Mario Renato Iwakura’s guest series on the place of iodine and selenium supplementation in treatment of hypothyroidism continues. This is part 2. Thank you Mario! – Paul

UPDATE November 2023: Since this article was written, PHD recommendations for iodine have become firm. We recommend consistent daily supplementation in the range of 150 to 225 micrograms (not milligrams) per day, plus frequent seafood consumption. The supplementation (a) ensures a healthful supply of iodine and (b) accustoms the thyroid to the presence of iodine which minimizes the risk of thyroid injury from intake of a large amount of iodine at once, possibly at a time of selenium deficiency, for example from an all-you-can-eat crab buffet. Supplementation of >1 mg high doses of iodine carries a high risk of thyroid injury, making some parts of the thyroid hypothyroid and possibly also creating nodules with hyperthyroid activity. … Although our recommendations are not in line with Mario’s, nevertheless Mario’s article is fascinating, and a few people have reported benefit from high-dose iodine. Please read his article and judge for yourself! Best, Paul

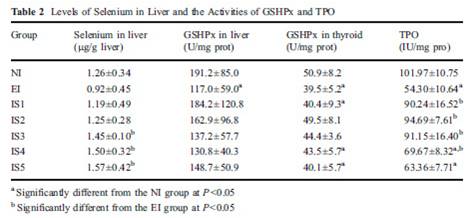

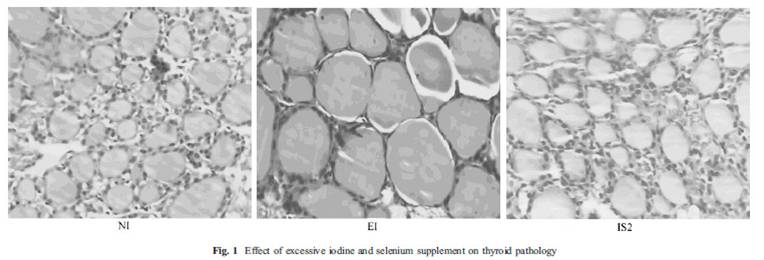

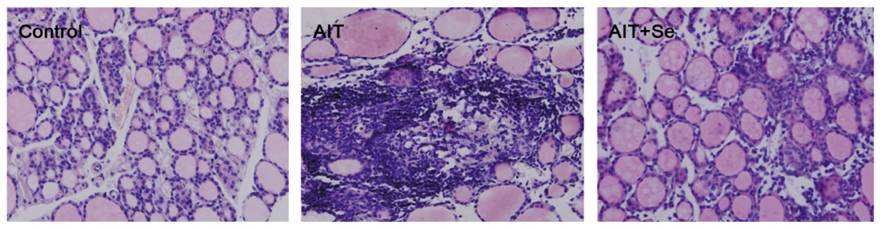

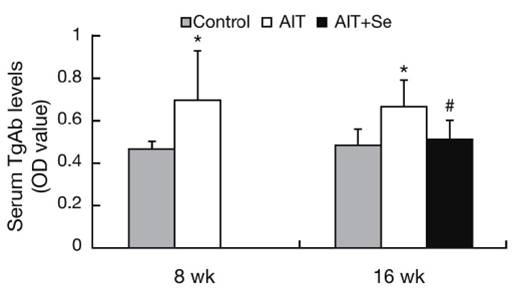

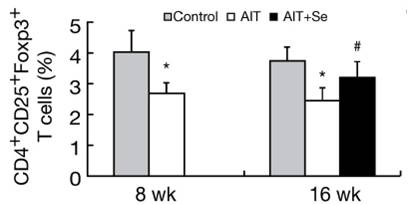

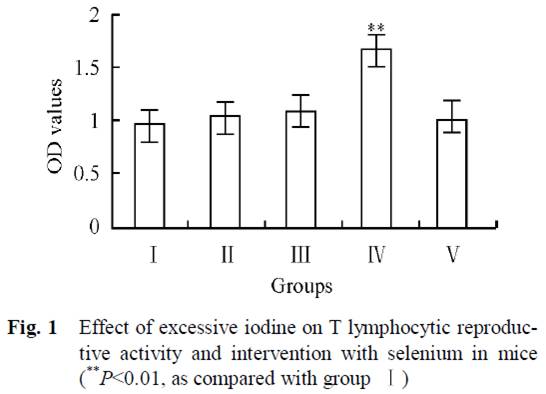

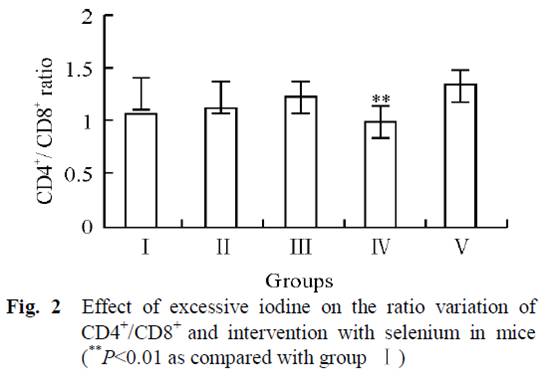

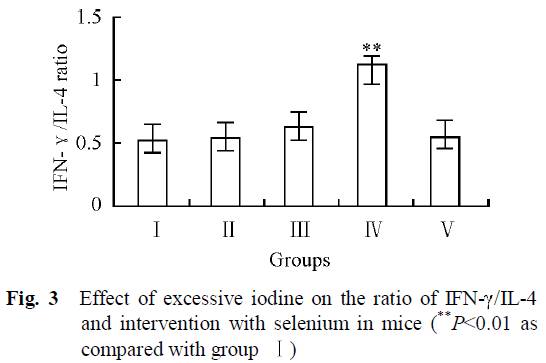

In Part I (Iodine and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis, Part I, May 24, 2011) we looked at evidence from animal studies that iodine is dangerous to the thyroid only when selenium is deficient or in excess, and that optimizing selenium status allows the thyroid to tolerate a wide range of iodine intakes. In fact, there were some hints (such as an improved CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio) that high iodine, if coupled with optimal selenium, might actually diminish autoimmunity.

If that holds in humans too, we should expect that populations with healthy selenium intakes should see a low incidence of thyroid disease and no effect from iodine intake on the incidence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Is that the case?

