Last week in An Anti-Cancer Diet (Sep 28, 2011), I recommended that cancer patients eat 400 to 600 carb calories per day, but combine it with a program of daily intermittent fasting plus longer “ketogenic fasts” and periods of ketogenic dieting or low-protein dieting to promote autophagy.

The recommendation to eat some carbohydrates, plus my statement that it was possible for cancer patients to develop a “glucose deficiency” which might promote metastasis and the cancer phenotype, seems to have stirred a bit of a fuss.

In addition to making @zooko sad, it led Jimmy Moore to reach out to a number of gurus to ask their opinion. On Twitter, Jimmy says:

Working on an epic blog post today about @pauljaminet and his “safe starches” concept. Input from numerous #Paleo and #lowcarb peeps.

I’m excited to have this discussion. As Jimmy later tweeted:

Should be fun to hash all this out publicly for ALL of us to understand better about your concepts. Here’s to education.

So far, I have seen responses from Dr. Kurt Harris and Dr. Ron Rosedale. On PaleoHacks, there is an extensive discussion on a thread started by Meredith.

UPDATE: Jimmy’s post is up: Is There Any Such Thing as “Safe Starches” on a Low-Carb Diet?.

I think this discussion is wonderful. With so many people putting effort into this, I have an obligation to respond. I’ll start with Kurt’s perspective today, then Ron Rosedale’s early next week, then whoever else participates in Jimmy’s epic post.

PHD and Archevore: Similar Diets

Kurt and I have essentially identical dietary prescriptions. However, our reasoning sometimes works from different premises. Kurt observes:

My arguments are based more on ethnography and anthropology than some of Paul’s theorizing, but I arrive at pretty much the same place that he does.

An example of a point of agreement is Kurt’s endorsement of glucose-based carbs:

[I] see the human metabolism as a multi-fuel stove, equally capable of burning either glucose or fatty acids at the cellular level depending on the organ, the task and the diet, and equally capable of depending on either animal fats or starches from plants as our dietary fuel source …

We are a highly adaptable species. It is not plausible that carbohydrates as a class of macronutrient are toxic.

I think that if there is no urgency about generating ATP then fatty acid oxidation is slightly preferable to glucose burning. But essentially, I share Kurt’s point of view. Our ancestors must have been well adapted to consuming high-carb diets, and necessity surely thrust such diets upon some of our ancestors. Certainly there’s no reason why consuming starch per se should be toxic.

Kurt and I also agree on which starches are safe:

These starchy plant organs or vegetables are like night and day compared to most cereal grains, particularly wheat. One can eat more than half of calories from these safe starches without the risk of disease from phytates and mineral deficiencies one would have from relying on grains.

White rice is kind of a special case. It lacks the nutrients of root vegetables and starchy fruits like plantain and banana, but is good in reasonable quantities as it is a very benign grain that is easy to digest and gluten free.

We agree that safe starches are a more useful part of the diet than fruits and vegetables:

[E]ating starchy plants is more important for nutrition than eating colorful leafy greens …

I view most non-starchy fruit with indifference. In reasonable quantities it is fine but it won’t save your life either. I like citrus now and then myself, especially grapefruit. But better to rely on starchy vegetables for carbohydrate intake than fruit.

We agree on the optimal amount of carbs to eat:

I personally eat around 30% carbohydrate now and have not gained an ounce from when I ate 10-15% (and I have eaten as high as 40% for over a year also with zero fat gain) If anything I think even wider ranges of carbohydrate intake are healthy.

One can probably eat well over 50% of calories from starchy plant organs as long as the animal foods you eat are of high quality and micronutrient content.

I think being slightly low-carb, in the sense of eating slightly below the glucose share of energy utilization which I estimate at about 30% of energy, is optimal. However, I think we are metabolically flexible enough that a very broad range of carb intake may be nearly as good. I would consider 10% a minimal but healthy intake of carbs, and 50% a higher-than-optimal, but still healthy, intake so long as the carbs are “safe” and the diet is nourishing.

Differing Origins of Our Ideas

Kurt mentions that his ideas are more derived from ethnography and anthropology than mine.

I give great weight to evolutionary selection as an indicator of the optimal diet, and am friendly to ethnographic and anthropological arguments. If I don’t give tremendous weight to such arguments, it’s because I think some other lines of argument give us finer evidence about the optimal diet.

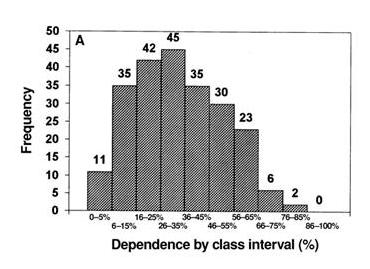

Here, from a paper by Loren Cordain et al [1], are representations of hunter-gatherer diets:

The top graph shows plant food consumption by calories, the bottom graph animal+fish consumption by calories. The numbers are how many of 229 hunter-gatherer societies ate in that range. Typically, hunter-gatherers got 30% of calories from plant foods and 70% of calories from animal foods.

I think the Cordain et al data supports my argument that obtaining 20% to 30% of calories from carbs is probably optimal. However, it’s hardly decisive. There is considerable variability, mainly in response to food availability in the local environment. Inuits, who had few edible plants available, ate hardly any plant foods; tropical tribes with ready access to starchy plants, fruits, and fatty nuts sometimes obtained a majority of calories from plants.

Hunter-gatherer diets, therefore, are a compromise between the diet that is healthy and the diet that is easy to obtain. A skeptic could argue that hunter-gatherers routinely ate a flawed diet because some type of food was routinely easier to obtain than others, and thus systematically biased the diet.

I believe evidence from breast milk is both more precise about what diet is optimal, and much harder for skeptics to refute. Breast milk composition is nearly the same in all humans worldwide, and it has been definitely selected to provide optimal nutrition to infants.

So breast milk, I think, gives us a much clearer indication of the optimal human diet than hunter-gatherer diets. It is an evolutionary indicator of the optimal diet, but it is not ethnographic or anthropological.

There are other evolutionary indicators of the optimal diet — mammalian diets, for instance, and the evolutionary imperative to function well during a famine — which, as readers of our book, we also use to determine the Perfect Health Diet. So, while I think ethnographic and anthropological findings give us important clues to the optimal diet, I think there are plenty of other sources of evidence to which we should give weight. Fortunately, all of these sources of insight seem to be consistent in supporting low-carb animal-food-rich diets — a result which is gratifying and should give us confidence.

