First, thank you to everyone who commented on the quiz. I enjoyed reading your thoughts.

Is High LDL Something to Worry About?

Perhaps this ought to be the first question. Jack Kronk says “I don’t believe that high LDL is necessarily a problem” and Poisonguy writes “Treat the symptoms, Larry, not the numbers.” Poisonguy’s comment assumes that the LDL number is not a symptom of trouble. Is it?

I think so. It helps to know a little about the biology of cholesterol and of blood vessels.

When cells in culture plates are separated from their neighbors and need to move, they make a lot of cholesterol and transport it to their membranes. When cells find good neighbors and settle down, they stop producing cholesterol.

The same thing happens in the body. Any time there is a wound or injury that needs to be healed, cholesterol production gets jacked up.

When people have widespread vascular injuries, cholesterol is produced in large quantities by cells lining blood vessels. Now, to repair injuries cells have to coordinate their functions. Endothelial cells are the coordinators of vascular repair: they direct other cell types, like smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, in the healing of vascular injuries.

To heal vascular injuries, these cells not only need more cholesterol for movement; they also need to multiply. It turns out that LDL, which carries cholesterol, also causes vascular cells to reproduce (“mitogenesis”):

The best-characterized function of LDLs is to deliver cholesterol to cells. They may, however, have functions in addition to transporting cholesterol. For example, they seem to produce a mitogenic effect on endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts, and induce growth-factor production, chemotaxis, cell proliferation, and cytotoxicity (3). Moreover, an increase of LDL plasma concentration, which is observed during the development of atherosclerosis, can activate various mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways …

We also show … LDL-induced fibroblast spreading … [1]

If endothelial cells are the coordinators of vascular repair, and LDL particles their messengers to fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells, then ECs should be able to generate LDL particles locally. Guess what: ECs make a lipase whose main effect is to decrease HDL levels but can also convert VLDL and IDL particles into LDL particles and remove fat from LDL particles to make them into small, dense LDL:

Endothelial lipase (EL) has recently been identified as a new member of the triglyceride lipase gene family. EL shares a relatively high degree of homology with lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase …

In vitro, EL has hydrolyzed phospholipids in chylomicrons, very low density lipoprotein (VLDL), intermediate density lipoprotein and LDL. [2]

Immune cells, of course, are essential for wound healing and they should be attracted to any site of vascular injury. It turns out that immune cells have LDL receptors and these receptors may help them congregate at sites of vascular injury. [3]

I don’t want to exaggerate the state of the literature here: this is a surprisingly poorly investigated area. But I believe these things:

1. Cholesterol and LDL particles are part of the vascular wound repair process.

2. Very high LDL levels are a marker of widespread vascular injury.

Now this is not the “lipid hypothesis.” Compare the two views:

- The lipid hypothesis: LDL cholesterol causes vascular injury.

- My view: LDL cholesterol is the ambulance crew that arrives at the scene of the crime to help the victims. The lipid hypothesis is the view that ambulance drivers should be arrested for homicide because they are commonly found at murder scenes.

So, to Poisonguy, on my view high LDL numbers are a symptom of vascular injury and are a cause for concern.

Big-Picture View of the Cause of High LDL

So, on a micro-level, I think vascular damage causes high LDL. But what causes vascular damage?

Here I notice a striking difference in commenters’ perspectives and mine. I tend to take a big-picture, top-down view of biology. There are three basic causes of nearly all pathologies:

1. Toxins, usually food toxins.

2. Malnutrition.

3. Pathogens.

The whole organization of our book is dictated by this view. It is organized in four Steps. Step One is about re-orienting people’s views of macronutrients away from high-grain, fat-phobic, vegetable-oil-rich diets toward diets rich in animal fats. The other steps are about removing the causes of disease:

1. Step Two is “Eat Paleo, Not Toxic” – remove food toxins.

2. Step Three is “Be Well Nourished” – eliminate malnutrition.

3. Step Four is “Heal and Prevent Disease” – address pathogens by enhancing immunity and, where appropriate, taking advantage of antibiotic therapies.

