and often cook it at home; and my wife is Chinese and the daughter of a restaurant owner and architect; so we’re familiar with the tastiness of Asian food!

Hi Paul,

Although I see it said a lot, it is a misconception that traditional Asian food was highly palatable. Highly palatable food was traditionally eaten by the wealthy, who were also often overweight. The food that most rural people ate traditionally until recently was quite plain. If you look at data from the China study for example, or if you look at the dietary habits of rural Indians, their diets tend to be very low in fat and heavily based around plain starchy staples (e.g. hand pounded or more recently white rice, millet, sorghum, sweet potatoes, or wheat chappatis). Same for traditional Africa.

When your diet consists of 60-80% rice or millet, you have access to very little fat or animal foods, and you’ve never seen a modern stove in your entire life, your diet is not going to be highly palatable. The average (rural, limited means) person was not eating complex fatty spiced dishes on a regular basis– the kinds of things we’d recognize in a restaurant– they were eating what they grew in their communities, which was overwhelmingly plain starch staples because that produced the most calories per land.

As the food in those countries has become more like what we currently think of as Thai, Chinese, Indian etc. food in the US, i.e. more diverse, more spiced/salted, less heavily reliant on plain starches, and more resembling the food of affluent nations, body fat mass and the diseases of civilization have increased.

I hear this argument a lot, “look at all the cultures that ate hyperpalatable food and were lean”, but that just does not reflect the situation on the ground if you really look into what the average person was eating traditionally. I’m not talking about what makes it into cookbooks, what the wealthy ate, or what (comparatively wealthy) Asian immigrants to the US eat; I’m talking about what the average person ate traditionally. It was simply not that palatable, just as the diets of very poor rural people throughout the world today are not that palatable.

Hello,

I side with Paul when it comes to food reward. I am Pakistani and our typical diet in the cities used to be mostly wheat chapatis or white rice eaten with meat or chicken (with gravy) twice a day, with breakfast being some form of eggs and maybe butter on toast. Seasonal fruits are typically eaten after lunch and/or dinner. We usually cook our meat with some veggies but have salads occasionally.

Those in rural areas typically eat the same food, just less meat and more of chapatis or rice and vegetables. Parathas, which is chapatis made with Ghee, is a common staple too.

Our people traditionally cooked all food in ghee which has now been replaced with vegetable/seed oils in the cities while the rural population still uses ghee. They also don’t have access to junk food or processed foods.

We’ve always used a variety of spices in our cooking and the taste of food in a particular area of the country is basically dependent on the type of spices used. The northern areas prepare less spicy but much more salty food, the southern areas prepare food so spicy that one not accustomed to it can not eat it. Traditional cuisines in our country are very palatable and Pakistani food is very famous the world over, as distinct from Indian food.

I don’t think the palatability of our food is in any way less than American junk food which I personally detest. The problem with junk is that it doesn’t satisfy hunger while providing more calories. It also doesn’t nourish like whole foods cooked traditionally do. We Pakistanis don’t eat food that doesn’t taste good and we simply can’t eat plain food without spices and seasoning. We’ve stayed pretty fit eating this way until processed foods and junk started becoming readily available. I also blame the replacement of ghee with banaspati (hydrogenated vegetable oils) and vegetable oils in general in the 80’s and 90’s for the declining health of our population.

“tasteless” Asian cuisine, XD.

i agree w/ Jarri that

“junk food doesn’t satisfy hunger while providing more calories.”

regards,

It is equally correct to say rural folks in these countries are active and also eat less calories because of availability regardless of whether it’s fatty or starchy, and therefore, have less of an insulin response than they otherwise would have (lower AUC). So, it’s not necessarily because their food is less rewarding, whatever the definition is this week.

But Stephan,

Even if the masses in those countries did eat such plain food (mostly starch, very little animal food, no spices), how do we know that it wasn’t simply the use of omega 6 oils that came at the same time as the more diverse diet that made the real difference?