Food Reward and Obesity

Kurt seems to have been more persuaded than I am by Stephan Guyenet’s food reward hypothesis (which is, of course, not of Stephan’s creation – it is the dominant perspective in the community of academic obesity researchers). Kurt writes:

Low carb plans have helped people lose fat by reducing food reward from white flour and excess sugar and maybe linoleic acid. This is by accident as it happens that most of the “carbs” in our diet are coming in the form of manufactured and processed items that are simply not real food. Low carb does not work for most people via effects on blood sugar or insulin “locking away” fat. Insulin is necessary to store fat, but is not the main hormone regulating fat storage. That would be leptin.

I agree with Kurt in rejecting what he calls the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, but I am uneasy at the confident assertion that “reducing food reward” is the mechanism by which excluding flour, sugar, and omega-6 fats helps people lose weight.

Let me say first that there is no doubt that the brain has a food reward system that regulates food intake, and also an energy homeostasis system that regulates activity and thermogenesis, and that these systems are coupled. The brain is the coordinating organ of metabolic activity. And the brain’s food reward and energy homeostasis systems are altered in obesity.

But the direction of causality is unclear. Is “reducing food reward” the best strategy against obesity, or is “maximizing food reward with nourishing food” the best strategy?

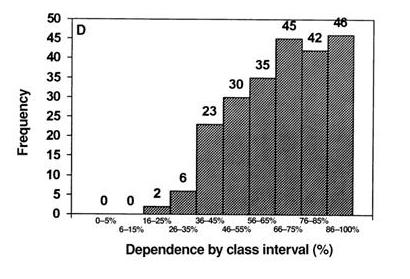

Some data may illustrate what I mean. Here’s an investigation of how the food reward system in rats controls appetite to regulate protein and carbohydrate consumption. The data is from multiple studies and was collected by Simpson and Raubenheimer [2].

Rats were given a chow consisting of protein and carbohydrate in varying proportions. The figure below shows how much of the protein-carb chow they ate.

I’ve drawn a kinked blue line to show what a “Perfect Health Diet” analysis would consider optimal. Protein needs consist of a fixed amount of protein, around 70 kJ, to meet structural needs, plus enough protein to make up any dietary glucose deficiency via gluconeogenesis. Glucose is preferable to protein as a fuel. Glucose needs in rats are in the vicinity of 180 kJ. When dietary glucose intake falls short of 180 kJ, rats eat extra protein; they seek to make carb+protein intake equal to 250 kJ so they can meet both their protein and carb needs, with gluconeogenesis translating the dietary protein supply into the body’s glucose utilization as necessary.

As the data shows, the food reward system in rats seems to organize food intake to precisely match this:

- When the chow is low-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until carb+protein intake is precisely 250 kJ – then they stop eating.

- When the chow is high-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until protein intake is precisely 70 kJ – then they stop eating.

I interpret this to show that the food reward system evolved to optimize our health, and in healthy animals does an excellent job of getting us to eat in a way that achieves optimal health.

Note that if the chow is high-carb, rats eat more total calories. Is this because their diet has “high food reward”? No, it is because it is malnourishing. It is protein deficient.

Now, a diet of wheat, sugar, and omega-6 fats is malnourishing. There are any number of nutrients it is deficient in. So the food reward system ought to persuade people to eat more until they have obtained a sufficiency of all important nutrients, and rely on the energy homestasis system to dispose of the excess calories in one way or another. But if the energy homeostasis system fails to achieve this, then obesity may be the result.

If this picture is correct, then what is the solution to obesity? Is it to eat a diet that is bland and low in food reward? I don’t think so; the food reward system evolved to optimize our health. Rather the diet that defeats obesity will be one that is efficiently nourishing and maximally satisfies the food reward system at the minimum possible caloric intake.

A good test of these two strategies is the severely calorie (and nutrient) restricted diet. It would be hard to conceive of a diet lower in food reward than one with no food at all. Yet severe calorie restriction produces temporary weight loss followed by regain – often to even higher weights. This “yo-yo dieting” cycle may be repeated many times. I think this proves that at least some methods of “reducing food reward” – the malnourishing ones – are obesity-inducing.

So I would phrase the goal of an anti-obesity diet as achieving satisfaction of the food reward system, rather than as reducing food reward; and would say that wheat, sugar, and seed oils are obesogenic because they fail to provide genuine food reward, and thus compel the acquisition of additional calories.

Conclusion

Jimmy Moore is friends with the smartest people in the low-carb movement, so this discussion is sure to be interesting. I’m grateful that he’s persuaded people to comment on Shou-Ching’s and my ideas, and I’m eager to hear what Jimmy’s experts have to say.

One thing I’m sure of, the discussion will help us understand the many open issues in low-carb science. It should be a lot of fun!

References

[1] Cordain L et al. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92. http://pmid.us/10702160.

[2] Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005 May;6(2):133-42. http://pmid.us/15836464.

Thanks, Paul, for such a generous and thoughtful response and elaboration. Have you already responded to this study:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/09/110919073845.htm

It seems to be in line with your hypotheses.

Hi aek,

I mentioned it on Saturday’s Around the Web, but haven’t had time to study it.

I keep seeing references to intermittent fasting in topic after topic, this being yet another. Is there a single best book or post on everything about it, that consolidates what is know in one place? Why IF, When to IF, How to IF, What to expect it to do?

Always a skeptic, and mainly just not wanting to agree with you ALL OF THE TIME (it’s hard not to), I don’t think that we can extrapolate what an infant needs or can handle nutritionally to what an adult needs. How many differences between an infant and an adult are there? What is an infant’s ability to digest protein, and what is an adult’s capacity to synthesize various molecules in the body compared with an infant’s? Isn’t a child growing whereas an adult is not, can this mean a difference in requirement for any macronutrients?

Your view on food reward systems is very interesting. A great example of thinking outside the box. I’m still of the persuasion that when there is a problem with over-consumption, whatever that means, it is a dysregulation problem, like anxiety for example, but you have added a new and interesting aspect of it that makes sense on an intuitive level.

Hi Eric,

I think that’s a book that’s still waiting to be written. I might get to it in 3-4 years.

