The results from the Perfect Health Retreats continue to surprise me.

Retreat attendees come for all sorts of reasons. In terms of weight, they have so far had a fairly similar profile to the general middle-aged population, with almost half being obese and another quarter overweight. That’s enough obese and overweight participants to give us insight into the effects of our advice for weight loss.

Weight Loss Experience at the Perfect Health Retreat

When I was preparing my Ancestral Health Symposium talk on weight loss, I noticed a remarkable pattern that I didn’t have time to discuss in my talk. The pattern was that the amount of weight loss during retreats was proportional to the excess weight of the participants.

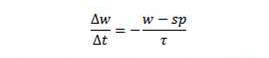

Here are some charts, with the amount of weight loss during the retreat plotted against BMI. From our 2013 retreats, which lasted 30 days, I’ve plotted just the obese participants:

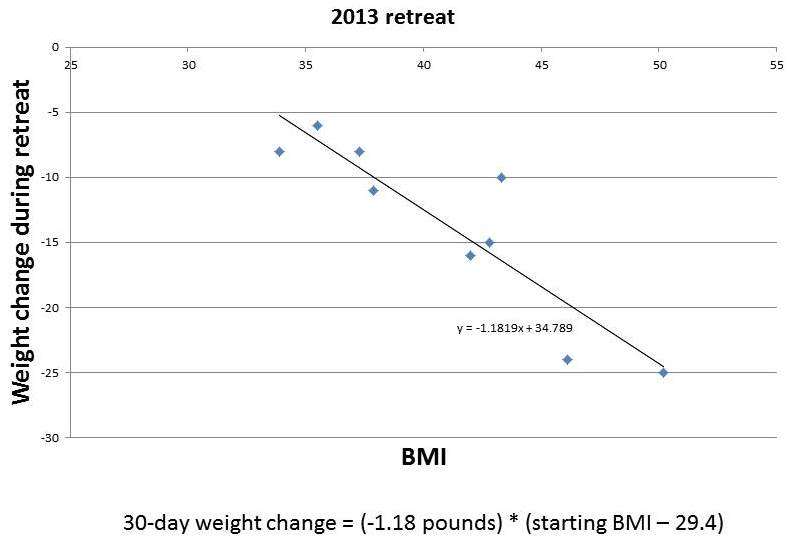

And from our May 2014 retreat, which lasted two weeks, I’ve plotted the obese and overweight participants:

You can see that the amount of weight lost in this short period is roughly proportional to starting BMI. It tracks remarkably closely to a straight line. I’ve put the equations for the lines underneath each figure.

If weight loss follows these straight lines, then you can easily envision what would happen to someone with a high starting BMI, say 50, who lived at the retreat permanently. He would lose weight rapidly at first. As his weight (and BMI) declined, his rate of weight loss would slow, tracking the line. As he approached a destination BMI in the 20-29 range, his rate of weight loss would approach zero. His weight would stabilize at this destination BMI.

(Parenthetically, let me comment on a few features of the charted data. First, it doesn’t surprise me that the destination BMI in the 2013 retreats was higher than that in the 2014 retreats; our program was still under development in 2013, the retreats are much more optimized now; for example, the 2013 retreats were held in a rather dimly lit facility with few windows, yet we know that circadian rhythm entrainment is huge for weight loss. Second, it doesn’t surprise me that the 2014 data is noisier than the 2013 data; the shorter retreat means that other factors, such as jet lag from traveling to the retreat, influence outcomes more significantly; also, in May 2014 we didn’t weigh anyone at the retreat so weights were self-reported from home by guests, making the weights not as reflective of the retreat environment and the time between weighings somewhat variable. Third, it doesn’t surprise me that the rate of weight loss at the 2014 retreat was slower than at the 2013 retreat; 2014 retreat participants were explicitly encouraged not to restrict calories, and wine, snacks, and desserts were served daily, whereas in 2013 the proprietor encouraged some calorie restriction and did not serve alcohol.)

The destination BMIs – the weights at which the fitted lines indicate weight loss would stop – are remarkably close to normal weight.

Implications for a Body Weight “Set Point”

Obesity researchers have found the concept of a body weight “set point” to be useful in explaining obesity. However, they generally find that the “set point” is well above normal weight, even after weight loss interventions.

Our Perfect Health Retreat weight loss experiences are consistent with the existence of a set point. However, Retreat experiences are best understood as telling us that:

- The body has a desired weight – a set point – that weight inexorably migrates toward.

- The pressure or force driving weight change, as indicated by the rate of weight change, is proportional to the deviation of actual weight from the set point. A larger deviation from the set point creates a greater pressure for weight change and a more rapid migration toward the set point. As the set point is approached, the rate of weight change slows down.