“As the food in those countries has become more like what we currently think of as Thai, Chinese, Indian etc. food in the US, i.e. more diverse, more spiced/salted, less heavily reliant on plain starches, and more resembling the food of affluent nations, body fat mass and the diseases of civilization have increased.”

Hi Stephan,

I’ll meet you halfway:

– There was a cultural belief among the Chinese that the wealthy should become overweight. The symbol of wealth and success was the Buddha, http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-LCcdA3N1nJI/TmSpa22-_hI/AAAAAAAAARo/M0yRzlqsWLg/s1600/Lord-Buddha-Wallpapers-3.jpg.

– There have been many periods in Chinese history when the masses were too poor to afford more than staples. Post-Cultural Revolution 1970s communist China, the period of the China Study, was one such time – food was extremely scarce at that time due to collectivization of the farms.

But for most of its history, animal foods have been readily available in China.

Good food is tremendously important in Asian culture. Until recently food was 50% of annual expenditure and housing 10-15%; it was said in Taiwan when Shou-Ching was in college that Taiwan’s annual food expenditure could buy all its real estate. Chinese would favor spending on good food ahead of travel and other discretionary expenditures.

Spices have always been inexpensive in China and even the poorest could afford a wide range of spices including salty flavors like soy sauce or fish sauce. Also, they have many different methods of cooking which deliver a variety of flavors from the standard spices.

My wife’s personal memory extends back to 1960s Korea which was extremely poor, and her family of Chinese refugees was even poorer. Yet they ate well – animal fats and oils, fish, fresh vegetables and fruits, rice, salt and soy sauce, rich and diverse flavors.

Koreans and Japanese have simpler cooking methods than the Chinese, with an emphasis on marinades rather than oils. Yet, taking Korea as an example, they typically ate animal stews on rice with kimchi of many different flavors, and could generate very tasty stews of many flavors.

Moreover, it was traditional in China and most other Asian cultures for every extended family to gather once a week for a feast, often at a restaurant. Even the poorest did this; they could not afford restaurants, but they entertained friends and family at home and made sure to provide meat. It was an insult to fail to provide meat to guests – evidence that you didn’t value the relationship.

Your last paragraph shifts the goal posts a bit. I’m not claiming traditional food was “hyperpalatable.” I’m claiming it was palatable and satisfying – it cued the food reward system of the brain in the way evolution intended it to be stimulated, and nourished the body successfully, so that food tasted great but was also satiating and hunger-eliminating. The difference with junk food is not that it is more palatable at the time it is eaten, but that it does not satiate or nourish and therefore the brain forces the person to go seek more food. What they are seeking is nourishment, not palatability. But they have learned to seek nourishment from unnourishing foods. That is the problem.

Jarri puts it very well. Thanks Jarri!

Hi Paul,

I continue to maintain that someone who gets 70+ percent of their calories from plain starchy staples, and eats very little fat, is not going to be able to exceed a moderate palatability level in the diet. The use of spices in Asia, in my view, was to transform a very plain repetitive diet of mostly starch grains from very low palatability to low/moderate palatability.

I’m sure your wife’s family had some access to fats/oils and animal foods, but unless they were living in a community that is very different from most other traditional poor communities in agricultural regions, it would have been much less than today. Meat and (until recently with seed oils) fats are expensive foods because they require much more land to produce– this has always been an economic reality in agricultural communities. If you look at the “nutrition transition” globally as nations have modernized, it’s overwhelmingly a transition from fairly restricted, high-starch, low-fat, low animal food agricultural diets to more diverse diets higher in added fats and animal foods. There are some pockets where this doesn’t hold, but it is overwhelmingly the case globally.

Just look at Jarri’s comment above. He says that “Those in rural areas typically eat the same food, just less meat and more of chapatis or rice and vegetables.” That is an understatement. If you look at what people were eating in Punjab, a North Indian region that eats similarly to a lot of Pakistan, before industrialization they were eating mostly wheat chapatis, meat a couple of times a week if they were lucky, and only ~23% fat in the diet (mostly from dairy). I don’t know if you’ve ever had chapati, but it’s a plain flat bread traditionally made with whole wheat. This was by far the main source of calories in most peoples’ diets traditionally in N India and Pakistan. They did have ghee, in limited quantity.