So when someone offers a pathology, any pathology, my first question is: Which cause is behind this, and which step do they need to focus on?

In Larry’s case, he had been eating low-carb Paleo for years. So toxins were not a problem.

Pathogens might be a problem – after all, he’s 64, and everybody collects chronic infections which tend to grow increasingly severe with age – but Larry hadn’t reported any other symptoms. More to the point, low-carb Paleo diets typically enhance immunity, yet Larry had fine LDL numbers before adopting low-carb Paleo and then his LDL got worse. So it wouldn’t be infectious in origin unless his diet had suppressed immunity through malnutrition – in which case the first step would be to address the malnutrition.

Step Three, malnutrition, was the only logical answer. The conversion to Paleo removes a lot of foods from the diet and could easily have removed the primary sources of some micronutrients.

So I was immediately convinced, just from the time-course of the pathology, that the cause was malnutrition.

Micronutrient Deficiencies are Very Common

In the book (Step Three) we explain why nearly everyone is deficient in micronutrients. The problems are most severe for minerals: water treatment removes minerals from water, and mineral depletion of soil by industrial agriculture leads to mineral deficiencies in farmed plants and grain-fed animals.

This is why our “essential supplements” include a multimineral supplement plus additional quantities of five minerals – magnesium, copper, chromium, iodine, and selenium. Vitamins get a lot of attention, but minerals are where the big health gains are.

Copper Deficiency and LDL

Some micronutrient deficiencies are known to cause elevated LDL.

Readers of our book know that copper causes vascular disease; blog readers may be more familiar with an excellent post by Stephan, “Copper and Cardiovascular Disease”, discussing evidence that copper deficiency causes cardiovascular disease. As I’ve just argued that cardiovascular disease causes high LDL, it shouldn’t be a surprise that copper deficiency also causes hypercholesterolemia:

Copper and iron are essential nutrients in human physiology as their importance is linked to their role as cofactors of many redox enzymes involved in a wide range of biological processes, as well as in oxygen and electron transport. Mild dietary deficiencies of both metals … may cause long-term deleterious effects in cardiovascular system and alterations in lipid metabolism (3)….

Several studies showed a clear correlation among copper deficiency and dyslipidemia. The main alterations concern higher plasma CL and triglyceride (TG) concentrations, increased VLDL-LDL to HDL lipoproteins ratio, and the shape alteration of HDL lipoproteins. [4]

The essentiality of copper (Cu) in humans is demonstrated by various clinical features associated with deficiency, such as anaemia, hypercholesterolaemia and bone malformations. [5]

Over the last couple of decades, dietary copper deficiency has been shown to cause a variety of metabolic changes, including hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, and glucose intolerance. [6]

Copper deficiency is, I believe, the single most likely cause of elevated LDL on low-carb Paleo diets. The solution is to eat beef liver or supplement.

So, was my advice to Larry to supplement copper? Yes, but that was not my only advice.

Other Micronutrient Deficiencies and Elevated LDL

Another common micronutrient deficiency that causes elevated LDL cholesterol is choline deficiency that is NOT accompanied by methionine deficiency. That is discussed in my post “Choline Deficiency and Plant Oil Induced Diabetes”:

Choline deficiency (CD) by itself induces metabolic syndrome (indicated by insulin resistance and elevated serum triglycerides and cholesterol) and obesity.

A combined methionine and choline deficiency (MCD) actually causes weight loss and reduces serum triglycerides and cholesterol …

I quote both these effects because it illustrates the complexity of nutrition. A deficiency of a micronutrient can present with totally different symptoms depending on the status of other micronutrients.

Julianne had a really nice comment, unfortunately caught in the spam filter for a while, with a number of links. She mentions vitamin C deficiency and, with other commenters, noted the link between hypothyroidism and elevated LDL. As one cause of hypothyroidism is iodine or selenium deficiency, this is another pathway by which mineral deficiencies can elevate LDL.

UPDATE: Mike Gruber reduced his LDL by 200 mg/dl by supplementing iodine. Clearly iodine can have big effects!

