Earlier this week a paper was released to much fanfare, claiming that diets with over 20% of energy as animal protein might be as life-threatening as smoking.

- The Huffington Post said, “Atkins aficionados, Paleo enthusiasts, and Dukan devotees, you may want to reconsider what’s on your plate. While high-protein diets have been all the rage over the last few years for their waist-whittling goodness, a new study says they could be as bad for you as smoking.”

- Scientific American said “People who eat a high-protein diet during middle age are more likely to die of cancer than those who eat less protein, a new study finds.”

- NPR said, “Americans who ate a diet rich in animal protein during middle age were significantly more likely to die from cancer and other causes.” They added, “In an age when advocates of the Paleo Diet and other low-carb eating plans such as Atkins talk up the virtues of protein because of its satiating effects, expect plenty of people to be skeptical of the new findings.” A sound prognostication!

Ray, Alex, Navy87Guy, Kat, Sam, and others asked for my thoughts.

What the Researchers Did

The article appeared in Cell Metabolism, a high-impact journal which likes long complex papers reporting years of work. [1] A common strategy for getting into such journals is to piece together a great variety of work into one article, weaving a narrative theme to unite them. That’s what this article did, using the theme “high protein diets may shorten lifespan” to link several relatively disconnected projects.

The NHANES Findings

The work that generated most of the buzz was an analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). They looked at a group of 6,381 NHANES respondents and found, “Respondents aged 50–65 reporting high protein intake had a 75% increase in overall mortality and a 4-fold increase in cancer death risk during the following 18 years. These associations were either abolished or attenuated if the proteins were plant derived.”

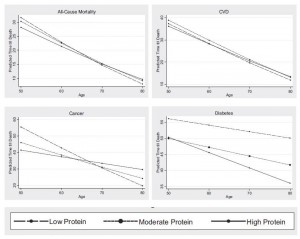

Here’s their Figure 1:

Two oddities in this result raise red flags:

- First, protein appears harmful at age 50, neutral at age 65, and beneficial at age 80. This reversal of effects is incompatible with most mechanisms by which protein could affect aging or disease risk. In animal studies, we see the opposite: protein restriction extends maximum lifespan, which means that at high ages, mortality is lower, but increases risk of early death, which means that in middle age mortality is higher.

- Second, they report that the effect was specific to animal protein: “[W]hen the percent calories from animal protein was controlled for, the association between total protein and all-cause or cancer mortality was eliminated or significantly reduced, respectively, suggesting animal proteins are responsible for a significant portion of these relationships. When we controlled for the effect of plant-based protein, there was no change in the association between protein intake and mortality, indicating that high levels of animal proteins promote mortality.” Yet, plant and animal proteins are biologically similar.

These two oddities strongly suggest that the appearance of negative health outcomes from protein is due to confounding factors – behaviors or foods associated with animal protein consumption in middle age, rather than effects caused by the protein itself.

When we look at how the analysis was performed, we find more reasons to doubt that protein is at fault. All of this data was found using a model which adjusted for the following covariates:

Model 1 (baseline model): Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, waist circumference, smoking, chronic conditions (diabetes, cancer, myocardial infarction), trying to lose weight in the last year, diet changed in the last year, reported intake representative of typical diet, and total calories.

Adjustment for a host of health-related conditions – waist circumference, diabetes, cancer, myocardian infarction, and even total calories which is effectively a proxy for obesity – can radically distort results, and even transform effects from positive to negative. I’ve discussed this issue previously in The Case of the Killer Vitamins.

In practice, many factors are highly correlated. The variables being studied – protein intake, waist circumference, total calorie intake, and others – are beset by the problem of collinearity. Attempting multiple regression analysis on collinear variables can generate very peculiar results. The more the number of adjustment factors grows, the more strange things tend to happen to data.

If they wanted us to understand whether their results are trustworthy, authors would present raw data, and then a sensitivity analysis that shows how introducing each covariate individually affects the results, then showing how including combinations of two covariates affects the results, and so forth. This would help us judge how robust the results are to alternative methods of analysis.

Of course, authors do not do this. Instead, they ask us to trust the analysis they have chosen to present – which is only one of billions they could have done. (This study adjusted for 13 covariates. The NHANES survey may have gathered data on, say, 40 variables. There are 40 choose 13, or 12 billion, possible multivariate regression analyses that could be performed using 13 covariates on this data set. Each of the 12 billion analyses would generate different outcomes.)

Are the authors trustworthy? Unfortunately, most academics today are not. Career and funding pressures are severe, and by and large those who are good at gaming the funding and publishing processes have triumphed professionally over careful, diligent truth seekers. It is much easier to construct a narrative that will garner attention and publicity and interest, than to carefully exclude non-robust results and publish only those results that are solidly supported.

Frankly, I give little credence to their NHANES analysis. And, judging by comments in the press, other epidemiologists don’t seem to give it much credence either. From the NPR article:

But could eating meat and cheese really be as bad for you as smoking, as the university news release describing the new Cell Metabolism paper suggested?

Well, that may be an exaggeration, according to Dr. Frank Hu, a researcher at the Harvard School of Public Health who studies the links between health, diet and lifestyle.

“The harmful effects of smoking on cancer and mortality are well-established to be substantial, while the harmful effects of red meat consumption are modest in comparison,” Hu wrote to us in an email.

The Mouse Experiments

So let’s turn to the next part of the study, the mouse experiments:

Eighteen-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were fed continuously for 39 days with experimental, isocaloric diets designed to provide either a high (18%) or a low (4%–7%) amount of calories derived from protein …

The low protein diets are really starvation diets, in terms of protein intake. The reason the low protein diets were sometimes 4% and sometimes 7% was because mice will often lose weight on 4% protein diets due to starvation (in the paper’s experiments on BALB/c mice, “the mice had to be switched from a 4% to a 7% kcal from protein diet within the first week in order to prevent weight loss.”). Animal control officers do not allow experiments to continue if the mice are obviously starving.

[B]oth groups were implanted subcutaneously with 20,000 syngeneic murine melanoma cells (B16).

This is an unusually small number of cells. Typically, cancer researchers implant a million cells to create a syngeneic tumor. Presumably they used this small number of cells in order to ensure that some mice would not develop tumors during the 39 day experiment. As it happened, this was a lucky (canny?) choice of cell quantity: while 10 of 10 mice on the high-protein diet developed tumors during the experiment, only 9 of 10 mice on the low-protein diet did. If they had used more cells, all mice on both diets would have developed tumors; if they had used fewer cells, some mice on the high protein diet would have failed to develop tumors. Either way, the results would appear less damning for the high protein diet.