- In the context of our retreats, in which people follow the Perfect Health diet and lifestyle, the set point is reset to a normal weight within a few days of their arrival at the retreat.

If PHD does indeed reset the set point to normal in a few days, it is consistent with the theme of my Ancestral Health Symposium talk: it is diet and lifestyle that determine weight; fix those and your weight will inexorably normalize.

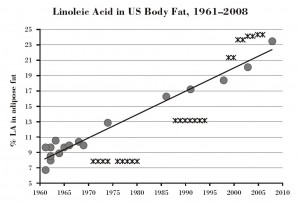

But this conclusion is radically contrary to the beliefs of academic obesity researchers. The general view is that changing the set point is extremely difficult, in part because the determinants of the set point extend back in time many decades:

Your heredity and your environment-starting back at the moment of your conception-determine your set point. Over the long term, excess food and insufficient exercise will override your body’s natural tendency to stay at its set point and lead to a higher, less healthy set point.

This implies that normalizing the set point will also require years or decades, because that is how long it takes for the influence of past set-point-raising factors to expire.

The Center for the Study of Nutrition Medicine, led by the distinguished obesity researcher George Blackburn, advises that one can’t sustainably lose more than 10% of body weight in six months:

Scientific evidence supports losing no more than 10% of your body weight at a time. It turns out that the body’s set point and its many regulatory hormones dictate the effectiveness of the 10% loss. That’s the amount of weight you can lose before your body starts to fight back. Many clinical studies have confirmed this phenomenon. Of course, some people can lose more than 10% at a time, but precious few can then maintain that loss.

After you maintain your new, lower weight for 6 months, you can repeat the cycle and reset your set point again by losing another 10%.

Is Dr. Blackburn’s conclusion, confirmed by “many clinical studies,” valid for PHDers? To test that, we need a longer time series.

The largest weight losses at the Perfect Health Retreat have been about 10% of body weight in 30 days. If Dr. Blackburn is right, then after people on PHD lose 10% of the body weight – i.e., after one or two months on PHD – then we should see weight loss stall or enter a yo-yo pattern for the remainder of six months, until the set point adjusts lower and weight loss can resume.

Alternatively, if PHD immediately and permanently resets the set point to a normal weight, the rate of weight loss in PHDers should track a straight line just like in the retreat data. We should see continuous weight loss with no stalls – although there will be a steady slowing of weight loss as a normal weight is approached. In the long run, weight is normalized permanently, and there is no weight regain as long as the person remains on PHD.

Which is it?

The long-term pattern of weight loss on PHD

Fortunately we have a few cases in which PHD readers have faithfully followed our advice, tracked their weight closely, and shared the data with us.

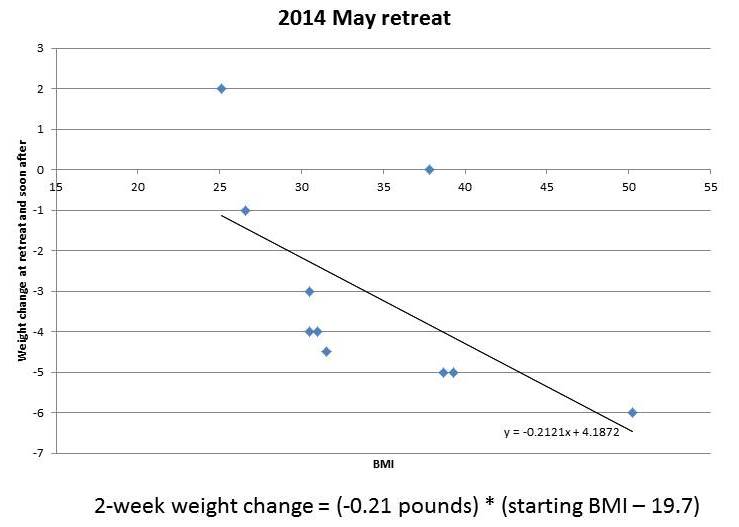

Before I discuss their weight loss experiences, let me describe the weight loss path we would expect to see if the pattern observed at the retreats holds up. The weight loss pattern observed at the retreats is described in a simple equation:

Those of you who took calculus will recognize that as a differential equation which we can integrate. It leads to the following formula for weight as a function of time:

So if PHD is really re-setting the set point to a normal weight within a few days, after which the set point doesn’t change — it just stays at the same weight, normal — then we should see weight loss follow this exponential decay.

OK, now let me get to cases.