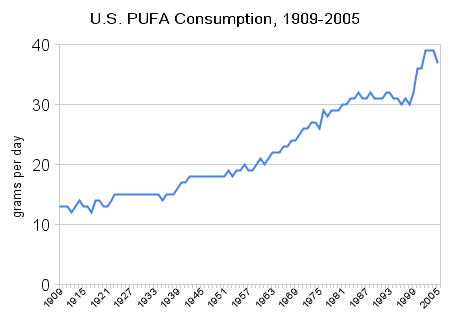

Other commenters brought up fish oil. They may be interested to know that fish oil not only balances omega-6 to modulate inflammatory pathways, it also suppresses endothelial lipase and thus moderates the LDL-raising and HDL-lowering effect of vascular damage:

On the other hand, physical exercise and fish oil (a rich source of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) suppress the activity of EL and this, in turn, enhances the plasma concentrations of HDL cholesterol. [7]

Whether this effect is always desirable is a topic for another day.

My December Advice to Larry

So what was my December advice to Larry?

It was simple. In adopting a low-carb Paleo diet, he had implemented Steps One and Two of our book. My advice was to implement Step Three (“Be well nourished”) by taking our recommended supplements. Eating egg yolks and beef liver for copper and choline is a good idea too.

Just to cover all bases, I advised to include most of our “therapeutic supplements” as well as all the “essential supplements.”

Since December, Larry has been taking all the recommended supplements and eating 5 ounces per week of beef liver. As I noted yesterday, Larry’s LDL decreased from 295 mg/dl to 213 mg/dl, HDL rose from 74 mg/dl to 92 mg/dl, and triglycerides fell from 102 to 76 mg/dl since he started Step Three. This is all consistent with a healthier vasculature and reduced production of endothelial lipase.

Conclusion

Some people think there is something wrong with a diet if supplements are recommended. They believe that a well-designed diet should provide sufficient nutrition from food alone, and that if supplements are advised then the diet must be flawed.

I think this is quite mistaken. The reality is that Paleolithic man was often mildly malnourished, and modern man – due to the absence of minerals from treated water and agriculturally produced food, and the reduced diversity and higher caloric density of our foods – is severely malnourished compared to Paleolithic man.

We recommend eating a micronutrient-rich diet, including nourishing foods like egg yolks, liver, bone broth soups, seaweed, fermented vegetables, and so forth. But I think it’s only prudent to acknowledge and compensate for the widespread nutrient depletion that is so prevalent today. Even when nutrient-rich food is regularly eaten, micronutrient deficiencies are still possible.

Eating Paleo-style is not enough to guarantee perfect health. Luckily, supplementation of the key nutrients that we need for health and that are often missing from foods will often get us the rest of the way.

References

[1] Dobreva I et al. LDLs induce fibroblast spreading independently of the LDL receptor via activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. J Lipid Res. 2003 Dec;44(12):2382-90. http://pmid.us/12951358.

[2] Paradis ME, Lamarche B. Endothelial lipase: its role in cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2006 Feb;22 Suppl B:31B-34B. http://pmid.us/16498510.

[3] Giulian D et al. The role of mononuclear phagocytes in wound healing after traumatic injury to adult mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 1989 Dec;9(12):4416-29. http://pmid.us/2480402.

[4] Tosco A et al. Molecular bases of copper and iron deficiency-associated dyslipidemia: a microarray analysis of the rat intestinal transcriptome. Genes Nutr. 2010 Mar;5(1):1-8. http://pmid.us/19821111.

[5] Harvey LJ, McArdle HJ. Biomarkers of copper status: a brief update. Br J Nutr. 2008 Jun;99 Suppl 3:S10-3. http://pmid.us/18598583.

[6] Aliabadi H. A deleterious interaction between copper deficiency and sugar ingestion may be the missing link in heart disease. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(6):1163-6. http://pmid.us/18178013.

[7] Das UN. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, endothelial lipase and atherosclerosis. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005 Mar;72(3):173-9. http://pmid.us/15664301.

Recent Comments