The outcomes:

Due to the small number of cells injected, it takes at least two weeks before tumors are detectable in size (normally they would be visible in ten days). They seem to be similar in size at about two weeks after implantation.

However, when the tumors reach larger sizes, growth is impaired on the low protein diets. A mouse weighs 20 grams, and a 2000 mm3 tumor weighs 2 grams, or 10% of body weight – equivalent to a 15-pound tumor in humans. Growing a tumor of this size requires building a large amount of tissue — blood vessels, extracellular matrix, and more. The ability to construct new tissue is constrained on a protein-starved diet, so it’s not surprising that tumor growth is slower when the tumor is large and protein is severely restricted.

Animal protocols generally require that mice be sacrificed when tumors reach 2000 mm3. Extrapolating the tumor growth curves, it looks like the mice in experiment (B) would be sacrificed 5 weeks after implantation on the high protein diet, or 8 weeks after implantation on the low protein diet; in experiment (G), mice on the high protein diet would be sacrificed about 9 weeks after implantation, while mice on low protein diets would have been sacrificed about 11 weeks after implantation.

In other words, tumors still kill you, just a bit more slowly if you are starving yourself.

It’s important to note a couple of things. First, the word “starving” is appropriate. 4% to 7% protein intakes are starvation levels for mice. In a nice blog post closely relevant to this topic, Chris Masterjohn notes that a 5% protein intake completely stunts the growth of young rats:

Chris rhetorically asks: “How many of us would deliberately feed a two-year old a diet that would cause them to stop growing altogether?”

Second, as Chris also points out in the same post, such low protein intakes actually make cancer more likely in the context of exposure to mutagens. For instance, aflatoxin exposure leads to cancer (or pre-cancerous neoplasms) much more frequently in rats on low-protein diets than in rats on high-protein diets:

In this experiment, there were two diets, 5% protein and 20% protein, and two diet periods, one during exposure to aflatoxin and one afterward. Rats exposed to aflatoxin while on a 5% protein diet were far more likely to develop neoplasms than rats exposed to aflatoxin on a higher protein diet. That is, the “20-5” rats had far fewer cancers than the “5-5” rats, and the “20-20” rats had far fewer cancers than the “5-20” rats. High protein for the win!

However, once the rats had neoplasms, the tumors grew more slowly on the low-protein diet. Just as the new study found.

So, if your goal is to avoid getting cancer, it is better to eat adequate protein. If you already have cancer, or if researchers have injected you with highly metastatic melanoma cells, you can buy yourself slightly slower tumor growth by starving yourself of protein. In laboratory mice, this extends lifespan a few weeks because they are not allowed to die from cancer, but are sacrificed when tumors reach a specific size. In humans, however, cancer death commonly follows from cachexia, or wasting of lean tissue. A low protein diet might promote cachexia and accelerate cancer death in humans. It is not possible to infer from this study that there would be a clinical benefit to a low protein diet in human cancer patients.

Other Negative Effects of Low-Protein Diets

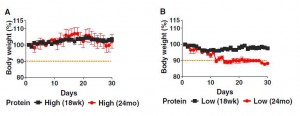

The study noted a significant negative effect of low protein diets in older mice. While young mice (18 weeks, equivalent to young adults) lost only a few percent of body weight on the starvation low protein diets, elderly mice (2 years old) wasted away on low protein diets. The data:

Both young and old mice managed to gain a bit of weight on the high protein diets, and both young and old mice lost weight on the low protein diets. The weight loss was much more severe in elderly than young mice.

Considering that wasting away commonly precedes death in the elderly, this is not a good sign for the low protein diets. The authors themselves argue that this is consistent with the NHANES finding that high protein diets become beneficial after age 65: “old but not young mice on a low protein diet lost 10% of their weight by day 15, in agreement with the effect of aging on turning the beneficial effects of protein restriction on mortality into negative effects.”

However, while I think it is clear that the dramatic weight loss in the elderly mice fed low protein is harmful, it is far from clear that the slight weight loss of the younger mice was harmless. Though they maintained their weight better than elderly mice, they may have been starving as well. To actually support the NHANES survey, the researchers should have maintained the mice on low or high protein diets for several years, and seen which group lived longer. They did not do this.

If they had, I speculate that the high protein mice would have lived longer.

Conclusion

This is a study in the line of T. Colin Campbell and other vegetarians who have tried to show that animal protein promotes cancer and mortality. These studies are unconvincing. They simply do not prove the conclusions they purport to draw.

The Perfect Health Diet takes a middle ground in regard to protein: We recommend eating about 15% protein, and argue that both high protein and low protein diets are likely to be harmful; high protein diets by accelerating aging or by making protein available to gut bacteria for fermentation, producing a less beneficial gut flora and generating nitrogenous toxins; low protein diets by starving the body of a key nutrient needed to maintain bodily functions, especially liver, kidney, and immune function.

Nothing in this study persuades me that those recommendations need revision.

References

[1] Levine ME et al. Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metabolism 19, 407–417, March 4, 2014. http://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/retrieve/pii/S155041311400062X.

Thanks for a concise but informative rebuttal, Paul! Glad we can count on you to fight “science” with science. 🙂

Paul –

Nice write up.

Q: What is the scientific evidence that supports this statement:

“high protein diets by accelerating aging or by making protein available to gut bacteria for fermentation, producing a less beneficial gut flora and generating nitrogenous toxins”

Can you elaborate please?

Thanks.

Hi Fred,

It’s discussed in Chapter 9 of our book, sources linked here: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/notes/#Ch9

Best, Paul

Thanks very much for this, Paul. You prove your indispensability time and again.

With regard to gut bacteria/protein, much of the presence of protein in the large gut can be attributed to protein that originates from the body. It isn’t necessarily dietary protein (which itself can come from both plants and animals). Furthermore, fermentation of those proteins is usually a result of lack of fermentable carbohydrate substrates in the distal colon. In other words, not enough fiber. That’s the mistake a lot of these studies make when they purport to show the deleterious effects of animal foods on the gut microbiota. It isn’t so much the presence of animal protein and fat that gives rise to unfavorable bacteria, it’s the absence of plant fiber. This is a good example:

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thesalt/2013/12/10/250007042/chowing-down-on-meat-and-dairy-alters-gut-bacteria-a-lot-and-quickly

They put people on a diet that completely lacked fiber, and then blamed meat and fat for “giving rise” to unfavorable bacteria. I’m quite sure you could achieve the same effect on a low protein, low fiber diet. It is the microbiome analog to the study you dissect here. And I suspect the same researcher motives are at play.