Now, I’m not saying we all need to eat like the rural poor to stay lean, but it is informative to see where we came from evolutionarily speaking.

The fact that a food is nutrient-dense will not prevent people from overeating it. There is no known system in the body that adjusts appetite to micronutrient needs, besides for sodium chloride. The reason whole, natural foods are more satiating is that they tend to be less energy dense, have variable flavors (and sometimes off flavors), contain fiber and protein, often require more time and energy to chew, and don’t contain combinations of textures/flavors/macronutrients that are optimized for reward. These factors, which are nothing new to researchers who study ingestive behaviors, are more than sufficient to account for the difference in satiating value between natural and manufactured foods. There’s nothing magical about commercial junk food, it’s just been optimized to maximize reward and also happens to lack other factors that contribute to satiation and other intestinal processes that contribute to long-term body fat mass homeostasis. You can get the same effect if you manage to ‘optimize’ these variables in nutrient-dense whole foods, it’s just difficult to do without starting from a refined food palette.

Just have to chime in on the false notion that traditional diets of poor Asian population are bland. My maternal grandparents were born in early 1900s rural Taiwan. This was during Japanese rule and industrialization of the island. Everyone was poor regardless of whether one had an education or not. But the stories my grandparents and their friends told, about the lifestyle/ food they had, and also those of their own parents’and grandparents’ would dispel the myth of bland diet amongst poor people, at least for this Asian population.

Spices, sauces, flavored oils, dried/ pickled vegetables, and several types of garlic, chives, and shallots were used in cooking. Flavored, melted lard over rice was something that even the poorest of the poor could afford to eat everyday. Poor families regularly ate animal protein, mainly pork and fish, cooked in very palatable ways. They consumed them in small amounts but they did consume them.

On a side note, my grand-uncle was briefly featured in a news segment on Taiwanese tv recently, when the crew was filming a segment on one of the many natural hot springs on the island. They asked him on camera how long he’d been going to the springs, and they were shocked when he told them “over 50 years”. The crew assumed that a fit, sinewy-looking man with washboard stomach and full head of dark hair jogging up the hill to the hot spring must have only been in his 50s. He will be 86 this year. When he was asked about his youthful looks and fitness level, he told them it was due to daily hot spring soaks and walks, eating traditional diet of his childhood, and bring active in local community affairs. Sad to say he is a dying breed in industrialized Asian countries, so maybe all this talk about benefits of traditional, Asian diets will be all but nostalgic talk soon.

Hi Stephan,

I think your view is a little too narrow. I’m familiar with medieval diets, and the English (and colonial American) diets were meat rich. Grains were consumed mainly as alcohol. I would consider the medieval English diet to be somewhat repetitive, but it was over 30% meat by calories.

(I’m curious where you would place a 40% alcohol diet on the palatability spectrum.)

In general, places with lower population density and pastoral economies had meat rich diets.

Moreover, there are plenty of traditional cooking methods for creating variety and flavor. These methods probably date back to the Paleolithic, and have been used for a long time.

When people cooked at home every day, these culinary methods were probably common knowledge.

Perhaps traditional diets didn’t get into the “hyperpalatable” space that you think causes obesity, but they certainly covered a wide range in palatability without inducing obesity.

I also think you’re a little too quick to jump from short-term studies of response to food to long-term food intake. I don’t see why they should be connected.

Your last sentence is the key empirical claim that would decide between us. It would be great to test it!

Best, Paul

PS – Shou-Ching tells me that in her youth in Asia, most families raised chickens, geese, and pigs in their yards. It takes very little space to raise chickens. The family ate their own eggs every day. They caught fish and snails in the local rivers, and bought ocean fish in the markets. This was in a rural area – the village of Yeong-wol in eastern Korea (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeongwol). People in the city ate less well, but still good food was available to the middle class.