Hi Stabby,

Thanks! I agree, one must extrapolate from an infant’s needs to estimate an adult’s. The key difference is that the brain consumes 50% of energy in an infant but 20% in adults; there are other less important differences. So breast milk doesn’t tell us precisely what an adult should eat. But it gives a clue.

I’m going to be fleshing out my ideas on obesity in coming posts, once I get past this conversation with Jimmy’s experts.

Thanks! I am looking forward to hearing more of what you have to say on this topic.

I’m glad you’re doing this. Given recently discovered melanoma in the family, I’m particularly sensitive to the hardline “GLUCOSE FEEDS CANCER RUN RUN RUN” arguments… especially since I’ve gotten the family over the hump thanks to safe starch!

Could be just what I fixated on, but that (cancer, e.g. Kruse and Diamond) and the post-SAD diabetic epidemic seemed to be the two major critical counters. I look forward to your responses — although that seems to be a lot of work!

Thanks for your helpful post on this big picture issue. I particularly like your reference to breast milk. Our 5th child will be here soon. It’s amazing and discouraging to hear the bad rap medical folks have on saturated fat -despite best milk! WIC program did are high in sugar, flour and getting lower on fat. However, we continue to live by example and share what we know helps kids grow.

Keep up the good work

Paul,

I find that discussion on safe starches amazing. Not by bringing up scientific discussion, but for some gems in the responses. You know that I dont agree with you on the “glucose deficiency” issue. There is no science to back it up, as I showed on my posts on the subject (http://www.lucastafur.com/search/label/ketomyths).

When somebody wants to know how to eat, I first recommend your diet. I agree with the overall recommendations. Whether you prefer more or less carbs is the least important issue. The most important aspect for me is reducing grains, sugar and excessive linoleic acid. Obviously, in some circunstances, a ketogenic diet will always be superior. And by ketogenic I mean <20g carbohydrates per day.

Anyways, back to the discussion on your safe starches. I find the following comments really amazing (in a bad sense):

Colette Heimowitz: "This is also the first time I have ever heard that glycation can be good for you."

Dana Carpender: "I am not particularly excited about the whole “production of mucus in the digestive tract” thing. (…) This does not mean that deliberately irritating the gut is a good idea."

This shows why many low carb dogmas are weak. Lack of basic understanding of molecular biology and physiology.

Hi Paul,

Just found your site and am fascinated and so grateful for all your work.

I’ve been on an anti-candida diet for 15 months and, while I have resolved many symptoms, I still am not ‘healthy.’ I have multiple food allergies, hypothyroidism, lots of immune reactions to environmental toxins (multiple chemical sensitivity), not the energy I think I should have, etc, etc.

I’m really considering adding some more starches to my diet after reading your website. At this point on the anti-candida diet, I am zero carb. I mainly eat meats, fats, and a few veggies along with some fermented foods like yogurt and cultured butter.

I did try eating some starchy veggies in the past like carrots and winter squash and even a few low sugar fruits, but I always felt like some candida symptoms were returning – bloating with meals, inner ear itching, anal itching, dizziness, hypoglycemia. Do you think this is a true return of candida or just my body needing time to readjust to digesting carbs?

I had a stool test done by Great Plains Laboratory and no harmful pathogens showed up, but I did have a lack of good bacteria. Not sure what to make of that . . . don’t even know if it would be all that accurate since I’m dealing with chronic constipation and had to do an enema to get the sample.

So, I guess I’m curious what you think about the return of what I thought were candida symptoms when adding carbs. Thanks for any input!

Hi Lucas,

Thanks, I’m glad to hear you recommend our diet.

We’ll have to disagree about whether it’s possible to have a glucose deficiency. Also, though I am fond of ketosis, you don’t need to severely restrict carbs to achieve ketosis, and I don’t believe it’s necessary or desirable to keep carbs below 20 g to be in a healthy ketogenic diet.

I’m glad to see you’re broadening your scope on the blog, you have a lot of interesting things to say.

A number of commenters in Jimmy’s post were weak in terms of science. Jimmy should have invited you!

Best, Paul

Steven’s theory is particularly convincing for somebody born and raised in America because it explains the appeal of the fast-food . Even Dr.Kurt G.Harris thinks that majority of fattening foods come in a box.Yes , here, but not everywhere in the world.

I would never be able to loose weight and not to regained it if I followed Steven’s advice.Weight loss is not the main benefit. Very early in my diet I got relieve from numerous health issues, that can not be attributed to a weight loss.During summer I manage to convince my mother(she lives in Russia) to remove from her breakfast foods like oatmeal and high quality very natural bread(she used to have sandwiches for her breakfast), at the same time she started to eat more eggs, cheese, butter, cold cuts. Result – satiety for several hours. Before she was hungry in 2 hours. The same story with her dinner when bread and starches were removed. By the way, I didn’t try to prepare my 75 yo mother for a Miss Universe contest. I was worried about her blood pressure and she has been suffering from extraesophageal reflux disease for more than 10 years. Blood pressure dropped to normal, amount of mucus in her throat significantly decreased.Sure, she lost 23 lb, but carb restriction gave her much more than just a weight loss.

To Eric:

I found the website http://gettingstronger.org/2010/11/learning-to-fast/ to be particularly inspiring and helpful. I wouldn’t be able to start IF before practicing LC first – used to be hungry all the time.

Paul, I thought you might be interested in this. I think it demonstrates a possible mechanism how microbes cause metabolic syndrome, and also how they can influence food reward.

In ob/ob mice, blocking or enhancing CB1 can cause an 88% decrease or 100% increase in plasma LPS, respectively, likely via modulation of gut barrier function. CB1 expression in mice can be decreased -25% by prebiotics, -60% by antibiotics, and increased 160% by a ‘high fat’ lab diet (but only by 60% if the HFD includes prebiotics) 191). Altering mice gut microbiotas via prebiotics and probiotics can significantly modulate intestinal permeability 192) 193).

CB1 receptor knockout mice: protected from diet-induced obesity, despite similar caloric intakes as mice who do become obese 194) 195).

CB1 blocker in diet-induced obese mice: -50% reduction in adiposity, correction of insulin resistance and lowered plasma leptin levels 196) 197).