Korean Study

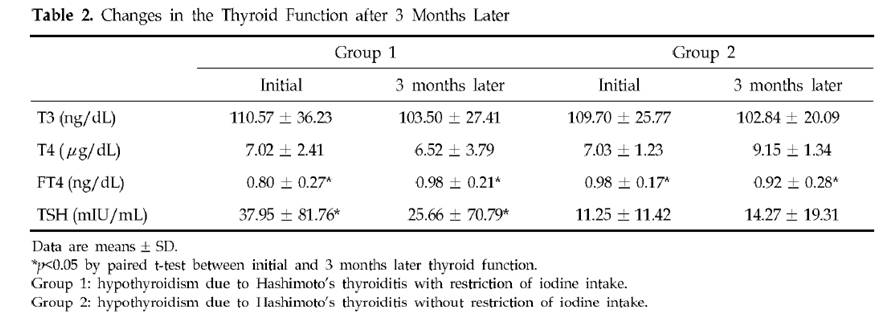

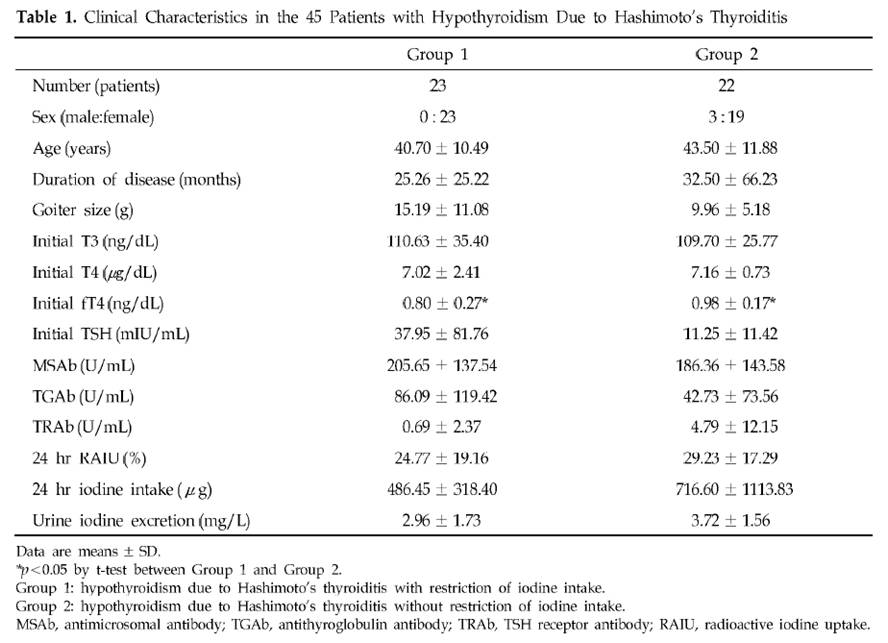

Dr. K [1] quotes a Korean study [3] of Hashimoto’s patients. Half restricted iodine intake to less than 100 mcg/day, the other half ate their normal seaweed and iodine. Of the 23 patients who restricted iodine, 18 (78%) became euthyroid in the sense of having TSH below 4.43 mIU/L, while only 10 (46%) of the 22 that did not restrict iodine became euthyroid. There was no measurement of symptoms at all, and no report of thyroid antibody titers after iodine restriction, so we don’t know if the iodine restriction relieved the underlying autoimmune disorder.

The selection of subjects for the two groups was odd. Group 1, the iodine restricted patients, had an extremely wide range of starting TSH, averaging 38 mIU/L but with a standard deviation of 82 mIU/L. Since all subjects began with TSH above 5 mIU/L, it’s clear that many of the Group 1 members had TSH near 5 and others had TSH well over 100 mIU/L. In comparison, Group 2, the controls, averaged a TSH of 11 mIU/L with a standard deviation of 11 mIU/L – less than 1/7 the standard deviation of Group 1. Few Group 2 members had a TSH above 30.

Table 2 presents the results. Mean TSH in Group 1 was reduced a little, but it did not even come close to normal. Since 78.3% of Group 1 had TSH below 4.43 mIU/L after 3 months, the other 21.7% had to have averaged a TSH above 102.2 mIU/L at the conclusion of the study. The standard deviation of Group 1 TSH at the end of 3 months of iodine restriciton was 71 mIU/L.

Meanwhile, Group 2 members still had a much lower standard deviation at the end of the study: 19 mIU/L.

A conclusion of this study was that “the initial serum TSH concentration was significantly lower in the recovered patients than in the non-recovered patients, which suggests that the possibility of recovvery is increasingly rare as the initial hypothyroidism becomes more severe.” Since Group 1 originally had a much larger fraction of members with very low TSH than Group 2 (plus a few with extremely high TSH to raise the average TSH), and the definition of recovery was a reduction of TSH to 4.43, perhaps it is not surprising that a higher fraction of Group 1 recovered.

Further calling into question the conclusion that lower iodine intake is beneficial is another observation. Looking at Table 1, we see that Group 2 (controls) had, at baseline, much higher iodine intake and higher urinary iodine excretion. Despite this, goiter size, TSH, antimicrosomal (MSAb) and antithyroglobulin (TGAb) antibodies were all lower!

A Japanese Study

A similar study with similar results was done in Japan [4].

In Asia, high iodine intake is due to high consumption of seaweed. Seaweed is high in naturally produced bromine compounds [5][6][7], arsenic [9][12][13], and mercury [9], and can accumulate radioactive iodine [8][9][10][11]. All these substances are known to interfere with thyroid function.

Bromide levels in urine in Asia are very high and are associated with seaweed consumption [6][7]. Values of 5 to 8.1 mg/l have been observed among Japanese, and 8 to 12 mg/l among Koreans.

It is quite possible that any benefits from “iodine restriction,” i.e. seaweed restriction, were due to reduced intake of bromine, arsenic, mercury, and radioactive iodine.

A China Study

Dr. Kharrazian [2] cites a study done in China [14] comparing three different areas: one with iodine deficiency (Panshan), another where iodine is more than adequate (Zhangwu) and a third where iodine is excessive (Huanghua). More than adequate and excessive iodine was associated with increased risk for subclinical and overt hypothyroidism.

