This started as a note for an Around the Web, but has grown … so it will stand on its own.

The Red Meat Study

The Paleosphere has been abuzz about the red meat study from the Harvard School of Public Health. I don’t have much to say about it because the claimed effect is small and, at first glance, not enough data was presented to critique their analysis. There are plenty of confounding issues: (1) We know pork has problems that beef and lamb do not (see The Trouble With Pork, Part 3: Pathogens and earlier posts in that series), but all three meats were lumped together in a “red meat” category. (2) As Chris Masterjohn has pointed out, the data consisted of food frequency questionnaires given to health professionals, and most respondents understated their red meat consumption. Those who reported high meat consumption were “rebels” who smoked, drank, and did not exercise. (3) The analysis included multivariate adjustment for many factors, which can have large effects on assessed risk. Study authors can easily bias the results substantially in whatever direction they prefer. I’ve discussed that problem in The Case of the Killer Vitamins.

So it’s hard to judge the merits of the red meat study. However, another study from HSPH researchers came out at the same time that was outright misleading.

The White Rice and Diabetes Study

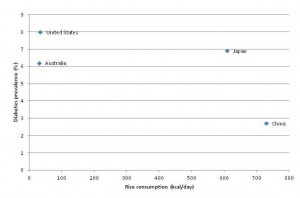

This study re-analyzed four studies from four countries – China, Japan, Australia, and the United States – to see how the incidence of diabetes diagnosis related to white rice consumption within each country.

Here was the main data:

The key thing to notice is that the y-axis of this plot is NOT incidence of type 2 diabetes. It is relative risk within each country for type 2 diabetes.

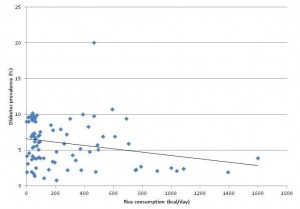

I looked up diabetes incidence and rice consumption in these four countries. Here is the scatter plot:

Here is the complete FAO database of 86 countries, with a linear fit to the data:

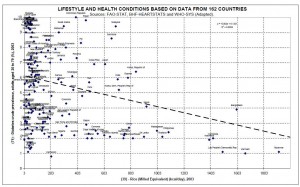

UPDATE: O Primitivo has data for 162 countries and a better chart. Here it is – click to enlarge:

If anything, diabetes incidence goes down as rice consumption increases. Countries with the highest white rice consumption, such as Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Bangladesh, have very low rates of diabetes. The outlier with 20% diabetes prevalence is the United Arab Emirates.

A plausible story is this:

- Something entirely unrelated to white rice causes metabolic syndrome. Possibly, the something which causes metabolic syndrome is dietary and is displaced from the diet by rice consumption, thus countries with higher rice consumption have lower incidence of metabolic syndrome.

- Diabetes is diagnosed as a fasting glucose that exceeds a fixed threshold of 126 mg/dl. In those with impaired glucose regulation from metabolic syndrome, higher carb intakes will tend to lead to higher levels of fasting blood glucose. (Note: this is true for carb intakes above about 40% of energy. On low-carb diets, higher carb intakes tend to lead to lower fasting blood glucose due to increased insulin sensitivity. However, nearly everyone in these countries eats more than 40% carb.) Thus, of two people with identical health, the one eating more carbs will show higher average blood glucose levels.

- Therefore, the fraction of those diagnosed as diabetic (as opposed to pre-diabetic) will increase as their carb consumption increases.

- In China and Japan, but not in the US and Australia, white rice consumption is a marker of carb consumption. So the fraction of those with metabolic syndrome diagnosed as diabetic will increase with white rice consumption in China and Japan, but will be uncorrelated with white rice consumption in the US and Australia.

Thus, diabetes incidence may be lower in China and Japan (due to lower incidence of metabolic syndrome on Asian diets), but higher among Chinese and Japanese eating the most rice (due to higher rates of diagnosis on the blood sugar criterion). This explains all of the data and is biologically sound.

What did the HSPH researchers conclude?

Higher consumption of white rice is associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes, especially in Asian (Chinese and Japanese) populations.

No: Internationally, higher consumption of white rice is associated with a significantly reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, and the Chinese and Japanese experience is consistent with that. Carb consumption is associated with a higher rate of diabetes diagnosis within populations at otherwise similar risk for diabetes. White rice consumption is correlated to carb consumption especially strongly in Asian (Chinese and Japanese) populations.

Food Reward and “Eat Less, Move More” in Diabetes

Of course, the study authors knew that diabetes incidence is lower in countries that eat more white rice. How do they reconcile this with their claim that white rice increases diabetes risk?

The recent transition in nutrition characterised by dramatically decreased physical activity levels and much improved security and variety of food has led to increased prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance in Asian countries. Although rice has been a staple food in Asian populations for thousands of years, this transition may render Asian populations more susceptible to the adverse effects of high intakes of white rice …

In other words, rice-eating countries have higher physical activity and more boring food – just look at the notoriously tasteless cuisines of Thailand, China, and Japan – and their inability to eat high quantities of food has hitherto protected Thais, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, and Indonesians from diabetes.

However, once those rice eaters become office workers and learn how to spice their rice with more varied flavors, the deadly nature of rice may be revealed.

Stephan Guyenet writes that “Food Reward [is] Approaching a Scientific Consensus.” It certainly seems so; it is emerging as a catch-all explanation for everything, a perspective that can be trotted out in a few concluding sentences to reconcile a hypothesis (white rice causes diabetes) with data that contradict it.

Conclusion

To me, the HSPH white rice study doesn’t look like science. It looks like gaming of the grant process – generating surprising and disturbing results that seem to warrant further study, even if the researchers themselves know the results are most likely false.

Consensus or no – and consensus in science isn’t necessarily a sign of truth (hat tip: FrankG) – the food reward perspective seems to me an incomplete explanation for what is going on. It puts a lot of weight on a transition from highly palatable (Thai, Japanese, Chinese) food to “hyperpalatable” (American, junk) food as an explanation for obesity and diabetes. It seems to me that the lack of nutrients and abundance of toxins in the junk food may be just as important as its “hyperpalatability.” It’s the inability of the junk food to satisfy that is the problem, not its palatability.

I’m glad that the food reward perspective may start being tested against Asian experiences. That may shed a lot of light on these issues.

Recent Comments