CB1 blocker in obese monkeys: -23% reduction in food intake, bodyfat by -39%, leptin by -34% (pair fed animals did not experience improvements) 198).

CB1 blocker in humans: 4.7 kg greater weight loss over 1 year, compared to placebo 199).

The CB1 receptor can significantly modulate drug and palatable food seeking behavior in mice 200) 201) 202), including sugar 203) 204), chocolate 205), ’emotional behavior’ 206), anxiety, stress and depressive-like behavior 207). CB1 blocking reduces reward seeking in rats 208) 209). CB1 receptors are densely expressed in neurons expressing dopamine D1 receptors 210).

Continuously injecting lipopolysaccharid (LPS) into mice, at levels that mimic the endotoxemia seen in metabolic-syndrome mice, causes glucose levels, insulin levels, and weight gain similar to ‘high-fat’ fed mice 211). Continuous LPS can cause insulin resistance in cats 212). A single LPS injection can cause a 100% increase in serum leptin levels and 44% increase in triglycerides 213). Continuously injecting humans with endotoxin can cause a 35% decline in insulin sensitivity, and increases adipose tissue inflammation 214) 215). Inflammation within adipose tissue occurs during obesity 216), and interrupting this inflammation prevents metabolic abnormalities 217).

“In conclusion…we found that metabolic concentrations of plasma LPS are a sufficient molecular mechanism for triggering the high-fat diet–induced metabolic diseases obesity/diabetes.” 218)

Sources @ http://flare8.net/health/doku.php/diseases#microbes1

Hi Jean,

Zero carb is not desirable if you do, in fact, have a Candida infection. Zero-carb impairs immunity and ketosis promotes systemic invasion of the Candida. Anti-fungal resistance is much better with some dietary starches.

The symptoms you get upon eating carbs are generalized signs of immune activity. They probably indicate a leaky gut, allowing toxin entry to the body that the immune system has to deal with. I think the zero-carb diet may contribute to that.

I would try eating easily digestible glucose-based carbs, like rice syrup, for a while. This should help your body recover while minimizing the activity of gut bacteria. Then gradually mix in more plant foods.

I’m not familiar with the Great Plains stool test. Would it have detected Candida?

Hi flare,

I think I saw you make a very similar comment on another blog (Stephan’s?), and thought it was fascinating.

If differing LPS levels are behind the experimental results in rodents, we really have to understand the mechanisms regulating LPS entry. They might not be the same in rodents and humans; and LPS might not have similar effects.

The role of the endocannibinoid receptor is very interesting.

Thanks for contributing!

Low-carb dogma is pretty funny.

According to Dr. Kruse (the scatter-brained, semi-coherent brain surgeon that is “re-engineering humans” by flipping their “epigenetic switches”) both you and Dr. Harris are recommending “madness.”

And Cordain takes you to task for ignoring glycemic index and glycemic load.

And Jimmy polled the “experts”, and then threw in anonymous people and random blog readers.

And a lot more funny shit. Low-carb dogma is pretty funny.

Hi Paul

Thanks for the kind mention and the traffic.

I think our readers should be reassured by the convergence or coincidence in the substance of our recommendations because they do arise from different approaches.

It is worth emphasizing that my core concept of the EM2 (evolutionary metabolic milieu) is what drives my theorizing. The EM2 I see as a set of operating parameters that would have evolved to allow us to achieve the fantastic biological success across radically varying biomes that we do. So this core idea is what allows the diet itself to evolve as I have gathered empirical clinical experience and done more reading in both historical disciplines and contemporary medical science.

One conceit I am loathe to part with is to keep the parameters of the EM2 as wide as they can be, but no wider. I am inclined to imagine that an optimal diet characterized by tightly defined macronutrient ratios, magic special plants (I know you agree with me on magic plants : ) ) or even obligate fish consumption would have been modified or selected against over the tens of millennia we have been spreading around the world. Ancient people must have been able to eat without having a clue what a macronutrient was, and I am repelled by the idea that there is an “accidental optimum” of carbohydrate or fat intake. Minimums, yes.

But one important difference is that I do eat 20-30% carbs, but I don’t necessarily agree that eating much larger fractions of carbohydrate is any worse. I am truly neutral in the 20- 60% range if there is adequate protein.( Of course, the carbs can’t be mineral binding or amino acid deficient cereal grains. No soaking or sprouting, folks)

And my paleoanthro evidence is not based on Cordain’s quantitative guesses, which to me seem a bit like trying to suss out opinions on football by averaging the opinions of packers fans with those who favor the bears. It is more based on the health of those living in the modal extremes, that tend to be biased either towards starch or animal fat, depending on biome or season, but not usually some average of both. We observe that thriving and longevity are possible at the extremes as long as there is quality animal food in the mix and not grains for the carbs.

“I agree with Kurt in rejecting what he calls the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, but I am uneasy at the confident assertion that “reducing food reward” is the mechanism by which excluding flour, sugar, and omega-6 fats helps people lose weight.

Context. I am responding to Jimmy and writing with his audience in mind, trying to disabuse them of the notion that a potato is the same as coca cola.

Be assured, my three original NADs are still in the legion of putative bad guys as far as atherosclerosis, cancer and inflammation. Whether the fat loss effects are due their NAD properties is less clear to me. And I did not say that FR effects were the sole factor, just one.

I’ll comment more on FR in a separate box…

Paul:

I think there are several problems with FRH as stated, and you touch on a major one, with which I’m in full agreement: reward alone cannot explain observed behavior. I’ve previously expanded on this topic at length in Why Snack Food Is Addictive, and I’m in the process of exploring the entire suite of hunger motivations in the epic series “Why Are We Hungry?”

However, while I largely agree with the basic PHD recommendations, I’m still not sure that carbohydrate consumption over our bodies’ needs is OK for everyone. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pre-obese, formerly obese, and obese-but-still-gaining-weight exists and is empirically measurable via lack of metabolic flexibility – and though we’re still trying to puzzle out its nature, effects, and etiology, I’m not yet ready to advocate higher carb intakes for people who have a demonstrable problem disposing of them.

Someone with impaired metabolic flexibility is most definitely NOT a “multi-fuel stove”.

JS

I see I can’t edit after posting…

I wanted to add that we do agree on the optimal method of fasting. 8 hour eating window or 36 hour fasts with lower frequency.