But, another study [15], done in the same regions, showed that, coincidentally, Huanghua, the region with excessive iodine, and Zhangwu, the region with more than adequate iodine, had lower median serum selenium concentrations than Panshan, where iodine was deficient. Blood selenium concentrations were 83.2, 89.1 and 91.4 microg/L, respectively. So iodine consumption was inversely related to selenium consumption. Was it lower iodine, or higher selenium, that was beneficial?

TPOAb antibody levels were inversely associated with selenium levels. Patients with the highest TPOAb antibodies (>600 UI/ml) had lower selenium levels than patients with moderate and lower TPOAb antibodies (respectively 83.6, 95.6 and 92.9 UI/ml). [15]

Studies from Brazil, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Greece

Dr K also cites a rise in Hashimoto’s incidence in Brazil, Sri Lanka, Turkey and Greece after salt iodinization began. Are these countries deficient in selenium? Well, lets see:

Brazil: The study was done in São Paulo, a city with a large Brazilian-Japanese population. Brazilian-Japanese have significant lower levels of Se than Japanese living in Japan [16].

Greece: Selenium status is one of the lowest of the Europe [17].

Turkey: Selenium status of Turkish children is found to be unusually low, only 65 ng/ml in boys and 71 ng/ml in girls [18]. Turkey is characterized by widespread iodine deficiency and marginal selenium deficiency [19].

Sri Lanka: Significant parts of the Sri Lankan female population may be selenium deficient [20].

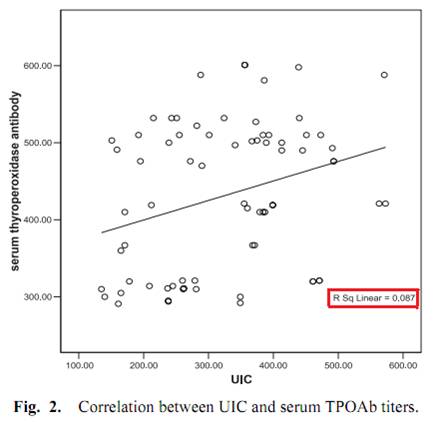

One study, done in Egypt, measured iodine excretation in urine and its relation with thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) [21]. Although the abstract said that a significant correlation was found, this is far from reality, as we can see from Fig. 2.

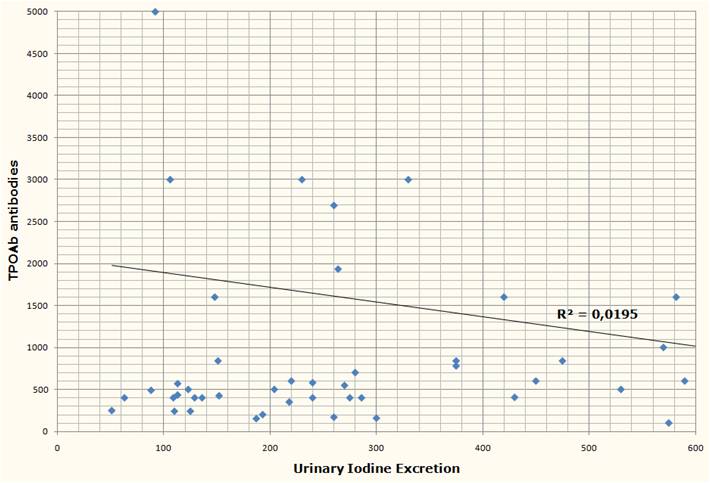

Another study from Brazil [2] measured urinary iodine excretation and serum TPOAb and TgAb antibodies from 39 subjects with Hashimoto’s, none of whom were receiving treatment at the time of the study. Both antibody titers had no obvious correlation with urinary iodine.