Paul, You are allowing me to be lazy.

I can read this stuff, pick out that it is confounding

factors, then wait a few days for you to up load the analysis.

I wish the distortion could be caught early rather than

foisting it on a public that is not equipped to understand

that bias, ideology, and fuzzy thinking are common among researchers.

I would rather believe the authors are incompetent then dishonest but

It makes me wonder if they are Machiavellian.

Dave

Nice analysis.

Paul wrote, “This is a study in the line of T. Colin Campbell and other vegetarians who have tried to show that animal protein promotes cancer and mortality.”

Certainly seems that way. As to motive, any known ties between these authors and vegetarian activists? If not, perhaps it’s just pandering to a politically-fashionable cause to keep the funding stream flowing. The ridiculous comparisons to smoking in the press statements suggest the driving factor is something other than the noble pursuit of scientific truth.

See Zoe Harcombe. Her analysis says one of the authors president of a company selling plant based protein bars.

Thank you, Paul, for once again setting the record straight. Your readers are all so grateful that you do all this hard work… so that we don’t have to! 😉

Hi Paul,

As usual, great analysis and response to the study.

I have a question: What is your opinion of Dr. Mario Pasquale’s Anabolic Diet which entails low carb M-F and high carb S-S

THE ANABOLIC DIET

Carbs %Fat %rotein % Carbs

Weekdays 30 grams 55–60 30–35 5–8

maximum

Weekends No Limit 30–40 10–15 45–60

(36–48 Hour

Carb Load)

Wouldn’t this diet average out PHD’s numbers over a week? ❓

More info: http://www.metabolicdiet.com/books/as_bb.pdf

Thanks! 😆

“First, protein appears harmful at age 50, neutral at age 65, and beneficial at age 80. This reversal of effects is incompatible with most mechanisms by which protein could affect aging or disease risk”

>> But it’s perfectly compatible with decreasing calorie intake with age, to the point where 10% protein is no more enough to thrive.

“Second, they report that the effect was specific to animal protein: … Yet, plant and animal proteins are biologically similar.”

>> Certainly, but 1/ the **FOOD** containing the protein comes with vastly different other compounds 2/ ratios of amino-acids are slightly different (think methionine)

We make our beliefs conform to the evidence of reality. We should NOT make the evidence of reality conform to our beliefs.

That is how science works.

In science, there are NO unshakeable truths at all. As a scientist we MUST challenge our views and beliefs and theories every single day. A bend over backwards type of honesty is needed. This is not present at all with Colpo et al or even MOST of the Blogosphere.

A (great) scientist will spend MUCH more time trying to DISPROVE his/her OWN ideas than he/she spends trying to show they are correct.

The easiest person in the world to fool is ourselves……

Take care,

Razwell

Nicely done, Paul.

What would be a moderate amount of protein for someone who weight trains ? Some strength coaches advocate up to 2gr per pound of bodyweight (I know insane). The more “moderate” recommendations are around 0.8 gr. per pound of bodyweight. Would that amount be considered high protein diet in the context on weight training ? Thank you !

Hi Guillaume,

I think 20% protein is pretty good if you are aiming for strength. The harder you work out, the more you will eat, so you can get a good quantity of protein without raising the percentage dramatically. That probably does work out to something close to 0.8 grams per pound of bodyweight.

Thank you very much for your reply 🙂

Hi Paul,

If I may piggy-back on Guillaume’s question… I am wondering if I ought to scale back the amount of protein recommended (.5 lbs) because I am a very small female…only 4’10”. If I read the book correctly, the carbohydrate minimum does not change…but protein and fat can be variable depending on activity and size. Should I have less than .5 protein a day…or maybe only 2 eggs instead of 3?

Thanks!

Jenny

Hi Jenny,

You can let taste be your guide. You might start by eating the yolks only, rather than the whole egg.

I have a similar question regarding protein intake per day. Unfortunately, those of us with a history of obesity and/or eating disorders can’t rely on “taste” or satiety to determine appropriate amounts. Even after many years maintaining an 80 pound weight loss, I can’t rely on satiety.

(In fact, I think this is a problem with all the diets out there, especially those that tell people to eat to satiety; this is fine for those without a serious weight problem; most people with a weight problem need fairly strict guidance, I feel.)

So, I’m not sure how much protein I need. 8 ounces or 16 ounces? Clearly it’s individual, but I don’t know how to determine my own proper amount.

we are very fortunate to be kept updated on this ever changing and challenging health journey we are on by a brilliant and analytical man,thanks for all your time and effort Paul

Concise and insightful as always, Paul!

To those who wonder if these researchers have some kind of tie to vegetarian groups, I don’t think that’s necessary. They’re arguing for a position that has mainstream popularity.

Well, such researchers may not have ties to PETA, but they may have other competing interests; Zoe Harcombe notes this about this study:

“Call me suspicious, but I always check for conflicts of interest and the lead researcher, Dr Longo, has declared interests in (actually, he’s the founder of) L-Nutra – a company that makes ProLon™ – an entirely plant based meal replacement product.”

Her analysis of the study — which is quite as skeptical as Paul’s — can be found here:

http://www.zoeharcombe.com/2014/03/animal-protein-as-bad-as-smoking/

“In practice, many factors are highly correlated. The variables being studied – protein intake, waist circumference, total calorie intake, and others – are beset by the problem of collinearity. Attempting multiple regression analysis on collinear variables can generate very peculiar results. The more the number of adjustment factors grows, the more strange things tend to happen to data.”

Robustness checking is becoming a requirement for publishing in some fields like economics. Sadly, it doesn’t appear to be a requirement in nutrition studies yet. This allows the researchers to go “specification mining” to get results that will publish. This is why I can’t take seriously 90% of observational nutrition studies.

Being published does NOT mean ANYTHING, in science. It simply does not matter.

Being published in peer reviewed literature does not mean anything either. Most people ( usually laymen) do not realize this and understand it.

I noticed that you didn’t mention anything about the approval process for this particular paper. A journal requiring the kind of collaborating research should have a correspondingly detailed process for vetting those papers.

Did the reviewers have access to the raw data to see if the statistical analyses were justified? Did they rubber-stamp the initial conclusions of the authors, or were there several rounds of reviews and re-edits? Is the review process transparent, or are those conversations kept confidential? Ever since Professor Geoffrey B West’s paper “The importance of quantitative systemic thinking in medicine” (2012), I’ve pondered how scientific research itself should change to understand those whole-system dynamics. It seems as if the review process for papers should be entirely transparent…

“Scientific American said ‘People who eat a high-protein diet during middle age are more likely to die of cancer than those who eat less protein, a new study finds.’ ”

That article did not come from Scientific American per se. It came from a content-providing company livescience.com: http://www.livescience.com/43839-too-much-protein-help-cancers-grow.html . I don’t know what sort of vetting process LiveScience has for their science-reporting articles. I also don’t understand the content-providing arrangement between Scientific American and livescience.com.

