Last week in An Anti-Cancer Diet (Sep 28, 2011), I recommended that cancer patients eat 400 to 600 carb calories per day, but combine it with a program of daily intermittent fasting plus longer “ketogenic fasts” and periods of ketogenic dieting or low-protein dieting to promote autophagy.

The recommendation to eat some carbohydrates, plus my statement that it was possible for cancer patients to develop a “glucose deficiency” which might promote metastasis and the cancer phenotype, seems to have stirred a bit of a fuss.

In addition to making @zooko sad, it led Jimmy Moore to reach out to a number of gurus to ask their opinion. On Twitter, Jimmy says:

Working on an epic blog post today about @pauljaminet and his “safe starches” concept. Input from numerous #Paleo and #lowcarb peeps.

I’m excited to have this discussion. As Jimmy later tweeted:

Should be fun to hash all this out publicly for ALL of us to understand better about your concepts. Here’s to education.

So far, I have seen responses from Dr. Kurt Harris and Dr. Ron Rosedale. On PaleoHacks, there is an extensive discussion on a thread started by Meredith.

UPDATE: Jimmy’s post is up: Is There Any Such Thing as “Safe Starches” on a Low-Carb Diet?.

I think this discussion is wonderful. With so many people putting effort into this, I have an obligation to respond. I’ll start with Kurt’s perspective today, then Ron Rosedale’s early next week, then whoever else participates in Jimmy’s epic post.

PHD and Archevore: Similar Diets

Kurt and I have essentially identical dietary prescriptions. However, our reasoning sometimes works from different premises. Kurt observes:

My arguments are based more on ethnography and anthropology than some of Paul’s theorizing, but I arrive at pretty much the same place that he does.

An example of a point of agreement is Kurt’s endorsement of glucose-based carbs:

[I] see the human metabolism as a multi-fuel stove, equally capable of burning either glucose or fatty acids at the cellular level depending on the organ, the task and the diet, and equally capable of depending on either animal fats or starches from plants as our dietary fuel source …

We are a highly adaptable species. It is not plausible that carbohydrates as a class of macronutrient are toxic.

I think that if there is no urgency about generating ATP then fatty acid oxidation is slightly preferable to glucose burning. But essentially, I share Kurt’s point of view. Our ancestors must have been well adapted to consuming high-carb diets, and necessity surely thrust such diets upon some of our ancestors. Certainly there’s no reason why consuming starch per se should be toxic.

Kurt and I also agree on which starches are safe:

These starchy plant organs or vegetables are like night and day compared to most cereal grains, particularly wheat. One can eat more than half of calories from these safe starches without the risk of disease from phytates and mineral deficiencies one would have from relying on grains.

White rice is kind of a special case. It lacks the nutrients of root vegetables and starchy fruits like plantain and banana, but is good in reasonable quantities as it is a very benign grain that is easy to digest and gluten free.

We agree that safe starches are a more useful part of the diet than fruits and vegetables:

[E]ating starchy plants is more important for nutrition than eating colorful leafy greens …

I view most non-starchy fruit with indifference. In reasonable quantities it is fine but it won’t save your life either. I like citrus now and then myself, especially grapefruit. But better to rely on starchy vegetables for carbohydrate intake than fruit.

We agree on the optimal amount of carbs to eat:

I personally eat around 30% carbohydrate now and have not gained an ounce from when I ate 10-15% (and I have eaten as high as 40% for over a year also with zero fat gain) If anything I think even wider ranges of carbohydrate intake are healthy.

One can probably eat well over 50% of calories from starchy plant organs as long as the animal foods you eat are of high quality and micronutrient content.

I think being slightly low-carb, in the sense of eating slightly below the glucose share of energy utilization which I estimate at about 30% of energy, is optimal. However, I think we are metabolically flexible enough that a very broad range of carb intake may be nearly as good. I would consider 10% a minimal but healthy intake of carbs, and 50% a higher-than-optimal, but still healthy, intake so long as the carbs are “safe” and the diet is nourishing.

Differing Origins of Our Ideas

Kurt mentions that his ideas are more derived from ethnography and anthropology than mine.

I give great weight to evolutionary selection as an indicator of the optimal diet, and am friendly to ethnographic and anthropological arguments. If I don’t give tremendous weight to such arguments, it’s because I think some other lines of argument give us finer evidence about the optimal diet.

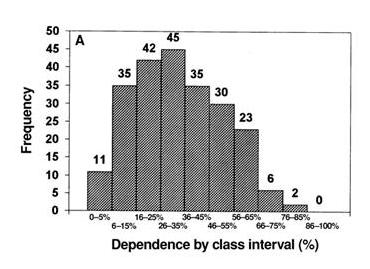

Here, from a paper by Loren Cordain et al [1], are representations of hunter-gatherer diets:

The top graph shows plant food consumption by calories, the bottom graph animal+fish consumption by calories. The numbers are how many of 229 hunter-gatherer societies ate in that range. Typically, hunter-gatherers got 30% of calories from plant foods and 70% of calories from animal foods.

I think the Cordain et al data supports my argument that obtaining 20% to 30% of calories from carbs is probably optimal. However, it’s hardly decisive. There is considerable variability, mainly in response to food availability in the local environment. Inuits, who had few edible plants available, ate hardly any plant foods; tropical tribes with ready access to starchy plants, fruits, and fatty nuts sometimes obtained a majority of calories from plants.

Hunter-gatherer diets, therefore, are a compromise between the diet that is healthy and the diet that is easy to obtain. A skeptic could argue that hunter-gatherers routinely ate a flawed diet because some type of food was routinely easier to obtain than others, and thus systematically biased the diet.