Two discordant epidemiological studies

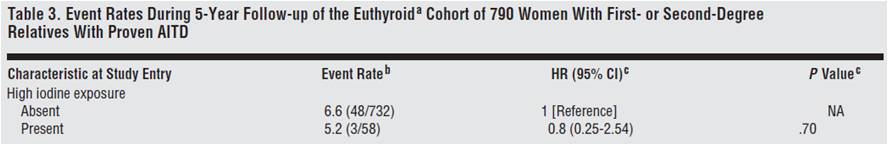

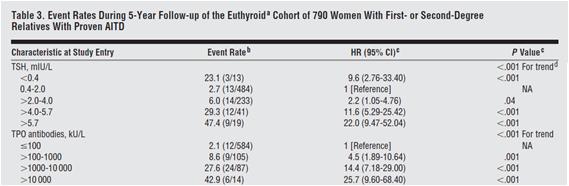

From the Netherlands, we have a prospective observational study looking at whether the female relatives of 790 autoimmune thyroid disease patients would progress to overt hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism [22].

Although the relationship was not considered statistically significant, they found that women with high iodine intake (assessed through questionnaires) were 20% less likely to develop thyroid disorders.

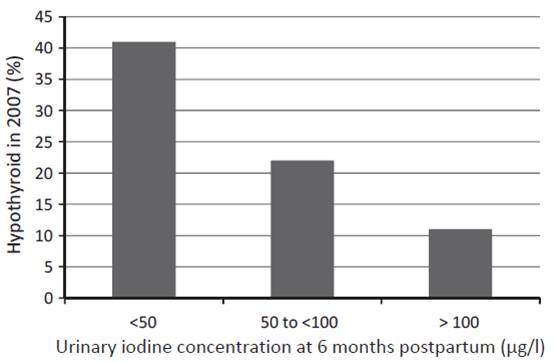

Another study from western Australia (a region that has previously been shown to be iodine replete) measured urinary iodine concentration (UIC) of 98 women at 6 months postpartum and checked their thyroid status both postpartum and 12 years later [23]. UIC at 6 months postpartum predicted both postpartum thyroid dysfunction and hypothyroidism 12 years later:

The researchers concluded:

The odds ratio (OR) of hypothyroid PPTD with each unit of decreasing log iodine was 2.54, (95%CI: 1.47, 4.35), and with UIC < 50 lg/l, OR 4.22, (95%CI: 1.54, 11.55). In the long term, decreased log UIC significantly predicted hypothyroidism at 12-year follow-up (p = 0.002) … The association was independent of antibody status.

In short, the more iodine being excreted (and thus, presumably, the more in the diet and in the body), the less likely were hypothyroid disorders – not only at the time, but also 12 years later.

Dangers of selenium supplementation in iodine deficiency.

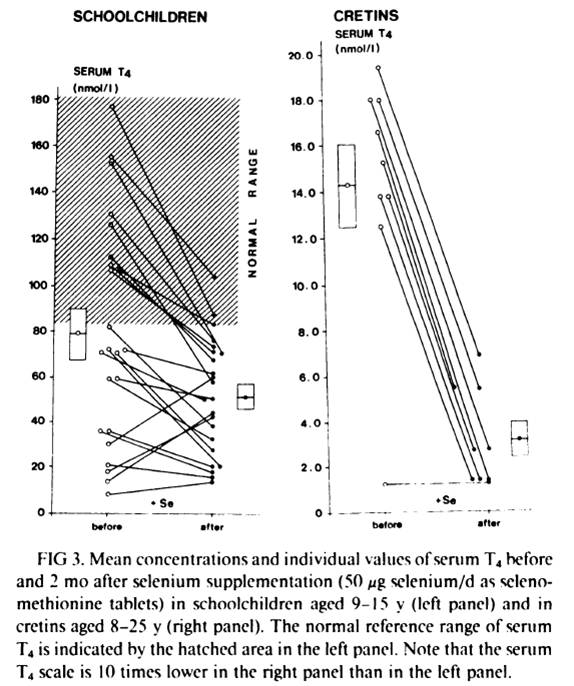

Selenium supplementation when iodine and selenium deficiencies are both present can be dangerous, as the experience in northern Zaire, one of the most severely iodine and selenium deficient population in the world, shows [25].

