Since we’ve started the topic of weight loss, it seems a good time to discuss the sort of dessert one should eat while on a calorie-restricted diet.

Almost any mix of a carbohydrate with a fat can serve as a dessert. Sweeter desserts use more sugar, less starch.

The following principles can guide the design of a Perfect Health Diet weight loss dessert:

- Ketogenic fats, such as those in coconut oil, are the best fat source. Ketones can evade certain kinds of metabolic damage, lower blood sugar levels, contribute to metabolic recovery.

- Dieters should maintain their regular carbohydrate and protein consumption, since the recommended Perfect Health Diet amounts are calibrated to meet nutritional needs and malnutrition must always be avoided.

- Dieters should avoid fructose, a toxin. Carbs are best obtained from starches or from fructose-free sugars like dextrose (the monosaccharide of glucose) or maltose (the disaccharide of glucose).

Here’s one dessert that meets those guidelines. It’s a common Asian-Pacific dessert: Taro Coconut Cream Soup.

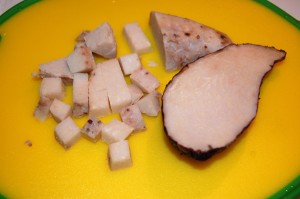

First, gather your starches. Here we’re dicing some (already cooked) taro that was leftover from dinner:

Tapioca pearls make another nice addition to the soup. They are white before cooking, but will become transparent when fully cooked:

Put a can of coconut milk in a pot and warm it to the boiling point. You can add up to an equal amount of water if you prefer a less thick soup:

Add tapioca pearls and taro, and simmer for 10-15 minutes until the tapioca pearls are transparent. You may need to stir from time to time to make sure nothing sticks to the bottom:

Once it’s warm and the pearls are cooked, transfer some to a bowl. Here Paul has added a bit of coconut oil for some extra fat, some lemon juice, and cinnamon:

Lemon juice is beneficial to health, for reasons we’ll explain in an upcoming series on enhancing immune function. Lemon juice adds sweetness but has only 7 calories per fluid ounce. Cinnamon increases insulin sensitivity, which is probably desirable for weight loss. Both add to the flavor of the dessert.

There it is – a Perfect Health Diet dessert for those on a diet!

Shou-Ching is not on a diet, and decided to sweeten hers with some clover honey. She also included some leftover sweet potato chunks:

An Aside About Sweet Potatoes

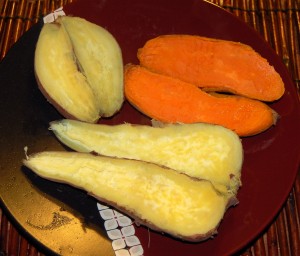

Last week we had a discussion about different kinds of sweet potatoes and yams. So we bought a sampling. Here, clockwise from upper right, are an American sweet potato (orange), a Korean sweet potato (large and yellow), and a Japanese sweet potato (small and yellow). The last two are botanically yams, not sweet potatoes; they are starchy and not nearly as sweet as the American sweet potato.

The Korean sweet potato is what we eat; it has a pleasant chestnut flavor. I thought the Japanese sweet potato was excellent also. American sweet potatoes are too sweet for my taste.

Recent Comments