Paul and Stehan,

Please continue to discuss your very professional disagreement. This type of levelheadedness is very healthy for the rest of the community to observe, and I really enjoy seeing this conversation played out in a way that doesn’t make me feel embarrassed or annoyed.

That’s all. Just know you’re both appreciated.

Hi, Jana,

my grandma used to feed us lard + white rice (a peasant food).

sauteed shallots (or garlic or green onion) in lard, add some soy sauce.

pull it over rice.

yummy.

(we also had chicken in our yard)

FYI: we were middle class.

Stephan, we don’t need a time machine to understand this, I think, since we have contemporary Asians and their diets to observe. Here’s one observation.

Many Vietnamese have immigrated to my city, and God bless them they have opened wonderful restaurants serving authentic Vietnamese food. These places are always packed with Vietnamese and a few jealous Americans like me.

I don’t think anyone, even obesity researchers, could call this cuisine bland, simple, limited, unpalatable, unrewarding, or mostly unadorned starch. It’s incredibly tasty, full of meats, fish, offal, fats and oils, and intense flavorings such as fish sauce, lemongrass, and chile. It’s always my first choice for what to eat, and I have endless culinary choices both at home and at other restaurants of every description.

In all age brackets, these Vietnamese are, with relatively few exceptions, incredibly lean—much leaner I think than even most thin Americans like me. (They are certainly not “skinny fat,” either.) And they chow down on this delectable food with pure abandon. I often can’t eat the amounts they do, e.g., the quantity of meat in their ambrosial bone broth Pho.

My question is what definition of “food reward” or “palatability” would exclude this mouth watering cuisine? Because if you can’t exclude it, you will have to explain how this food makes people so happy and yet leaves them so lean over a lifetime.

Thanks Paul, always nice to contribute in a healthy discussion.

Regarding the point I made about rural people typically consuming less meat than those in cities, yes it is true. That’s probably one of the reasons why rural people here are generally shorter and have smaller physiques. Obesity is low, but they aren’t great physical specimens. People in cities especially in Punjab and even the poor people in the North West Frontier Province (the Pathans who are talked about so much by W.A. Price in his works) consume a significant quantity of fatty meat in their diets, always have. They are physically much stronger and are hired for manual labor for this very reason and represent one of the fittest rural people on the planet, as far as I know. Most sportsmen in our country hail from this area and have poor families, yet make it big in sports like boxing, etc. These people have always been very lean and muscular. Only in Punjab which is the richest part of the country with access to lots of processed foods has obesity and diabetes climbed in recent years. The pathans are still as fit (and poor) as ever.

Food reward doesn’t explain obesity anymore than low carb diets causing weight loss does. Just because restricting carbs causes weight loss doesn’t mean carbs cause obesity. Just because eating a bland foods based diet causes weight loss doesn’t mean that palatability of foods causes weight gain. It’s a huge leap to say otherwise.

AWESOME post.

They refuse to define what the FRH even is, so it cannot be tested, so it cannot be falsified. It is therefore, “not even wrong.”

Great link about consensus; I’m going to spread that one around. In science, all that matters is what the evidence proves, not who agrees, or how many.

Two of my recent blog posts are relevant to this discussion:

Why different people need different amounts of carbs and fat

http://www.jeffreybrauer.blogspot.com/2012/03/low-carb-or-low-fat-it-depends.html

Signaling/Nutrigenomics

http://jeffreybrauer.blogspot.com/2012/03/signaling-nutrigenomics-made-easy.html

@Stabby

Re: white vs. brown rice.

Whole grains are unhealthy; the toxins in grains are MUCH more abundant in the bran.

Paul, great post. 2 things. In regards to rice, do you think it has more to with sugar and flour–meaning is that was is missing in the analysis? I always look for those 2 things, and they always seems to lurking in the shadows. 2. Any thoughts on varieties of rice and preparation? That is, Jasmine and Basmati are pretty damned tasty and don’t seem that starchy. Also you think the vinegar use mitigates the starch effect? Just curious in regards to you thoughts and understanding on these issues.