I first noticed Scientific American online content from LiveScience in a recent article “Most People Shouldn’t Eat Gluten-Free” http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/most-people-shouldnt-eat-gluten-free/ . Like many papers about gluten, that article focused on Celiac disease and ignored the large body of papers studying the impact of that protein on our brain. It also promoted the notion that one would be “stripped of nutrients” by avoiding grain — nutrients that couldn’t be easily acquired with other foods. I was deeply troubled that Scientific American would lend their credibility to articles like this.

I said, “nutrients that couldn’t be easily acquired with other foods”.

I meant to say, “nutrients that can easily be acquired through other foods.”

Paul,

Both Denise Minger and Mark Sisson have now blogged about glycine being able to reduce mortality even holding protein consumption constant. What are your thoughts about glycine supplementation?

I know it is best to get it from bone broth soup and organs but availability around my area is limited. Any cautions against glycine supplementation?

Hi Steve,

There is nothing in the literature about it; Denise has linked to a meeting abstract from 2011 but it never got published. I should write to the authors to see what the story is, but often that indicates issues with reproducibility/plausibility of the data.

I think glycine supplementation is pretty safe.

I think he loses me on the “trustworthy” comment. Motive doesn’t need to be imputed at all, to do the work he does here.

He just assumes bad motives in the absence of evidence, making it the weakest part of his argument, and partially undoing the example he creates–basing conclusions on careful evaluation of evidence.

Unfortunately, irreproducible results are rampant in biomedical papers, and fraud is also fairly common. I have the misfortune to be aware of a number of cases. In this case, however, the “trustworthiness” issue just deals with robustness of the analytical results, and in fact that’s easy to answer — they are not trustworthy. If only robust results could be published, no epidemiological studies would ever see the light of day.

There is LOTS of crap that is “published in the peer reviewed literature.” It means NOTHING. Did you know the intelligent design ( idiots) got “published in peer review literature.” ?

Stuff that is outright very wrong often gets by referees.

WHAT MATTERS is that IF it is interesting and somebody ELSE takes it up …..and THEY do EXPERIMENTS , TESTING it and it gets done more and more ….. AND the idea WORKS…THEN, and only THEN does it begin to become part of the cannon of science.

People such as Anthony Colpo, Richard Nikoley, Denise Minger, – and most of the Blogosphere – do NOT understand this CRUCIAL point !

Paul,

Have you seen this study that validates your theory about extra-cellular pathogens internalizing in cells to defend themselves from antibiotics, etc.?

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2640020/

I think your advice about IF is timely and important.

Since strep infections often occur in children, what are your thoughts on IF for them? Does autophagy start sooner (i.e. with less fasting hours per day) in them than in adults? My children and their friends are having a problem where antibiotic treatment is only partially successful in eliminating all symptoms of strep throat, and we are not really interested in going back to the dr. for more of the same (ineffective) treatment.

We are not the only ones: http://www.confessionsofadrmom.com/2011/03/strep-throat-dilemma/

Thanks!

Hi Annie,

I think fasting is a good strategy during certain infections – usually, the ones that suppress appetite. While sick, fasting can be more extensive than our usual 16-hour overnight fast with normal caloric intake. (That is, longer in duration, and caloric intake can be reduced.)

Thanks for letting me know of that paper.

Best, Paul

A note to Paul and readers seeking advice on adjusting nutrient intake relative to exercise regimens. Physical demand changes the picture of everything recommended in the PHD realm – and Paul is in the beginning stages – in the sense he doesn’t know how to make adjustments to intensity and duration. Pure strength training places much less stress on the body compared to body building and competitive endurance training – or any other high stress condition that increases protein turnover/breakdown, e.g. illness, burn victims, back to back athletic competition, etc. For comparison, any ‘out of shape’ person beginning an exercise program places more stress on their body than a seasoned, mechanically efficient power lifter. And today’s trainers too often wail on people, notwithstanding people do the same on their own. Pure strength training – mind you – demands NOT going to failure, and simply maximizing neural recruitment – not much stress if you are savvy to these concepts. However, most people over train – using a reps/exhaustion scheme – and the majority of coaches, trainers, and fitness enthusiasts do exactly just that. Protein intake varies to stress/turnover – and should be plastic, similar to glycogen/carb depletion – but varies less. Duh, training over lactate threshold utilizes 19x more glucose to produce the same power (38ATP’s) than when glucose is utilized below lactate threshold, i.e. if glucose is oxidized. The math is simply physical. 1 glucose utilized aerobically produces 38 ATP’s – no lactate produced. I’m amazed at the number of people looking for help adjusting nutrient intake related to stress and exercise intensity – and the lack of precision or fundamental knowledge on the subject in the PHD world. Your research is excellent Paul – but as if often the case – you and other authors conceive out of a static condition – and struggle to give sound advice when it comes adjusting nutrient intake for physical demands which vary to intensity and duration – or any specific activity. “Let taste be you guide” reflects this problem.

Those are good thoughts Ed but wouldn’t most of what you say apply to athletes? I am sure athletes need to follow a fairly stringent routine and probably have a diet coach to help optimize. But for the majority of people out there who work 9-5 jobs and don’t do high level athletics, it seems to me “dynamically adjusting” macro nutrients can be burdensome and even neurotic. I think there is virtue to simplicity and I doubt I would stick to a diet that requires constant optimization unless the payoff clearly outweigh the costs. Having read Paul’s book, it strikes me that he is mostly talking to avg people not high level athletes, who probably should go beyond PHD. But they are the exception not the rule.