Schoolchildren and cretins were supplemented for 2 months with a physiological dose of selenium (50 mcg Se per day as selenomethionine). Serum selenium was was very low at the beggining of the study and was similar in schoolchildren and in cretins (343 +- 190 nmil/L in schoolchildren, n=23, and 296 +- 116 nmol/L in cretins, n=9). After 2 months of selenium supplementation, the massive decrease in serum T4 in virtually every subject can be seen in fig. 4 below:

In schoolchildren, serum free thyroxin (fT4) decreased from 11.8 +- 6.7 nmol/L to 8.4 +- 4.1 nmol/L (P<0.01); serum reverse triiodothyronine (rT3) decreased from 12.4 +- 11.5 nmol/L to 9.0 +- 7.2 nmol/L; mean serum T3 and mean TSH remained stable. In cretins, serum fT4 remained the same or decreased to an undetectable level in all nine cretins; mean serum T3 decreased from 0.98 +- 0.72 nmol/L to 0.72 +- 0.29 nmol/L, and two cretins who were initially in a normal range of serum T3 (1.32-2.9 nmol/L) presented T3 values outside the lower limit of normal after selenium supplementation; mean serum TSH increased significantly from 262 mU/L to 363 mU/L (p<0.001).

Another previous similar trial, this time done in 52 schoolchildren, reached the same results: a marked reduction in serum T4 [26][27]. This previous trial “was shown to modify the serum thyroid hormones parameters in clinically euthyroid subjects and to induce a dramatic fall of the already impaired thyroid function in clinically hypothyroid subjects” [27].

What stands out is the difference in the results between euthyroid schoolchildren and cretins/hypothyroids. Two months of selenium supplementation was probably not enough time to affect significantly the thyroid of the euthyroid schoolchildren (althougt already impacted T4 and fT4). But, in cretins and hypothyroids, where the thyroid was already more deficient, the impact was evident.

Conclusion and What I Do

Iodine and selenium are two extremely important minerals for human health, and are righly emphasized as such in the Perfect Health Diet book and blog. I believe they are fundamental to thyroid health and very important to Hashimoto’s patients.

A survey of the literature suggests that Hashimoto’s is largely unaffected by iodine intake. However, the literature may be distorted by three circumstances under which iodine increases may harm, and iodine restriction help, Hashimoto’s patients:

- Selenium deficiency causes an intolerance of high iodine.

- Iodine intake via seaweed is accompanied by thyrotoxic metals and halides.

- Sudden increases in iodine can induce a reactive hypothyroidism.

All three of these negatives can be avoided by supplementing selenium along with iodine, using potassium iodide rather than seaweed as the source of iodine, and increasing iodine intake gradually.

It’s plausible that if iodine were supplemented in this way, then Hashimoto’s patients would experience benefits with little risk of harm. Anecdotally, a number have reported benefits from supplemental iodine.

Other evidence emphasizes the need for balance between iodine and selenium. Just as iodine without selenium can cause hypothyroidism, so too can selenium without iodine. Both are needed for good health.

A few months after I was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s I started 50 mg/day iodine plus 200 mcg/day selenium. If I were starting today, I would follow Paul’s recommendation to start with selenium and a low dose of iodine, and increase the iodine dose slowly. I would not take any kelp, because of potential thyrotoxic contaminants.

Currently I’m doing the following to try to reverse my Hashimoto’s:

- PHD diet and follow PHD book and blog advices to enhance immunity against infections, since infections seems to be implicated in Hashimoto’s pathology [28][29][30]. I give special attention to what Chris Masterjohn calls “traditional superfoods”: liver and other organs, bones and marrow, butter and cod liver oil, egg yolks and coconut, because these foods are high in minerals, like iodine, zinc, selenium, copper, chromium, manganese and vanadium, all of which seems to play a role in thyroid health [31];

- High dose iodine (50mg of Lugol’s) plus 200 mcg selenium daily. These I supplement because of their vital importance to thyroid and immune function;

- 3 mg LDN (low dose naltrexone) every other day to further increase immunity. LDN resources are listed below [32][33][34][35][36];

- Avoiding mercury and other endocrine disruptors. When I removed 9 amalgams (mercury), my TPO antibodies increased for 3 months and took another 6 months to return to previous values. I also avoid fish that have high and medium concentrations of mercury. Cod consumption increased my TPO antibodies;

- 1g of vitamin C daily. Since it seems to confer some protection against heavy metal thyroid disfunction [37], improve thyroid medication absorption [38] and there is some evidence that it could improve a defective cellular transport for iodine [39];

- Donating blood 2 to 3 times per year. In men, high levels of iron seems to impact thyroid function [40].