Hari has said something very interesting, i.e., the path to ailment may not be the same as the path to health.

i have been wondering that

could there be hysteresis?

regards,

Wouldn’t Food Reward also fail to explain the “French Paradox”?

I’m enjoying this back and forth between Paul and Stephan about the causes of obesity and metabolic syndrome. I mention metabolic syndrome because I want to make clear that my comment is not solely about being overweight. I believe it is quite possible to be overweight and not suffer from the many manifestations of metabolic syndrome i.e. diabetes, high blood pressure, fatty liver, cardiovascular decease, etc. There are plenty of very sick thin people so weight should never be the sole criteria for health whether in the first world or third.

That said I’m a bit dismayed by the absence of any discussion on the role gut dysbiosis plays in the onset of the diseases that comprise metabolic syndrome. How can we discuss what foods to eat (palatable or not) and how they may contribute to disease if we fail to discuss the state of a person’s small intestine and liver? The ability to properly digest food while simultaneously keeping the body safe from the pathogens ingested with that food, as well as the pathogens that exist normally in everyone’s intestinal tract, is of paramount importance in finding a solution. There are a number of gut hormones with direct action on the brain and other digestive organs that affect hunger and satiety. Cholecystokinin, secretion, motilin, peptide YY, enterogastone, etc. are just some of the hormones produced in the brush border of a healthy small intestine. Beneficial bacteria produce B vitamins, vitamin K2, short chain fatty acids, regulate intestinal permeability, secrete antimicrobials, regulate both innate and adaptive immunity, regulate motility, gut cell growth and mucosal properties to name but a few of their essential functions. So by definition, a small intestine suffering from gut dysbiosis will produce little to none of these essential hormones, vitamins, substances, etc.

I would maintain that debating what foods are more palatable than others misses the point in the presence of a small intestine suffering the effects of alcohol or non-alcohol induced small intestinal bacteria overgrowth (SIBO), celiac sprue, gluten sensitivity, tropical sprue, candida overgrowth, parasites, etc. and the low-grade endotoxemia (sepsis) that results from increased gut permeability. A diseased small intestine such as this will not, cannot, properly send satiety signals to the brain to control hunger. Nor, for that matter, will it be capable of properly digesting the food eaten and nourishing the person eating it. It’s well known that fatty liver has an extremely high association with metabolic syndrome. In experiments with rodents, it appears that endotoxemia, i.e. the presence of gram-negative bacteria or more specifically lipopolysaccharide remnants from such bacteria and a leaky gut, is a necessary condition for this process to occur: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Changes%20in%20Gut%20Microbiota%20Control%20Metabolic%20Endotoxemia-Induced%20Inflammation%20in%20High-Fat%20Diet%E2%80%93Induced%20Obesity%20and%20Diabetes%20in%20Mice And in humans, endotoxemia appears to be key in adipose inflammation, insulin resistance and other metabolic disorders: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Experimental%20Endotoxemia%20Induces%20Adipose%20Inflammation%20and%20Insulin%20Resistance%20in%20Humans and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Is%20the%20Gut%20Microbiota%20a%20New%20Factor%20Contributing%20to%20Obesity%20and%20Its%20Metabolic%20Disorders