Au contraire Steve.Ironically, the most simple thing for the average person to realize is the body stores a finite amount of glycogen the same way a gas tanks stores gasoline. I use liquid filled figurines to teach this to 5-year olds. There’s nothing neurotic about adjusting carbs relative to glycogen depletion at all. I’d say it is more simple than making a yin-yang apple shaped chart that fails to get the point across. Like a sponge – relatively intense exercise ‘squeezes’ out or depletes glycogen and little or no exercise depletes very little. This is the most simple and clear cut way to understand a relationship without confusing people. Jaminet himself upped total carb intake in his book from 20-30 to what?… up to 40% or a bit more. I guess he had a handle on ‘perfection’ and optimization? (rhetorical and sarcastic) Understanding a big picture relationship – before breaking it down into fructose and glucose percentages – is getting one simple relationship in place. It just seems more impressive. Ironically, Jaminet uses glycogen repletion – studies mostly done on athletes to get a simple idea across. The notion, ‘glycogen depletion/repletion’ only applies to athletes is short sighted. Teaching details first to people – without teaching them big picture fundamental leads to more worry and a neurotic frame of mind comparatively. Why try to put artwork up on walls, when the walls don’t exist? You got the exception and the rule reversed. As an exercise physiologist – who teaches this stuff – I assure you, details are harder to understand before the big picture is understood. You state Jaminetss diet sticks to ‘constant optimization’. That’s a joke – built on the assumption of a static condition. Even a child can view images of people sitting, biking, sprinting, and see the amount of carbohydrate is relative to how the body is used. Trying to optimize by adjusting small details (Jamimnet) is much more difficult – and takes exceptional focus. But it does ‘work’ for people.

Ed, you mention getting the “big picture” about nutrition. I searched on physicalrules.com; google couldn’t find a single occurrence of the words “ketogenic” or “ketone”. I’m not sure how it’s possible to get the “big picture” about nutrition if one doesn’t even mention this secondary energy source.

When you teach five-year-olds, do you tell them that our cells can get energy from glucose or ketone bodies? Do you tell them that that carb depletion curves happens at a far slower rate with ketogenically adapted people? Do you let them know that ultramarathoners like Timothy Olson are breaking records in races while consuming a maximum of 100 calories of carbs/hour? Or do you categorically ignore this second source of fuel for our cells?

With no due respect, (due to your impudence) apparently you think an audience of 5 year-olds need to go beyond learning the relationship between carbs in food (in general) and carb depletion relative to basic activities. Ask a high school student if they think learning about ketones for fuel is or is not a big picture idea when learning the first lessons on fuel substrate utilization. You’re being an insolent jack@$$. You’re acting out Jimmy – If you were in my class I’d tell you “go sit in the corner.” Seriously,a liquid-filled figurine teaches a relationship many adults do not understand – and even children may grasp the concept. You’re just trying to challenge me on knowledge of ketone bodies – duh. I’m an exercise physiologist, whup-dee-ding for me… but yeah I’m aware of what you are talking about, as well as your ill will. Where did you get the idea that I categorically denied ketones as a secondary fuel source? Oh yeah, you just made that up as a challenge. Former running/high carb ‘gurus’ like Timothy Noakes (Lore of Running) have found out the same thing you’re talking about when it comes to performance and ‘low carbs’ and running cells on ketone bodies – so I ‘get it’ you ding-dong. Ketogenic diet…great for treating seizures too, right dopey! Anyhow… I just built that site before my class started this January. It’s growing as the semester passes. ‘Sorry’ I haven’t added a section on performance and ketone bodies to satisfy your lust for details. I choose what I want to write about – I’m not posting a text book online – rather lesson for students in my class. But if you want to learn about electrophysiology, I have a section on that. Thanks for checking my site out Phil! 🙂

Ed, mind your manners. There’s no need to call anyone names.

Ed writes, “Where did you get the idea that I categorically denied ketones as a secondary fuel source?”

You told us you’re interested in teaching the “big picture” of nutrition. I searched for the words “ketone” and “ketogenic” on your website. I found neither there. Yet I see terms like “glycogen depletion” regularly. Somebody in 2014 who doesn’t talk about the impact that a ketogenic metabolism can have on athletic performance is simply missing the boat.

“Ketogenic diet…great for treating seizures too, right dopey!”

That’s way too narrow. A ketogenic diet is great for cognitive function and brain health in general. But odds are low that you paint this part of the “big picture” if you fail to even use the word “ketogenic”.

“Thanks for checking my site out Phil!”

From your website: “The Grand Schematic illustrates the absorption, passage and transformation of every single type of food or fuel substrate used to build and/or power the human body.”

How in heaven’s name could your website not be discussing BOHB and a ketogenic metabolism? If you don’t discuss such things, how could your Grand Schematic possibly be comprehensive?

I checked out the website and found it lacking. Are such things mentioned in the unreadable fine print of that chart, or are they missing?

Does your Grand Schematic talk about how ultramarathoners can win races at a record-breaking pace while consuming only 100 kcal of carbs per hour?

I should have said ‘carbon atoms’ with respect to RQ to satisfy you I suppose since that’s what I tracked. The idea of big picture is moving from general to specific, the value of which science teachers like E.O. Realizes. A schematic can hold only so much information. Same with a website that’s scarcely 90 days old. My claim on my schematic is far less boastful than saying I have produced something ‘perfect’. I understand this is just a good title for a book – and not really literal. But Phil, you ill will is coming out of your ears. Sorry Paul, you dd change your carb content and said: “In our book, we recommend a slightly low-carb diet of 20-30% of calories. If we were re-writing the book now, we would probably be a bit less specific about what carb intake is best. Rather, we would say that a carb intake around 30-40% is neutral and fully meets the body’s actual glucose needs; and discuss the pros and cons of deviating from this neutral carb intake in either direction.” Actual glucose needs – less specific – neutral, whatever.

“I should have said ‘carbon atoms’ with respect to RQ to satisfy you I suppose since that’s what I tracked.”

Your website site uses the words “glucose”, “carbohydrate”, “fat”, and “protein”. If you are talking about ketone bodies, why wouldn’t you use that name? You have no problem using the commonly-accepted name for other molecules; why would you have some quaint name for ketone bodies. 🙄

My conclusion is that you have absolutely no discussion about ketone bodies and a ketogenic metabolism. Am I mistaken? Do you talk about those molecules anywhere on your website?

“My claim on my schematic is far less boastful than saying I have produced something ‘perfect’.”

Does your $1,500 “grand schematic” discuss a ketogenic physiology at all? Unless you discuss this second energy path, your schematic is so far from “perfect” that it’s essentially worthless. You might have been able to publish something that ignored ketone bodies 20 years ago, but not today. If it ignores this essential part of your nutrition, your “grand schematic” is essentially junk.

Does your Grand Schematic talk about how ultramarathoners can win races at a record-breaking pace while consuming only 100 kcal of carbs per hour? If not, why not?

“Thanks for checking my site out Phil!”

You’re welcome. I find the information on your website lacking. I question your expertise to talk about nutritional issues.

That should probably end our dialogue, Ed. Thanks for the conversation.