And your logic and math on glucose requirements and the desirability of eating it rather than making it from protein ( absent brain disease or cancer) is 100% concordant with mine. So 20% should be the lower limit for most people unless it is a special situation.

I was, coincidentally, reading PHD for the first time this morning and it does strike me that your readers may think that your writings might be derived from mine or vice versa, but as I say I am only now reading your book.

I think the convergence in our conclusions should be nothing but reassuring to our readers and it bears emphasizing that they were independently arrived.

The concordant indictment of what I call the NADs in particular feels very confirmatory to me…

JS – isocaloric diets in metabolic wards doe seem to suggest that most people have a “multi-fuel stove”.

Hi CPM,

Some of those responses were surprisingly thoughtless. You could accuse Kurt and I of a lot of things, but saying “science be damned” isn’t one of them.

I couldn’t follow Cordain’s reasoning at all. Lots of people are aware of the concepts of glycemic load and glycemic index, and yet eat rice and potatoes.

Hi Kurt,

Welcome, and yes I do think it’s reassuring that many different lines of argument converge to similar conclusions.

I will be the first to agree, and I’ve done this in regard to Stephan, that there is essentially no direct evidence that low-carb diets are superior to moderate-carb diets in healthy people. The main evidence, from my point of view, is evolutionary: breast milk composition is always fat rich, and all mammals that carb-dominant diets transform their dietary carbs to other macronutrients. Evolution didn’t have to give them the “expensive guts” to do this transformation, unless it was advantageous.

Science will be a long time catching up to these evolutionary arguments, I think, in terms of giving us solid guidance about diet.

Thanks for the clarification re flour, sugar, and omega-6. My discussion of food reward was not intended to rebut you, it was just some ideas I’ve been meaning to put forward and this seemed a good time.

Hi JS,

Thanks much for your great series. It is going to be cited for a long time.

Definitely people with metabolic dysfunction can have trouble with carbs. However, they may have some trouble with all diets. It is a tricky problem finding the optimum, and the optimum may differ among people. Low carb diets are very helpful for diabetics and many obese, but it’s still a puzzle understanding all the ways disease can interact with diets.

I think a lot of the people in Jimmy’s panel were very focused on diets for the obese or diabetic, and looked at our diet through that lens. I’m not sure they’re aware that we do recommend lower carb consumption in some diseases.

“Let me say first that there is no doubt that the brain has a food reward system that regulates food intake, and also an energy homeostasis system that regulates activity and thermogenesis, and that these systems are coupled. The brain is the coordinating organ of metabolic activity. And the brain’s food reward and energy homeostasis systems are altered in obesity.”

“Is “reducing food reward” the best strategy against obesity, or is “maximizing food reward with nourishing food” the best strategy?

This second quote is, I think, not using the definition of food reward that Stephan is using in his recent series. To maximize foo shouled reward with nourishing food does not really make sense. Food reward as Stephan is using the term is simply the ability of the food to reinforce its own consumption. It is not the same as palatability nor is it true that making food more nourishing would necessarily enhance it.

“If this picture is correct, then what is the solution to obesity? Is it to eat a diet that is bland and low in food reward? I don’t think so; the food reward system evolved to optimize our health. ”

Per my previous comment, low FR does not necessarily mean a bland diet, even if in general “blandifying” a given food lowers FR. I agree that the food reward system evolved. But why is it implausible that unnatural engineered foods might be able so subvert this system via reward pathways that are otherwise normal. Drugs designed by man exploit our physiology, why cannot foods that are not found in nature do the same whether by accident or design? Yes, this could be due to “toxic” effects from NADS, but would not have to be.

Witness paleo lemon bars or paleo apple pie or paleo ice cream or paleo whatever.

I believe one can create high FR foods that are actually highly nutritious, and these may be over-consumed with no toxicity or deficiency whatsoever. I believe this because I see people do it, and I’ve done it myself as an experiment.

I know people who eat 100% healthy PHD type whole foods paleo diets for 70% percent of their calories, and presumably are replete with all nutrients. Unfortunately, they still like beer and cake and cookies and that makes up the other 30% and they are still fat. So I am skeptical of the idea that overconsumption of high FR foods is only driven by being malnourished.

“Our ancestors must have been well adapted to consuming high-carb diets, and necessity surely thrust such diets upon some of our ancestors. Certainly there’s no reason why consuming starch per se should be toxic.”

I would playfully turn this on its head and say we evolved to be able to get calories from the fat stores of large bodied animals in environments where starchy vegetables and fruit is scarce.

“I believe evidence from breast milk is both more precise about what diet is optimal, and much harder for skeptics to refute. Breast milk composition is nearly the same in all humans worldwide, and it has been definitely selected to provide optimal nutrition to infants.”

I totally like the breast milk argument for refuting the idea that fat is toxic, but not so much for determining the “optimal” macro ratios for fully grown adults. Plus, if you try this argument with bovines who end up eating nothing but grass, funny things happen…

“like totally like” should read “totally like…”

hit post too soon, cannot edit ….

wow i agree completely with both paul and kurt. that being said, J Stanton has written several posts on this subject as well. i believe he probably has a middle ground between the two here. he tends to lean(per my understanding anyway) towards the combination of food reward as satiety and satiation, incentive salience, and palatability. i’m sure you know of all this, i just wanted to point out that leaning one way or the other on this issue of “what makes us fat” is foolish. not that i really see much of that outside people that write books (wheat belly, cough!) i prefer JS’s stance on the issue. if we eat crap foods, the total lack of nutrients will drive us to consume more(incentive salience). if we eat more nutritious foods, we will naturally eat less as the body is pretty good(in metabolically “normal” people) at determining satiation(oversimplification but it has kept me on track for a while now). it would seem from all the differing viewpoints that this “food reward” concept is completely relative to whatever pathways are activated. if we had high palatability foods that were nutritious, i dont think there would be much issue here. but again, relative. i happen to think that a steak is much more palatable than a box of milk duds. apparently my body agrees. very complex issue though and there are some of the most brilliant people i’ve read working on this daily. (you guys) much much smarter than myself.

Hi Kurt,

Great points and taking us a bit farther than I wish to go in a comment thread. But briefly:

I think a healthy person eating nourishing food experiences nothing that “reinforces its own consumption.” As more of a given nutrient is consumed, the desire to consume the same thing again decreases.