I believe evidence from breast milk is both more precise about what diet is optimal, and much harder for skeptics to refute. Breast milk composition is nearly the same in all humans worldwide, and it has been definitely selected to provide optimal nutrition to infants.

So breast milk, I think, gives us a much clearer indication of the optimal human diet than hunter-gatherer diets. It is an evolutionary indicator of the optimal diet, but it is not ethnographic or anthropological.

There are other evolutionary indicators of the optimal diet — mammalian diets, for instance, and the evolutionary imperative to function well during a famine — which, as readers of our book, we also use to determine the Perfect Health Diet. So, while I think ethnographic and anthropological findings give us important clues to the optimal diet, I think there are plenty of other sources of evidence to which we should give weight. Fortunately, all of these sources of insight seem to be consistent in supporting low-carb animal-food-rich diets — a result which is gratifying and should give us confidence.

Food Reward and Obesity

Kurt seems to have been more persuaded than I am by Stephan Guyenet’s food reward hypothesis (which is, of course, not of Stephan’s creation – it is the dominant perspective in the community of academic obesity researchers). Kurt writes:

Low carb plans have helped people lose fat by reducing food reward from white flour and excess sugar and maybe linoleic acid. This is by accident as it happens that most of the “carbs” in our diet are coming in the form of manufactured and processed items that are simply not real food. Low carb does not work for most people via effects on blood sugar or insulin “locking away” fat. Insulin is necessary to store fat, but is not the main hormone regulating fat storage. That would be leptin.

I agree with Kurt in rejecting what he calls the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, but I am uneasy at the confident assertion that “reducing food reward” is the mechanism by which excluding flour, sugar, and omega-6 fats helps people lose weight.

Let me say first that there is no doubt that the brain has a food reward system that regulates food intake, and also an energy homeostasis system that regulates activity and thermogenesis, and that these systems are coupled. The brain is the coordinating organ of metabolic activity. And the brain’s food reward and energy homeostasis systems are altered in obesity.

But the direction of causality is unclear. Is “reducing food reward” the best strategy against obesity, or is “maximizing food reward with nourishing food” the best strategy?

Some data may illustrate what I mean. Here’s an investigation of how the food reward system in rats controls appetite to regulate protein and carbohydrate consumption. The data is from multiple studies and was collected by Simpson and Raubenheimer [2].

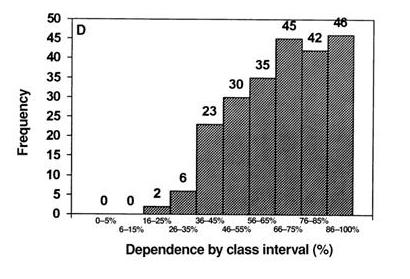

Rats were given a chow consisting of protein and carbohydrate in varying proportions. The figure below shows how much of the protein-carb chow they ate.

I’ve drawn a kinked blue line to show what a “Perfect Health Diet” analysis would consider optimal. Protein needs consist of a fixed amount of protein, around 70 kJ, to meet structural needs, plus enough protein to make up any dietary glucose deficiency via gluconeogenesis. Glucose is preferable to protein as a fuel. Glucose needs in rats are in the vicinity of 180 kJ. When dietary glucose intake falls short of 180 kJ, rats eat extra protein; they seek to make carb+protein intake equal to 250 kJ so they can meet both their protein and carb needs, with gluconeogenesis translating the dietary protein supply into the body’s glucose utilization as necessary.

As the data shows, the food reward system in rats seems to organize food intake to precisely match this:

- When the chow is low-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until carb+protein intake is precisely 250 kJ – then they stop eating.

- When the chow is high-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until protein intake is precisely 70 kJ – then they stop eating.

I interpret this to show that the food reward system evolved to optimize our health, and in healthy animals does an excellent job of getting us to eat in a way that achieves optimal health.

Note that if the chow is high-carb, rats eat more total calories. Is this because their diet has “high food reward”? No, it is because it is malnourishing. It is protein deficient.

Now, a diet of wheat, sugar, and omega-6 fats is malnourishing. There are any number of nutrients it is deficient in. So the food reward system ought to persuade people to eat more until they have obtained a sufficiency of all important nutrients, and rely on the energy homestasis system to dispose of the excess calories in one way or another. But if the energy homeostasis system fails to achieve this, then obesity may be the result.

If this picture is correct, then what is the solution to obesity? Is it to eat a diet that is bland and low in food reward? I don’t think so; the food reward system evolved to optimize our health. Rather the diet that defeats obesity will be one that is efficiently nourishing and maximally satisfies the food reward system at the minimum possible caloric intake.

A good test of these two strategies is the severely calorie (and nutrient) restricted diet. It would be hard to conceive of a diet lower in food reward than one with no food at all. Yet severe calorie restriction produces temporary weight loss followed by regain – often to even higher weights. This “yo-yo dieting” cycle may be repeated many times. I think this proves that at least some methods of “reducing food reward” – the malnourishing ones – are obesity-inducing.

So I would phrase the goal of an anti-obesity diet as achieving satisfaction of the food reward system, rather than as reducing food reward; and would say that wheat, sugar, and seed oils are obesogenic because they fail to provide genuine food reward, and thus compel the acquisition of additional calories.

Conclusion

Jimmy Moore is friends with the smartest people in the low-carb movement, so this discussion is sure to be interesting. I’m grateful that he’s persuaded people to comment on Shou-Ching’s and my ideas, and I’m eager to hear what Jimmy’s experts have to say.

One thing I’m sure of, the discussion will help us understand the many open issues in low-carb science. It should be a lot of fun!

References

[1] Cordain L et al. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92. http://pmid.us/10702160.

[2] Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005 May;6(2):133-42. http://pmid.us/15836464.

Recent Comments