Somehow you think the omitting ketogenic physiology tantamounts to undermining what the schematic shows. You have nothing but ill-will. New website – 90 days old. What’s your real beef? You just want to fight over ketosis and the conditions around that – a secondary energy source. Moving from general picture to details was my point in the beginning. I maintained discussing ketosis is specific – not general. If you think that’s appropriate for 5-year olds – be my guest and good luck teaching them specifics before general ‘big picture’ stuff. Your semantic war on words is YOUR production. You can’t drop the sword. Keep on going on about ketosis and how I ‘ignored’ it. I GOT it the first time, so what more do you have to say about a schematic you can’t see. It’s blurred to prevent copying. Go ahead and analyze something you can’t read.

“Somehow you think the omitting ketogenic physiology tantamounts to undermining what the schematic shows.”

Tantamounts? 😕 From your website (emphasis mine): “The Grand Schematic illustrates the absorption, passage and transformation of EVERY SINGLE TYPE of food or fuel substrate used to build and/or power the human body.”

You fail to deliver on your grand schematic’s promise. Simple.

“a secondary energy source”

That’s another falsifiable claim. Who says? Ultramarathoners like Timothy Olson are clearly using ketone bodies as their primary energy source.

“If you think that’s appropriate for 5-year olds – be my guest and good luck teaching them specifics before general ‘big picture’ stuff.”

The “big picture” is that there are two energy sources for our bodies. Hybrid cars use two different energy sources, and so do our bodies, and that is the big picture about how we work. The current issue of The Atlantic has an article about 5-year-olds learning Calculus ( http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/03/5-year-olds-can-learn-calculus/284124/ ); this concept of two fuels is far simpler than that.

“Keep on going on about ketosis and how I ‘ignored’ it. I GOT it the first time, so what more do you have to say about a schematic you can’t see.”

If you don’t have the words “ketone” or “ketogenic” anywhere else on your website, odds are vanishingly low that you discuss it in your Grand Schematic. It makes no sense.

Why are you playing games, Ed? Does your chart discuss ketone bodies and a ketogenic metabolism, or not?

Unless you will answer that question, that should probably end our dialogue, Ed. Thanks for the conversation.

Phil, why are you so angry? The bottom section of panels 5,6 ,7 of the schematic illustrate fuel substrate utilization. You forget who you originally referred to ketones as a secondary fuel source, not me. Your anger clouds your thinking. Your words: “I’m not sure how it’s possible to get the “big picture” about nutrition if one doesn’t even mention this secondary energy source.” So bash yourself too while you’re at it. I like using the Toyota Prius as a metaphor to get across the hybrid fuel concept. I’m glad you learned this along the way too. In my section on RER (or RQ) on the schematic – I display one of the bikers Atwater and Benedict stuffed into a room in 1906 to measure carbon balance. This section explains the hybrid nature of the body and ‘all’ the conditions that alter RQ. Including the extremes, stress from being burned, overtraining, ketosis, altering macronutrients, hormonal influence, etc…. Ok, so not all… I guess nothing is perfect, but maybe in your world it is. 🙄 You CAN’T do a word search for ketosis off an image, I’m sure you know that and will not insult you – but I sure as heck gonna please you. I’ve seen your blog; I complimented your work and asked you to drop the sword. Your contnued rant on 5-year olds has turned into cherry picking whatever suits you to vent. I could cherry pick stuff from your blog and vent like you do, I will not spend my time like you. I guess you did not comprehend I said I just built that site and am adding on each week during my lectures and using for my students. But in your world ‘everything’ should be there that suits your fancy.

Again.. ‘who originaly said’ – “a secondary energy source”

YOU did, not me! You’ve used it both ways to suit your bash and have to tell me Timothy uses as a primary source. You’re preaching to the choir. You haven’t found a single mistake on anything in my website… but you’ve made one that deserves rebuke. If you DO find out an actual mistake or error on anything concerning fuel substrate utilization, spelling errors, etc, please search for it and let me know. I don’t care what else you have to say about 5-year olds. But if you have anything instructive about fuel substrate utilization to say, why not create a post on your blog about it? Check out this one from the Harvard Gazette, titled Evolution in Real Timne, bacteria evolve to use citrate as a fuel source! Cool huh?

http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2014/02/evolution-in-real-time/

Now if you can’t play in a likewise fashion, please go away. This is not an olive branch – just drop your sword dude, cuz I dropped mine.

“Phil, why are you so angry?”

I am bothered because you’re playing games in the discussion. You have failed to answer questions I’ve asked you here. I’m interested in a fact-based discussion.

I note a search for ketones/ketogenic are missing from your website, and you tell the discussion: “I should have said ‘carbon atoms’ with respect to RQ to satisfy you” — but you still fail to tell us which page on your website describes ketone bodies as “carbon atoms”. What the heck are you talking about?

“The bottom section of panels 5,6 ,7 of the schematic illustrate fuel substrate utilization.”

So you claim. Based on your lack of the use of the words anywhere else on the website, I doubt it. Your Gut Physiology Schematic fails to mention ketones at all ( http://physicalrules.com/product/gut-physiology-schematic/ ). No mention of these molecules that are produced in muscle cell mitochondria and burned elsewhere in the body. The odds that you cover any of this in your deliberately-blurred chart is remote.

“You have nothing but ill-will.”

I’m interested in a fact-based discussion. I have no interest in an innuendo-based discussion about deliberately-fuzzy charts. And I have no idea what your “carbon molecules” comment went — but you ignored my questions about that.

Have you ever actually sold any of those charts? Is there any public review of your $1,500 chart? Given the lack of discussion elsewhere on your site, why should anyone believe that your chart possibly contains comprehensive and correct information?

If you want to avoid frustration, you would answer the questions I’ve asked in the discussion.

I am curious: why do you think that you couldn’t teach the concept of multiple energy sources to 5-year-olds? Many kids are familiar with Hybrid Cars; that’s the level of detail you’d have to explain to them. If 5-year-olds can get the “big picture” of calculus, explaining the production of ketone bodies should be a slam-dunk. One of the fun things you can tell the kids: many adults do not know that the brain can burn ketones — and that brains tend to run better when using ketone bodies. I am astonished about how many current documents claim that the brain can burn only glucose.

Why do you think you couldn’t teach ketone body physiology to a 5-year-old?