So I think Stephan’s definition of food reward is already divorcing the food reward system from its evolutionary function and assuming the existence of either (a) pathological foods which fool the evolutionary food reward system or (b) a damaged food reward system which improperly rewards self-damaging behavior. I don’t like his definition because it doesn’t assign any reward value to beneficial foods which are handled normally.

I’m willing to create my own definitions when I think they’re more clear. Like Humpty Dumpty. 🙂

I’m not denying that unnatural engineered foods may subvert the food reward system. But I think we need to understand the mechanisms by which that occurs. Were I to become an industrial food designer, what would be the features I’d want to put in my food to engineer it for subverting the food reward system? And why do those features work? I think if we understand that we’ll understand a lot about the obesity epidemic.

The experiences of people eating 70% PHD are interesting, I would like to come back to those after I’ve done some more posts on this subject.

You know I agree that our ancestors had to be able to survive and function during times of famine and food scarcity — during very long fasts. In fact I use this to help deduce the parameters of our diet. The amount of ketones generated during fasting, plus the amount of glycerol released from triglycerides and the amount of gluconeogenesis that is done, helps to indicate the body’s glucose requirement on normal diets.

As I said to JS, there’s some art in inferring adult diets from the optimal infant diet. But it’s a start. As for the bovine example, after passage through the rumen the bovine grass diet is not so different from cow’s milk! Indeed, adult cattle could probably do OK on cow’s milk.

Hi Daniel,

JS is the master right now at elucidating appetite.

It’s amazing that some of the low carb guru’s are calling you dogmatic and a zealot Paul! Hilarious considering you are probably the kindest, most thoughtful and precise blogger out there in the Paleosphere.

They obviously have not read your book, taken a better look an the evidence or read some of the great anectodes on the blog… my own included. VLC sucked the life out of me… maybe I didn’t do it right but for a young active male it is a definite no go for me and I never had dandruff until I went ZC…. Got way better with starches and is now on it’s way out with starches plus antifungals!

“I’m willing to create my own definitions when I think they’re more clear. Like Humpty Dumpty. ”

You are free to define things the way you want, but you might then be arguing against something someone else is not saying…

Almost everyone I see arguing against FR is pronouncing and spelling it the same as Stephan is, but defining it differently in their argument, then saying it is wrong.

“I think a healthy person eating nourishing food experiences nothing that “reinforces its own consumption.”

What about a person who is full, satisfied and has no need for another molecule of anything as they eat PHD 24/7.

Then they are confronted with a heaping plate of chocolate glazed donuts. You are saying that they will not eat one or two or three, and if they did it means they are “seeking” the trans fats…? I am trying to think of a plausible brain mechanism that would prevent this behavior based on “nutritional needs being satisfied” As I said, the concept of reward does not require the nutrition to be necessary. Quite the contrary. It could only be calories and flavor, neither of which is needed..

Thanks for your comments.

I have been eating the PHD for a while, and it has really reduced any sort of cravings and tendency to mow down, even if the food is really yummy. But indeed, I will down a bag of potato chips in an instant, because it is just that cracktastic, pretty much designed to stimulate me in every possible way.

However when I was younger I would eat Mcdonalds for breakfast, pizza for lunch, and subway for dinner and there was also no compulsion to overeat, it was kind of like what Tom Naughton did, I just ate a moderate amount of junk. Perhaps I would eat the chips now, but if I ate them every day for months, and other foods like that, I think that there would be a point of habituation where it is just that much less stimulating and it’s really less of a big deal. The stipulation is that I have to keep my leptin signaling. I think that leptin resistance is a significant factor in that whole phenomenon of desire more, and anticipating it, regardless of liking. Paul agreed with me when I posted this rat study ajpregu.physiology.org/content/296/3/R493.long, I don’t know if he still does. It basically shows that leptin is needed to regulate the food reward system, and when there is leptin resistance the neurons keep firing and don’t stop, like in the case of magnesium deficiency in anxiety. You don’t have the counter-regulatory system and you get that guy who is full but can’t stop eating, to a point. All rats tended to eat more than they needed, but then again even control rats probably aren’t getting extremely healthy food, just not so bad that it completely messes them up.

The problem with the methodology is that the food that is hyper-palatable and becomes a preference is also the food that destroys leptin signaling, so it is hard to extricate the two and see which one is really at the root of it. Paul said it best the first time we talked about it, if you take people and give them a cafeteria diet but use rice flour, butter, glucose and other non-toxic ingredients in the context of good health and nutrition, will they turn into Homer Simpson at a buffet? Maybe for a little bit, but for their whole life? It is hard to say. That’s the question. I’m glad that Stephan acknowledges that palatability doesn’t = pernicious food reward-related phenomenon.

I am currently on the GAPS diet, which means that I’ve cut out all of those safe starches for a good while. Seems to me that everyone on either side of the yes-to-safe-starch/no-to-safe-starch argument endorses GAPS.

Any thoughts on why everyone’s ok with skipping safe starches while on the GAPS diet?

P.S. I haven’t read enough about food reward, but during the intro, you are definitely eating a reduced food reward diet.

“What about a person who is full, satisfied and has no need for another molecule of anything as they eat PHD 24/7.

Then they are confronted with a heaping plate of chocolate glazed donuts. You are saying that they will not eat one or two or three, and if they did it means they are ‘seeking’ the trans fats…? I am trying to think of a plausible brain mechanism that would prevent this behavior based on “nutritional needs being satisfied”

the really remarkable thing is, after a short time on paleo/primal/PHD, the desire for those doughnuts just goes away in many people. in my low-fat days of 20 years ago, no way could i have resisted. not being as well-educated in this field as most of you are, i can only state the phenomena, and rely on others to identify the mechanism — but SOME mechanism there must be.

I just read Jimmie’s post, wow, a lot of people chiming in on this, you all got your work cut out for you.

One thing that you and Kurt might differ on is vit C, unless he’s changed his mind. I remember him sounding skeptical to agnostic about the necessity for supplemental vit C in a JM podcast. But that was way back before he stopped blogging in order fight crime or “consult” or whatever.

On the other hand he did write in his recent post, “Yes I would agree with that. Whites and sweets [potatoes] are loaded with ascorbic acid.”

That’s actually a specific thing I’ve changed after reading PHD, adding some vit C supplements.