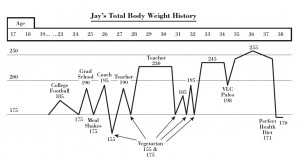

The case of Jay Wright

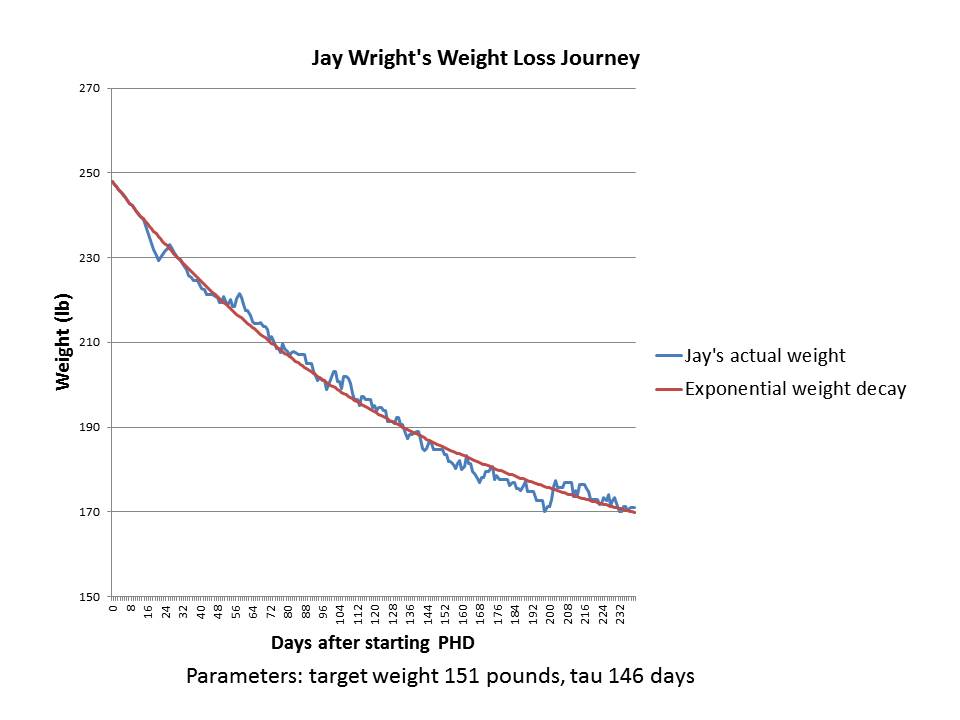

Previously on this site we discussed Jay Wright’s weight loss journey. Here is his weight in blue, and I’ve fitted an exponential decay to it in red:

It’s a pretty good fit with a set point of 151 pounds and a characteristic time of 146 days.

Jay’s weight loss took place in 2011. In several years since then, his weight has remained stable around 170 pounds. I believe Jay’s height is 5’10”, so his BMI at 170 pounds is 24.4 and his BMI at the fitted target weight of 151 pounds would have been 21.7.

As you can see by reading Jay’s story, during his period of weight loss he was intentionally restricting calories to 1200 calories per day; but when he got to his goal weight of 170-175 pounds he stopped restricting calories and ate to appetite. I’ll speculate that intentional calorie restriction may lower the set point by a few BMI points, say from 24.4 to 21.7, so that Jay’s “set point” during his weight loss period was 151 pounds but it reverted to 170 pounds once he began eating ad libitum.