You inject a conclusion into your question people like Michelle Bachmann does does, “why do you think that you couldn’t teach the concept of multiple energy sources to 5-year-olds?” That’s like asking “why do you hate this country?” You are not interested in facts – but instead arguing about what you personally think 5-year olds are capable of learning. I know a gut that can teach binary code to 3rd graders using the Socratic Method; has the imagine aliens that must count on “their two fingers”. Carbon balance is based on RQ. If you don’t know what that is and how it relates to fuel subsrate utilization, then that’s your problem. Not a game. Yes, sold the chart, among other items to the college where I teach. Not a game. I state on the site I will not display it clearly as to prevent copying. You carp over things already defined for good reasons.Again, tell me you are not arguing about what you think is ‘best way to teach kids’ when you say, “Many kids are familiar with Hybrid Cars; that’s the level of detail you’d have to explain to them.” Is that a fact? I agree with you that the metaphor is sufficient, but we are not having a fact based discussion as you claim. You keep on about ketosis – start a thread on your site then if you insist on getting that point across. You’re right – many kids could understand the brain can run in ketones. Ok already. You forgot I originally said kids can learn how glycogen depletion and repletion works and learn a relationship through a liquid filled mannequin. Dependent on the topic points – it’s up to the teacher to choose what other related physiological functions to select. You selected ketosis and running performance to be your bully pulpit. My site is not set up as a blog anyway. I’m using it for lectures. I thought I said that, but it went over your head. I suggest you learn about carbon balance on your own – it may help you find out more facts about thow the body utilizes food.

Last time Phil – to help you with your inadequacy to understand the Grand scheme of metabolism, evidenced by your own admission:

“I have no idea what your “carbon molecules” comment went — but you ignored my questions about that.”

No I did not. All fuel substrate for cells originate in food. Humans ultimately exhale these carbon atoms in the form of CO2. Carbon balance is an ‘ultimate accounting system’ – or one way to look at the totality of energy in energy out. (Not including heat lost, carbon in feces and carbon and lost through fingernail clippings and hair). My schematic illustrates this totality. I don’t think you understand RQ. Here’s a start for you. Google “Lavoisier burns diamonds”. In the 1770’s he used solar power to burn a diamond/carbon. By 1906, Atwater and Benedict accomplished what I have described – mastered a way to measure carbon balance. You should know all this, since you seem so jacked up on ketosis and how the body uses carbon fuel substrates. Didn’t you know that ALL fuel substrate is included in this carbon accounting?

Long ago, I stopped being astonished by the inaccuracies or lack of complete understanding by any author – e.g. the brain utilizes only glucose, classifying lard as a saturated fat when it’s actually more than 50% unsaturated, glucose is the primary fuel for the cells, etc.

I challenge you to provide a simple metaphor for a 5-year old that is effective for teaching the second law of thermodynamics – specifically related to principles of mass gained/lost and heat lost by the body. Then use this to explain why – relative to the body and not a bomb calorimeter – the notion “a calorie is a calorie is a calorie” in terms of mass gain or loss is a falsehood. I can… I bet you can’t. You have failed to understand simple accounting and how it works in terms of the grand scheme – based on carbon balance. If you already understand how the production of heat alters whether the body may gain or lose mass – more power to you. Explain what happens in the cell during these states. Can you do that? I can, I bet you can’t.

The fuzzy section of my schematic shows dried milk briquettes fuel a locomotive train from Chicago to Florida. 1938. Coffee too, was used as fuel in Brazil in a locomotive. This is the section that boils down to covering RQ and everything you demand my schematic must address. I could pack in plenty of extra things that you haven’t even mentioned – by I think white space is necessary for people when looking at illustrations. Go ahead and argue over the use of space too if you want and explain other ways brains can take in information – regardless of age. Should I have included that too on the schematic to satisfy you? Pick and choose man.

Let’s turn things around shall we?

Why do you think brain physiology and running performance is the only way to comprehend the ketogenic state of the body? This is how you go about a fact based discussion. You make up facts with the way you frame a question.

“the most simple thing is for the average person to realize is the body stores a finite amount of glycogen the same way a gas tanks stores gasoline.”

Ed, I disagree. The most simple thing is for an average person just to eat unprocessed foods “to taste” and not worry about macronutrients. I’ve done many self experiments. I’ve eaten 80% carbs and 5% carbs. The only time I noticed an effect was when I was 5% – felt lethargic and worn down. Once I upped carbs to at least 20% (which comes incredibly effortlessly and naturally), I felt no different than I did when I was at 80%. This is all with unprocessed foods.

In fact, I do a simplified version of PHD. I don’t even follow the 50-60%/30%/15% fat/carb/protein split Paul recommends because I’ve stopped worrying about macros. And I’ve felt better than I ever have and my lipids are perfect and my wife is a lot less stressed out being around me.

Of course, my experience comes with the caveat that I am not a high performance athlete. I work a 9-5 job, do light to moderate exercise two days a week.

No doubt Steve, there is a lot of slop factor. We agree. The value of learning “the relationship” of glycogen depletion and repletion is not really about counting carbs – it’s a way of framing a coherent and integrated view on anatomy, food, and energy expenditure – with respect to familiar activities. After all… it took you “many self experiments” – resulting in misery, lethargy, and feeling worn down to establish a relationship – based on ‘eating to taste’. What you described is NOT simple – you painted a picture based on personal experience, and taste. Consider a person, a child even, could have much earlier – understood a simple relationship – then experimented without the lethargy. Fact: Jaminet raised the carb content for the PHD from what’s in his book… for a good reason! You pointed out the main reasons – lethargy and feeling worn down. I guess it wasn’t perfect at the time the book came out. If a person – especially a child grasps the idea “A humming bird needs glucose/carbs to fuel muscles” then a fundamental concept has been learned. Learning to relate to the body, nature, and food is what I’m talking about – not obsessing on perfection or counting carbs. You likely only ‘worried’ about macros – it seems – because you did not understand a simple relationship. The word worry never occurs to people when they already see the folly in the type of experiment you did. (Not to say is was not valuable,instructive, or pointless: YOU needed to satisfy yourself. Irrefutably, going up to 80% and down to 5% undeniably showed you found something out. One extreme sucked – and you ‘felt’ fine at 80% carbs. Go ahead and try the 80% and ‘feeling fine’ for the long term, then see what results! My bet is you and many others will not feel fine.

Ed, we haven’t changed carb recommendations, it’s been at 30% since early 2012.

Ed I think we mostly agree. I am a bit confused though about your criticism of Paul. It seems like you and he are also on a similar wave length because he states in his book that a person should adjust carbs and proteins in accordance to level of athletic activity. In fact, it was from Paul that I ratched up my carbs after my low carb experimental failure.

Also, I still occasionally track my macros just for kicks. I find that if I am eating a variety of PHD compliant whole foods “to taste”, I end up at between 20%-50% carbs depending on the day with an avg that is probably pretty darn close to Paul’s 30% recommendation. I think his recommendations are solid.