So if some form of endotoxemia is indeed at issue here, what changed over the last thirty years to negatively affect gut flora? Well, antibiotic overuse in both humans and non-humans over the last few generations has to be high on the list. I would maintain that poor, traditional communities had few to no opportunities of being treated with these drugs, for better or worse, than more modern communities but that is rapidly changing everywhere. Birth control pills and steroids are other drugs that would negatively affect gut flora. More powerful over-the-counter antacids that are taken by millions (to treat reflux) predisposes to small intestinal bacteria overgrowth (SIBO) as does heavy drinking. Increased intake of gluten-rich wheat and the gut inflammatory response this provokes in those genetically prone to celiac and gluten sensitivity is another route. The lower instance of metabolic syndrome in rice eating societies is probably due in no small measure to rice and not wheat being the predominant grain consumed in those still eating a traditional rice centric diet. Denise Minger’s reinterpretation of the China Study seems to suggest that this is so. Stress is another well-known route that negatively affects beneficial gut flora and with the decades-long downward mobility and economic insecurity that seems to be affecting more and more people in our country, this would be another explanation to consider. Iron overload would lead to an absolute blooming of pathogenic bacteria in a dysbiotic gut and is a well know risk factor in many disease states. This probably necessitates a reevaluation of government ordered iron supplementation of cereal grains and processed foods as well as blanket recommendations to consume iron-rich red and organ meat in the Paleo and low-carb communities without regard to the presence of gut dysbiosis. And as Paul has alluded to in the past, ketogenic diets can be downright disastrous on the mucosal layer and precipitate leaky gut. There are many ways to compromise the gut protective functions of beneficial bacteria.

The fact that bariatric surgery seems to resolve many issues in the obese apart from weight, including for some type 2 diabetes, hypertension and fatty liver, underscores the probable role of disturbed gut flora and endotoxemia in the genesis of this problem.

So while I agree with Stephan that palatability and calories are most definitely part of the puzzle, I don’t think this can completely account for the behavioral or disease states associated with obesity. There’s something more going on here and I believe that something is the state of the gut.

Hi S Andrei,

Wheat and sugar could be two of the things displaced by rice in the diet that make rice look good.

The main difference between rice varieties is probably the glycemic index and I don’t think that matters in healthy people. Check out my post on how to avoid postprandial hyperglycemia for more on vinegar and other steps to reduce glycemic response.

Hi Pam,

Yes, I do think it’s easier to prevent than to cure in most diseases.

Hi Mike,

I don’t know, food reward seems a protean theory when it comes to evaluating food.

Hi Ray,

Great points. It’s known that endotoxins in the liver cause metabolic syndrome, and that small intestinal dysbiosis often affects the pancreas and disturbs glucose regulation, but it’s not yet clear what fraction of metabolic syndrome / obesity / diabetes cases are caused by this pathway. I like your thinking, great ideas.

Best, Paul

Hi Paul,

I’m very skeptical about your statement regarding Medieval diets. Medieval Europe was not low population density except after the Plague from what I understand (when meat consumption was higher than average, according to anecdotes). Most of Europe was operating near its “Malthusian limit” judging by the periodic famines. Game hunting was strictly reserved for the royalty in much of Europe. I have a hard time believing the average person was eating a lot of meat under conditions like that.

I haven’t found any quantitative info on the colonial American diet and I have a very hard time relying on recipes, cookbooks and other anecdotes for that kind of information. What I do know is that by 1830, the average American was eating ~850 kcal/d in wheat flour alone, and not in the form of alcohol. To be fair, American health was not necessarily great overall during that time (in particular in the late 1800s), but obesity was certainly less than now. Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting it’s good for overall health to eat lots of wheat flour– I’m talking strictly about the relationship of diet to body fatness.

Regarding the short vs. long term point you brought up, “I also think you’re a little too quick to jump from short-term studies of response to food to long-term food intake. I don’t see why they should be connected.” The reason I’m so interested in food reward is precisely because it is connected to long-term body weight regulation due to the reciprocal interrelationship between energy homeostasis and reward circuits. This is something I discussed in my JCEM review paper. If you stimulate reward centers (e.g. nucleus accumbens) by electrical stimulation, you can make homeostasis centers (e.g. arcuate nucleus) light up like a christmas tree. Food reward/palatability influence satiation, satiety and long-term body fat homeostasis, so they’re ideally placed to be a major influence on body fat mass.