The method that Mr. Moore used to solicit and post comments about the concept of “safe starches” is fallacious, sensational, and irrelevant.

1. Most of the commenters, scientists included, sorry to say, acknowledged that they did not read or refer to the published work underpinning the PHD and the theory and application of safe starched in select populations.

2. Many commenters did not have the requisite credentials to comment on the science. The allowance of unidentified anonymous solicited no less, commenters, undercut any credibility, whatsoever.

3. The use of ad hominem had no place in the comments, yet was freely encouraged by Mr. Moore.

4. The Drs. Jaminet were not invited to participate and respond on that post. It was a free-for-all for people having COIs with their own businesses, personal interests and marketing campaigns. (The biggest offender seems to be Mr. Moore who comes right out at the top to say that his personal diet – and implicitly, the associated money making cruises that he sells)is paramount to him and importantly, his readers/customers.

The Jaminets have acted as ethical scientists would: they appropriately use the scientific method and follow where the science leads. They have been unfailingly kind, generous and open to criticism, concerns and questions. Where there are uncertainties, ambiguity or weaknesses in their hypotheses, they have freely acknowledged this, have stated their interest in continuing to investigate, and have evidently done so.

I’m personally a fan of the Jaminets for the above reasons.

I also subscribe to most of the concepts in the PHD because of their foundation in the science and evidence – but NOT because I admire the authors.

This is a key distinction that Mr. Moore does not make. His readers should not be fooled by his fundamental mistake.

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the testimony, a number of Jimmy Moore’s gurus are unaware that very low carb can promote fungal infections.

Hi Kurt,

Since Stephan’s terminology keeps changing, I think it’s OK to develop my own. I’ll circle back and address his specific view at a later date. At the moment I’m not trying to refute him, just develop my own perspective.

I think it’s important to remember that there is a “learned” (Pavlovian) component to food reward and desire. But these learned desires can be unlearned with time, and many people on PHD are reporting that this has happened for them, usually the ones who have been on it longest, 9+ months.

See tess’s comment below for instance.

Hi Stabby,

Great comment, thanks as always for your insight.

I do agree about the leptin point. I confess there are so many angles to this obesity disorder that it’s hard for me to keep everything straight, especially as I have about one hour per week to think about it. I do believe that leptin resistance is the key to obesity, it happens early on and nearly every other defect we see in obesity follows from the leptin resistance. I did a post once (How do Cells Avoid Obesity) showing that leptin resistance automatically leads to insulin resistance.

Hi Ruth,

GAPS is a good diet in the sense that it embodies a lot of lore about how to overcome many digestive ailments, but it does not eliminate the risks of zero-carb dieting.

See for instance this comment from Bella: http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=2998#comment-32197. Bella doesn’t name the “gut healing diet” but I believe it was GAPS. She developed a fungal infection on zero-carb and it was cured by adding starches.

Hi tess,

Thanks so much for sharing your experience. It’s very helpful.

Hi Sean,

I think vitamin C supplementation is a good prophylactic. It may not be necessary, but deficiency is so insidious that if you don’t supplement you may be seriously harming your health without knowing it.

Hi aek,

Thanks for your support. Some of the responses were disappointing, I was expecting a higher level of scientific engagement. However, I still think the conversation will be useful.

“Some of the responses were disappointing, I was expecting a higher level of scientific engagement.”

Yeah, Uffe Ravnskov was especially flippant, too bad about that.

Agree fully with the concept of starch being vital to good health (for already healthy people).

It amazes me how many people miss the whole point of the paleo/ancestral diet. We know so little about the human body, so the safest thing to do is to eat the way we think we evolved to eat. AFAIK, humans/hominids have been eating starchy tubers for millions of years. That makes sense because, if you know what you’re looking for, it’s a meal sitting there waiting to be plucked out of the ground. For example, every time I walk in the woods, I see cattails and wild rice everywhere and I know that I could collect thousands of calories of starch per hour. Should that be telling?

Some of the responses on Jimmy’s site show to the ignorance of these supposed “experts.” The concept that glycemic index matters for anyone who is not already suffering from some sort of metabolic syndrome is totally unsupported by the existing data. Stephan wrote a good post about it a while back.

I don’t know whether LC has a place for people with damaged metabolisms but I suspect it might help, at least initially. While treating the diseases is important, I think it is about time scientists focus more on preventing those diseases. Eating the PHD is pretty close to what I consider ideal.

It’s good that you are being politic (though I don’t think many of those “experts” deserve it) while sticking to your guns too. I hope you manage to convince some people.

Seems to me that FR relates to both an evolutionary and a learned perspective. Some tastes likely mean high calories to our brain, and so it seems plausible that our brain might encourage us to keep eating to prepare for the famine that never comes.

As an aside re industrial foods, I think there’s something particularly problematic about salt, sugar and fat together. Yesterday on Twitter, Andy Bellati pointed out that a Panera wild blueberry scone has 900 milligrams of sodium!

But as someone who has been an outlier on the overeating side, it’s clear that evolutionary FR can go haywire as fight or flight becomes fight or flight or food. This may solely be learned or it may involve brain development and/or genetics and thus not affect everyone equally (I found Gabor Mate’s video* on brain development and addiction very compelling).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpHiFqXCYKc

Stabby and tess, I’m with you. I’m 77 and over the years, I’ve tried to lose weight by going low carb. The weight losses were successful, but I didn’t stop craving high carb/sugary stuff and would always gradually go back to the bad old ways and gain the weight back.

One year later strictly following the PHD, I lost almost 40 lbs and not only don’t I crave carbs and sugar, I am actually repelled by the smell of a bakery. Yeast and cinnamon are off putting. When grocery shopping, just knowing that I have a visible rib cage is enough to keep me moving out of the cookie aisle.

Whether it’s self-hypnosis or balanced nutrition, I say thank you to Paul and Shou-Ching and all the people who comment here.

Paul,

On the breast milk point, Cynthia Kenyon (who of course isn’t the first or only person to mention this) talks about growth vs maintenance & repair.

@Paul

“I think it’s important to remember that there is a “learned” (Pavlovian) component to food reward and desire. But these learned desires can be unlearned with time, and many people on PHD are reporting that this has happened for them, usually the ones who have been on it longest, 9+ months.”