Steve, no doubt… the point where a person finally gets/develops a feel, i.e. a sensation – a qualitatively based awareness, e.g. taste, glycogen/water feel in muscles, mental acuity, etc. – is the point where a person may not just stop worrying about macros – but stop worrying about other things like weight, reading nutrition facts labels on processed foods (not food), etc. We hope (in my opinion) to develop and intimate relationship with real food – where nutrition facts labels are not necessary – since we can look at the food itself and identify it with our bodies in a more direct and visceral manner. Taste is a valid way to accomplish this, but in my opinion, misleads too many people (mostly adults who have eaten SAD and blunted their senses) UNTIL they develop a subtle or more refined awareness. The Japanese have a rule to eat until they are 80% full. Anecdote from a Japanese girlfriend of mine who is from Japan. This doesn’t come easy as you know – but if and when it does – you have “arrived”. Visualizing muscles as a reservoir is another way to sense a relationship. A liquid fillable figurine conveys BOTH a qualitative and qualitative way to perceive an energetic relationship – tying in carb intake to carb/glycogen lost – integrating multiple ideas within one anatomical space, the muscles. “Seeing” this makes your 20 to 50% intake ‘swing range’ easy to comprehend – regardless of age. One can see the need to avoid topping off or overfilling glycogen capacity, why it will not happen when eating 20-50% total cals from carbs each day, AND ‘see’ we do not deplete this reservoir when working at a moderate intensity level in a 9-5 job or any other similar situation. I think relating this to muscles and movement is much more visceral than taste – but this is an opinion. People learn differently, different sensations instruct us ‘better’ or not according to our aptitude and conditioning. My biased observations teaching this tell me people more quickly relate to ‘my’ method – or more quickly accept it as a rational method for curbing carb intake to below 50% of total calories – as opposed to basing it on taste. Moreover, any reason to eat more than 50% calories from carbs may be understood, e.g. after sustained high intensity exercise – the stuff at or above lactate threshold. Add frequency to the duration/intensity picture and that expands the idea. Now, I understand, most people are not athletes and many athletes do not sustain such high intensity levels I just described during their training or actual competition. That’s entirely a different discussion. The type Phil pointed out. Finally, we agree Paul’s recommendations are solid. But they could be expanded/refined to explain the upper spectrum of human movement – the intensity range above approx 2/3 VO2 max or at/above lactate threshold. Physics apply – and adjustments follow. It helps to immediately show people the extremes of a spectrum. For example, a friend of mine – a sound technician – does just that. Consider one of the tests for optimizing acoustics in a room. He wants to hear how good the lowest and highest ends sound. Then, tweaking what’s between the extremes is easier to do and understand. Similarly, you yanked your body around from the 5% to 80% range. Now you settled on a method that keeps you between this range – and this range corresponds ‘appropriately’ with your moderate exercise at work.

Good thoughts Ed. I will say based on my personal experience that it is very difficult to get either 80% or 5%. In fact, I think you can only get those levels on extreme diets.

I initially got 80% trying to follow the vegan 80-10-10 diet. It was a full time job to eat that many carbs, let me tell you. And then when I switched to low carb, it was equally neurotic trying avoid simple things like apples.

Since following Paul’s diet, which cuts out many grains and focuses on fruits and safe starches, I find that it is very difficult to go above 50% or below 20%. Eating naturally gets you in that range.

I have eaten around 80 g protein per day for past 5 years and have just been told that I have high potassium levels and chronic kidney disease. I don’t eat root veg or bananas. Don’t know how that happened.

Thank you for posting about this. At least now I don’t have to research that much for my paper. Thanks!

Simply being published means nothing- even in peer reviewed journals. Lots of junk gets published.

What really matters is IF others find your ideas interesting, then THEY take it up, perform experiments… and it WORKS! …And then it gets done more and more by others etc. Then it becomes part of the cannon of science.

Minger is trying to force the evidence of reality to conform with her BELIEFS. This is a NO-NO. In scientific matters, we MUST make our beliefs CONFORM to the evidence of reality.

Far too many Bloggers do NOT understand how science is done and do not allow for the BIASES we allll have. Science is a human endeavor and invention. It has ALLL the same poltics, shenanigans and biases etc. that ALL human endeavors have….

It is TOTAL NONSENSE to claim otherwise as astrophysicist , Paul Davies , points out.

Then by extension, the cannon of science is filled with junk… and when ‘it’ gets done more and more by others, the junk multiplies. Tweaking out ‘how it works’ or seems to work, e.g. altering hypothesis to fit data or vice versa is definitely a reality – a reflection of the shenanigans, biases, etc. no? So how do you know when your beliefs are full of falsehoods because you made ‘them conform’ to the ‘evidence of reality’ – which you know darn well is tainted by the biases, politics, etc.?

Scientists are all biased as Paul Davies point out. Yes. But they try to work around it- the better ones.

Overall, i can see you do not understand science, Neither does Colpo , nor most Bloggers….

Replicated A1A quality experiments from numerous different research groups finding the same thing. Many independent test methods getting the same result enhance it even further, as is the case of Dark Matter and Dark Energy.

THAT is science- NOT simply “being published in the peer reviewed literature.”

The Principia by Newton was NOT peer reviewed, yet very excellent science…..

Most scientific ideas are wrong, Ed. This is not taught enough.

The replication from A1A experiments separates the peer reviewed JUNK from the science. Junk gets by the referees.

Experiments smooth it out. General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics are well tested by experiment. A1A experiment replicated by numerous research labs over and over for years.

Ed,

You would do well to get off of the Blogosphere sites and ON to Dr. Alex Filippenko lectures to understand how science works…… You would learn a lot as would most of the dopey Bloggers.

You did not comprehend I was talking about epistemology. Dopey; you. Brush up on reading and comprehension – you essentially repeated what I was saying in a direct way. Yep.. when Newton inserted a yarning needles into his eye (not piercing it, so you understand what I’m saying literally Raz)… he indeed was conducting science as he observed spectrum of light directly. Observation is the heart of science. Bias issue is obvious surface for you to whine about – what is not is the awareness of your conditioning influences – hence – how do you know what you know… etc. You should look the word epistemology up if you fail to understand its meaning. “Raz”

You have a CHILDISH understanding of science. Look into SUSSKIND.

What about the current research and approach of Dr. David Perlmutter who suggests one eat no more than 60 grams of CHO a day (not including athletes)? From what I see he has good research backing up the nueuroprotective benefits of eating this way, even for currently healthy people.