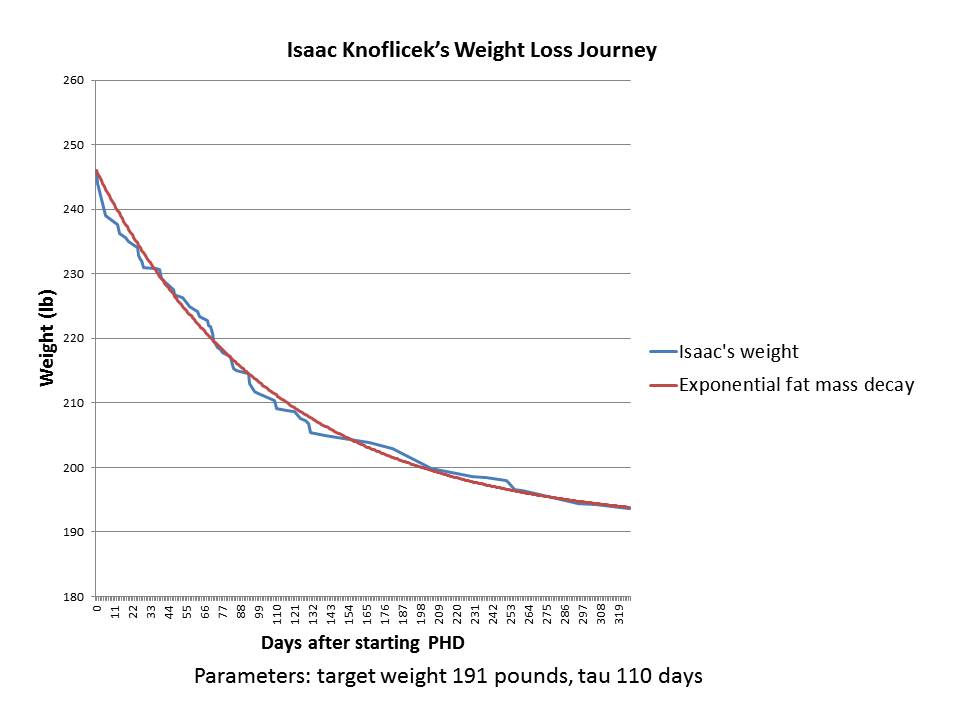

The case of Isaac Knoflicek

Our second case was posted by Isaac Knoflicek on the PHD Facebook group a few weeks ago. Here was his weight loss chart. He described it this way:

~110 lost, first chunk was bike commuting, then after about a year of that I started PHD and the weight came off like crazy.

Isaac gave me his weight loss data. Here is what happened after he began PHD:

As you can see, it’s a great fit to an exponential decay – an even better fit than in Jay’s case.

Isaac is 6’3” (190.5 cm) tall, so the target weight of 191 pounds is a BMI of 23.9 – absolutely normal.

Although Isaac’s data ended in early 2013, he wrote, “I’ve spent the last year and a half making smaller tweaks but generally staying around the same weight.” That’s consistent with him having gotten close to his target weight; and with his set point having been permanently reset to a normal weight, so that there is no biological pressure for weight regain.

Here are Isaac’s before and after photos:

Implications

Every obese person who has come to our retreats has lost weight (save one whose weight was unchanged), and in most cases weight loss tracked closely to the same pattern for all participants: a linear relationship between weight loss rate and starting BMI. The line reaches a zero weight loss rate near a normal BMI.

The implication is that for nearly all retreat participants, PHD actually fixes all the factors of overweight or obesity and leads to a normalization of the body weight set point. Although our experience at the retreats is still limited, the statistics are good enough to infer that PHD should work for most, if not all, non-diabetic obese people.

Another implication is that it’s possible to normalize set point in just a few days. If set point wasn’t normalized in a few days, weight loss rates over a 14-day retreat could not track a straight line.

Very likely, the reason the set point has appeared persistently high to academic researchers is that the weight loss approaches they have studied don’t actually address most factors in obesity. My Ancestral Health Symposium talk explains that weight is set by a multifactorial process and if multiple obesogenic factors are left uncorrected, the set point will remain elevated.

A third implication is that there is a characteristic physiological time for weight loss, and it may not be possible to accelerate weight loss much. The fastest rate of weight loss we observe is about 4 months to move 63% of the way toward normal weight from current weight. Based on rates of weight loss at the retreats, 6 to 8 months is more typical.

Fourth, it’s not obvious that calorie restriction is either necessary or desirable for long-term weight loss. If all calorie restriction does is temporarily lower the set point by a few BMI points, without affecting the characteristic time for weight loss τ, then calorie restriction may have little effect on either the ultimate weight or on how long it takes to reach it. Calorie restriction may be an energy-sapping, misery-inducing tactic that succeeds only in reducing weight slightly for a few months, with no long-term benefit. And it may have health risks.

Finally, the “last ten pounds problem” has produced a lot of angst. People often lose weight successfully to a weight about 10 pounds above their personal target, then find it extremely difficult to lose the last 10 pounds. We can now see why the last ten pounds can be so hard to lose. First, any minor defect in diet or lifestyle may raise the set point slightly. Second, weight generally rises with age, and people may use their younger weights as targets; so they may be underestimating their body’s physiological weight target. But mainly, it may just be that weight loss becomes very slow once you are within ten pounds of the set point. At 10 pounds above the set point, it takes 6 months to lose 6 pounds, even if you do everything perfectly. That’s only 1 pound per month. From 4 pounds above the set point, it takes 6 months to lose another 2.4 pounds – only 0.4 pounds per month. Then the pace of weight loss slows further. Once the rate of weight change slows to 0.1 pounds per week or less, it will appear to have gone to zero.

Conclusion

To convince skeptics, we will need more data. But I’m going to jump directly to these conclusions:

- For most people, PHD (including both diet and lifestyle practices) will cure obesity – in the sense of normalizing body weight set point – in a few days.

- Although the set point is normalized almost immediately, weight loss takes time. Even if you do everything perfectly, it takes about 6 months to shed 63% of excess weight, a year to lose 86%, 18 months to lose 95%, and 2 years to lose 98%. The last few pounds take a long time to go away.

Curious if I’m right? If you are overweight and would like to test this personally, come to our retreats and help us generate more data.

Recent Comments