I’m curious to see what evidence you have to support the idea that micronutrient density influences food intake and body fat mass. In principle, I’m not opposed to the idea, and it wouldn’t surprise me if it played some role (in the general sense that everything in the body, including energy homeostasis systems, benefit from good micronutrient status), but there seems to be very little evidence to support it that I’ve encountered (besides a few observational findings and that one Chinese supplementation study that I don’t find very convincing). When the idea is brought up I never see much evidence provided to support it– it seems that people are content to assume it’s true which of course bugs me. It seems difficult to reconcile with populations around the world that have poor micronutrient status but are lean. In the US 100 years ago, nutrient deficiencies were fairly common (e.g. pellagra, goiter, rickets), and this was fixed largely by food fortification. I’m obviously skeptical but I’ll reserve judgment on this until I see what kind of evidence you have to support the idea.

“When the idea is brought up I never see much evidence provided to support it– it seems that people are content to assume it’s true which of course bugs me.”

Food reward in a nutshell. Oh the irony.

@Stephan: I don’t know if you read Paul’s last blog on food fortification, if you regard the vitamins and minerals not as “nutrients”, but as signals to your body, it may well be that this and the constant effort of the industry to increase “palpatability” act synergistically to disrupt our ability to decide when we have had enough or need more of a given “food” (don’t know if that is the appropriate word for much of what people eat these days, though).

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666386800010 , for example shows that the sensory aspect of food, which is artificially engineered in most of the things we eat regulates appetite more than caloric intake. Now, unfortunately, we have low fat foods that taste fatty these days and high carb foods that don’t taste sweet.

It is thusly no wonder that “Children showed much clearer evidence for caloric compensation than did the adults.” probably because the bodies of adults know that they cannot rely on the taste of the food in terms of estimating its caloric content, any longer

You are on the other hand right that there may be evidence for a lack of micronutrient dense foods in our diet, but even epidemiological guesswork, as I like to call it, has not been able to find the right statistical tricks to prove that this leads to increased obesity, cf.

* http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/157/8/789 [* LND = low nutrient density]

The mean amount of reported intake of several micronutrients—vitamins A, B6, and folate, and the minerals calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc—declined (P<.05) with increasing tertiles of reported number of LND foods. The LND food reporting was not a significant predictor of body mass index."

and it get’s even worseeating nutrient dense food will not only not help you stay lean, it will have you eat less and get even more obese (again according to epidemiological data, only, cf. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/content/29/suppl_1/i36.abstract)

what I find funny is that all of a sudden the “association is complex” although the message of the study clearly is that the more nutrient dense food you eat, the more likely you are to get obese… but that’s scientific bias

Can’t help but think that foods like butter, red meat, eggs, etc. wouldn’t score too highly in the NRF index which is probably based on the conventional view of what is nutrient dense, i.e. fruits, veggies, whole grains, etc.

If that is indeed the case, then the results of the study are no surprise. Eat more red meat, butter, eggs and other animal foods and stay lean!

I am of course assuming that the NRF index is bollocks.

Nutrient deficiencies may indeed be a big underlying cause of obesity but I do not think they would be a sufficient condition to induce obesity. It’s obvious economic conditions play a role; you can’t gorge on ANY food if you can’t afford it. You’ll be deficient in several micronutrients in a place like Somalia but you simply can’t eat ad libitum there and hence are not likely to become obese. Starving pretty much rules out obesity. To say that food reward is at play here would just be a fancy way of saying there isn’t enough food.

The question to be asked is, if human beings are given unlimited access to food, could they eat to their heart’s content and stay lean if the food was palatable? I believe they can, as long as the food is minimally processed. Ask the Pathans, the French, Vietnamese, Thai or any other population who stay lean despite eating palatable food and are able to afford eating palatable food everyday.

Eating only boiled, unsalted potatoes ad libitum would undoubtedly cause one to lose weight. I just don’t think it’s necessary, just as it isn’t necessary to eat a zero carb diet to avoid any insulin spike!

I think the one thing that many forget is how affordable seasonal foods, herbs, and spices are in a market economy. After seeing the differences between rural Thailand and Bangkok as a tourist and reading through the various Paleo books, the more I become convinced that one of the biggest tragedies of health is the switch from a market economy to a supermarket economy. I absolutely love having foods and flavors and recipes a available from all over the world, but we need a different way to balance technology and ancestral health, a postmodern diet that willingly embraces the past rather than demonizing it like our industrial present.