Final Thanks

I would like to make a special thanks to Paul Jaminet for giving me the opportunity to write this essay, for gathering many, many papers for me, and for having the patience to revise both posts and suggest many changes that made the text clearer; and to Emily Deans who kindly sent me one key study that Paul could not get.

References:

[1] Dr Datis Kharrazian. Iodine and Autoimmune Thyroid — References. http://drknews.com/some-studies-on-iodine-and-autoimmune-thyroid-disease/.

[2] Marino MA et al. Urinary iodine in patients with auto-immune thyroid disorders in Santo André, SP, is comparable to normal controls and has been steady for the last 10 years. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2009 Feb;53(1):55-63. http://pmid.us/19347186.

[3] Yoon SJ et al. The effect of iodine restriction on thyroid function in patients with hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Yonsei Med J. 2003 Apr 30;44(2):227-35. http://pmid.us/12728462.

[4] Kasagi K et al. Effect of iodine restriction on thyroid function in patients with primary hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2003 Jun;13(6):561-7. http://pmid.us/12930600.

[5] Gribble GW. The natural production of organobromine compounds. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2000 Mar;7(1):37-47. http://pmid.us/19153837.

[6] Zhang ZW et al. Urinary bromide levels probably dependent to intake of foods such as sea algae. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001 May;40(4):579-84. http://pmid.us/11525503.

[7] Kawai T, Zhang ZW et al. Comparison of urinary bromide levels among people in East Asia, and the effects of dietary intakes of cereals and marine products. Toxicol Lett. 2002 Aug 5;134(1-3):285-93. http://pmid.us/12191890.

[8] Leblanc C et al. Iodine transfers in the coastal marine environment: the key role of brown algae and of their vanadium-dependent haloperoxidase. Biochimie. 2006 Nov;88(11):1773-85. http://pmid.us/17007992.

[9] van Netten C et al. Elemental and radioactive analysis of commercially available seaweed. Sci Total Environ. 2000 Jun 8;255(1-3):169-75. http://pmid.us/10898404.

[10] Hou X et al. Iodine-129 in human thyroids and seaweed in China. Sci Total Environ. 2000 Feb 10;246(2-3):285-91. http://pmid.us/10696729.

[11] Toh Y et al. Isotopic ratio of 129I/127I in seaweed measured by neutron activation analysis with gamma-gamma coincidence. Health Phys. 2002 Jul;83(1):110-3. http://pmid.us/12075675.

[12] Miyashita S, Kaise T. Biological effects and metabolism of arsenic compounds present in seafood products. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2010;51(3):71-91. http://pmid.us/20595788.

[13] Cleland B et al. Arsenic exposure within the Korean community (United States) based on dietary behavior and arsenic levels in hair, urine, air, and water. Environ Health Perspect. 2009 Apr;117(4):632-8. Epub 2008 Dec 8. http://pmid.us/19440504.

[14] Chong W, Shit Xg, Teng WP, et al. Multifactor analysis of relationship between the biological exposure to iodine and hypothyroidism. Zhongua Yi Za Zhi. 2004 Jul 17:84(14):1171-4. http://pmid.us/15387978.

[15] Tong YJ et al. An epidemiological study on the relationship between selenium and thyroid function in areas with different iodine intake. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003 Dec 10;83(23):2036-9. http://pmid.us/14703411.

[16] Karita K et al. Comparison of selenium status between Japanese living in Tokyo and Japanese brazilians in São Paulo, Brazil. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2001;10(3):197-9. http://pmid.us/11708308.

[17] Thorling EB et al. Selenium status in Europe–human data. A multicenter study. Ann Clin Res. 1986;18(1):3-7. http://pmid.us/3717869.

[18] Mengüba? K et al. Selenium status of healthy Turkish children. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996 Aug;54(2):163-72. http://pmid.us/8886316.

[19] Hincal F. Trace elements in growth: iodine and selenium status of Turkish children. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2007;21 Suppl 1:40-3. http://pmid.us/18039495.