I don’t disagree with this, but this phenomenon would not in any way invalidate the concept. In fact, it reinforces it.

I saw tess’ comment. Again, I do agree that we can unlearn our tendency to overeat junk. But that only reinforces the concept that there is something to be reconditioned from – to be unlearned. That is, that absent conscious effort to eat properly and avoid certain rewarding foods, they may still be able to subvert our physiology if we have them around.

I see a sort of cartesianism in the resistance to arguments about food reward. As if there is something unseemly or messy about the idea that food is a cultural social and psychological thing, and not just chemicals interacting with overdetermining brain circuits.

I don’t want to clog up your blog with more FR arguments, but the idea that being “perfectly” nourished will make you 100% resistance to glazed donuts, marlboros, homemade chocolate chip cookies, or any other nuisance substance seems dubious.

By the way, why do the Kitavans smoke? Is there carb intake to high ? : )

If they are well-nourished, why don’t they just spontaneously unlearn to crave cigarettes? I know. nicotine – dopamine. That’s different than junk food – dopamine. Or is it?

After approximately six months of PHD I have zero craving for sweets and have easily resisted entire tables groaning with plates of cakes, doughnuts, cookies and so forth. Resisted is the wrong word though – it’s as if all desire for a (formerly craved) substance has left my body. I’m not sure if it’s related, but I have no desire to drink alcohol these days.

Hi Paul,

I’m amazed at how few folks commenting in that blog post even seem to understand the simple concept of a “safe starch”. Far too many strawmen cluttering the hot mess.

Unfortunately too many seem to buy into this notion that the occasional foray into blood glucose levels over 150 mg/dL — or even 100 mg/dL — leads to rampant glycation.

Too bad Jimmy couldn’t break up the massive data dump into a few posts and/or have left out those from folks who admitted up front they were unfamiliar with the topic.

Ev 🙂

Carbs watching is a good start to a solid diet. There is so much more that’s needed though. I usually read up on these things before committing to any type of diet. There’s a great site called http://GetYourDiet.com that talks about the hottest new trends out there. My favorite is http://getyourdiet.com/review/xtreme-fat-loss-diet/

Ruth — it’s anecdotal, but all four people in my family experienced a variety of new symptoms (seasonal allergies, constipation, worsening of heartburn, bladder spasms, dry eyes, increasing tiredness and low energy) when we did GAPS. These problems didn’t resolve until we luckily stumbled upon PHD and added back safe starches. I think GAPS would be much improved by allowing more PHD safe starches and doing away with all the honey and nuts which are considerably harder on many people’s systems (they definitely are on mine!) than potatoes and white rice.

So good to see my 3 favorite thinkers in one spot. I am a 64 year old woman who has fought weight control all my adult life. January 2011 I started following Dr. Harris’ 12 steps, J Stanton’s “Eat Like a Predator” and the Jaminets PHD. I am maintaining my weight loss without cravings or white knuckling and feel great. Thank you! Thank you! I have printed out so much from each of your blogs and share with all who ask. My husband is also on board. I may even take up hunting this season!

Here is a stupid question from a layman…

What role does fructose play in food reward? My understanding is that fructose will depress satiety, with the evolutionary purpose of letting us eat a lot of fruit or berries when we stubmle upon a ripe tree/bush. Our liver then converts that furctose to fat right away for storage for the upcoming winter. If our ancensors were lucky enough to find a bush with lots of fructose-containing ( ~fat-containing) berries, they’d do well to eat as much as they could.

Does this mechanism of fructose fall within the framework of the FRH? Or is it totally non-related? Or does my thought make no sense what-so-ever?

Louis CK explaining what food reward is.

Be warned, he is (just slightly) crude.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8NI1pcIeYI

@macoda

Here’s a probably stupid answer from an also layman. After writing a ton of crap about food reward without really doing the legwork I think the important division is liking, wanting (incentive salience, hedonic impact)and learning. So in the case of fructose we have heightened sweetness–liking, and perhaps depressed satiety–increased wanting and this is all tied into learning, getting a fructose high, or just easy calories (TNSTAAFL) or whatever. The interactions between these basic delineations is very recursive and poorly understood but that’s how I see fructose fitting into FRH.

Evelyn said:

“Unfortunately too many seem to buy into this notion that the occasional foray into blood glucose levels over 150 mg/dL — or even 100 mg/dL — leads to rampant glycation.”

Too bad Jimmy did not consult Dr. Davis: )

But yes, the “all glucose elevations above baseline are pathologic ” meme seems to have a life of its own independent of the CIH.

Unlike the CIH, though, it only takes 15 minutes on pubmed to learn what normal physiology is, so there is really no excuse for it.

When I was VLC at about 7% carbs, I did a home OGTT with three medium baked potatoes, eaten boiled and plain in the fasting state. I estimate 100 g of carbs. I made no attempt to carb pre-load.

Baseline BG 86. My pp BG peaked at 155 at 45 minutes and was at maybe 115 by 2 hours, and under 100 by 3 hours. I did not have any physical illness from this, psychosomatic or otherwise, but they were not too tasty.

These results were concordant with a study done on healthy japanese males with normal glucoregulation who were all in their 20s. Even once carb- adapted, they had morning breakfast pp peak BG measurement of around 120. Not abnormal.

Now I would venture that many of Jimmy’s readers, or followers of low carb gurus who eat VLC, would conclude that they have damaged metabolisms if they did the same test I did, and with these numbers would conclude that they could not tolerate carbs any more, would gain fat from insulin spikes, get cataracts, etc.

But I went from 7% to 40% carbs and did not gain an ounce, and my fasting BG went down.

This experiment, and subsequent perusal of the literature, is what first made me think that being VLC is self-defeating in the blood glucose spike realm.

Because if you eat VLC most of the time, and slip up or cheat now and then, you have no advantage in terms of AUC for glucose at glycating levels over being less IR by regularly eating carbs. VLC with cheats may have more BG levels over 120 for longer than if you just eat 50 g carbs with each meal. As long as your beta cells are not shot, the amount of glycation on VLC is not going to be any better, and you run the risk of all those other hazards Paul is talking about.

My main concern is that infants are not miniature adults. The metabolism of the infant brain is quite different from that of adults, so I don’t place much stock in the nutritional composition of breast milk, except as it relates to feeding babies.