Adel:

As one might expect (and as Jarri guessed), the metric used to define “nutrient-rich foods” (NRF9.3, in the study cited) defines saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol as negative factors which decrease the NRF score.

See this easy-to-follow slide presentation about the NRF:

http://depts.washington.edu/uwcphn/news/presentations/NRF_041609.pdf

Therefore, the people defined in Streppel et.al. as eating a “nutrient-rich diet” are doing no such thing. They’re eating a low-fat diet, and they’re avoiding the most nutrient-dense foods — eggs and red meat. We would expect such a diet to be associated with greater fat mass, and that’s exactly what the data shows.

JS

In response to Anna (4th comment, above) who wrote:

“The white rice debate always makes me wonder: Why are Asian Americans predisposed to type 2 diabetes? I am a first generation Asian American and my father, grandmother and myself have type 2 diabetes. Compared to other folks we ate relatively large amounts of rice. Are Asian populations in general vulnerable, or only Asian Americans? Does anyone know?”

The study discussed in Paul’s post addressed this issue directly:

Comparing the highest white rice consumers (over 450 g/day) with the lowest consumers (under 300 g/day, roughly), the risk of diabetes was 55% higher in the heavy consumers. This applied only to the Asian populations. The more rice servings per day, the higher the risk.

The Asian populations (Japan and China) ate an average of 3 or 4 servings of white rice daily. The Western populations ate quite a bit less: 1 or 2 servings weekly.

In summary, the Harvard researchers say the risk of diabetes in the two Asian populations is related to higher white rice consumption. The overall rates of diabetes in 50 other countries doesn’t matter.

-Steve

Hi Stephan,

The Malthusian limit was different in every country. Per capita incomes were consistently twice as high in northwestern Europe than in China and Japan during the medieval period, due to two factors: less cleanliness in Europe, so that cities were mortality sinks, and lower fertility in northwestern Europe, due in part to delayed marriage (the “European marriage pattern”) and limited childbearing.

Thus, in England it took centuries for population to recover from the Black Death.

Isotope analysis of bones shows that in much of England, freshwater and marine fish was the dominant protein source. See this Michael Richards paper, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440304001025; marine fish became important in the English diet by the 9th century. England’s major export product was wool throughout the medieval era, and mutton was readily available; so was dairy.

Basically, bread, alcohol, milk/cheese, eggs, fish, mutton/lamb, and beef were the mainstays of the medieval English diet.

Colonial America had notoriously high per capita incomes compared to Europe, one reason fertility was so high. Animal foods were highly available. This changed in the early 1800s, leading into the demographic transition in the later 1800s.

Hi Steve,

From http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/#Racial:

It’s more plausible to me that Asian Americans have higher diabetes rates than Asians in Asia because the low-rice American eating pattern is worse for diabetes than the high-rice Asian eating pattern, than to blame their diabetes on rice consumption, and come up with a totally different explanation for high diabetes incidence in US whites, Hispanics, and blacks.

Hi Adel, Jarri, JS,

Great discussion. The association really is complex!

@J Stanton: You are absolutely right.

I did not intend to provide support for the hypothesis that a “nutrient rich” diet is obesogenic, but rather respond to Stephens very valid objection that we all assume that this is a “dead certain fact”, while research confirming this hypothesis is not really available… the underlying reason for the absence of pertinent scientific evidence is yet that the concept of a “nutrient dense” diet is mostly un- or maldefined

If you ever read an article on the SuppVersity, you will see that I am the last to argue that eating a well-balanced whole-foods diet (which is my interpretation of a nutrient dense) would be anything but good for your health (and what most people are unfortunately way more concerned about your weight)

On the original topic

I am also no “low-to-no-carb” fan, but if you look at the data and see that the Asians consume 400-750g of rice per day , I cannot see any reason why anybody wonders that this makes them vurnerable to diabetes