[20] Fordyce FM et al. Selenium and iodine in soil, rice and drinking water in relation to endemic goitre in Sri Lanka. Sci Total Environ. 2000 Dec 18;263(1-3):127-41. http://pmid.us/11194147.

[21] Alsayed A et al. Excess urinary iodine is associated with autoimmune subclinical hypothyroidism among Egyptian women. Endocr J. 2008 Jul;55(3):601-5. Epub 2008 May 15. http://pmid.us/18480555.

[22] Strieder TG et al. Prediction of progression to overt hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism in female relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease using the Thyroid Events Amsterdam (THEA) score. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Aug 11;168(15):1657-63. http://pmid.us/18695079.

[23] Stuckey BG et al. Low urinary iodine postpartum is associated with hypothyroid postpartum thyroid dysfunction and predicts long-term hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011 May;74(5):631-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.03978.x. http://pmid.us/21470286.

[24] American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Evaluation and Treatment of Hyperthyroidism and Hypothyroidism. https://www.aace.com/sites/default/files/hypo_hyper.pdf.

[25] Vanderpas JB et al. Selenium deficiency mitigates hypothyroxinemia in iodine-deficient subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993 Feb;57(2 Suppl):271S-275S. http://pmid.us/8427203.

[26] Contempré B et al. Effect of selenium supplementation on thyroid hormone metabolism in an iodine and selenium deficient population. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992 Jun;36(6):579-83. http://pmid.us/1424183.

[27] Contempré B et al. Effect of selenium supplementation in hypothyroid subjects of an iodine and selenium deficient area: the possible danger of indiscriminate supplementation of iodine-deficient subjects with selenium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991 Jul;73(1):213-5. http://pmid.us/2045471.

[28] Benvenga S et al. Homologies of the thyroid sodium-iodide symporter with bacterial and viral proteins. J Endocrinol Invest. 1999 Jul-Aug;22(7):535-40. http://pmid.us/10475151.

[29] Wasserman EE et al. Infection and thyroid autoimmunity: A seroepidemiologic study of TPOaAb. Autoimmunity. 2009 Aug;42(5):439-46. http://pmid.us/19811261.

[30] Tozzoli R et al. Infections and autoimmune thyroid diseases: parallel detection of antibodies against pathogens with proteomic technology. Autoimmun Rev. 2008 Dec;8(2):112-5. http://pmid.us/18700170.

[31] Neve J. Clinical implications of trace elements in endocrinology. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1992 Jan-Mar;32:173-85. http://pmid.us/1375054.

[32] David Gluck, MD. Low Dose Naltrexone information site. http://www.lowdosenaltrexone.org/.

[33] LDN Yahoo Group. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/lowdosenaltrexone/.

[34] LDN World Database. Where LDN users share their experience with various diseases. http://www.ldndatabase.com/.

[35] Those Who Suffer Much Know Much. A colection of LDN users testimonies. http://www.ldnresearchtrustfiles.co.uk/docs/2010.pdf.

[36] Elaine A. More. The Promise Of Low Dose Naltrexone Therapy: Potential Benefits in Cancer, Autoimmune, Neurological and Infectious Disorder. http://www.amazon.com/Promise-Low-Dose-Naltrexone-Therapy/dp/0786437154.

[37] Gupta P, Kar A. Role of ascorbic acid in cadmium-induced thyroid dysfunction and lipid peroxidation. J Appl Toxicol. 1998 Sep-Oct;18(5):317-20. http://pmid.us/9804431.

[38] Absorption of thyroid drug levothyroxine improves with vitamin C. The Endocrine Society. News Room. http://www.endo-society.org/media/ENDO-08/research/Absorption-of-thyroid-drug.cfm.

[39] Abraham, G.E., Brownstein, D.. Evidence that the administration of Vitamin C improves a defective cellular transport mechanism for iodine: A case report. The Original Internist, 12(3):125-130, 2005. http://www.optimox.com/pics/Iodine/IOD-11/IOD_11.htm.

[40] Edwards CQ et al. Thyroid disease in hemochromatosis. Increased incidence in homozygous men. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Oct;143(10):1890-3. http://pmid.us/6625774.

Recent Comments