In our book we point out a number of dietary tactics that appear to substantially decrease risk of cardiovascular disease. They include:

- Optimizing tissue omega-6 to omega-3 balance by minimizing intake of omega-6 fats and eating an oily marine fish like salmon or sardines once a week.

- Optimizing various micronutrients including vitamins D and K2, choline, magnesium, iodine, and selenium.

- Reducing carbohydrate intake to the body’s natural level of glucose utilization, about 30% of total calories.

We cited two main sources for the claim that reducing carbohydrate intake reduces risk of cardiovascular disease:

– The Nurses Health Study found that risk of coronary heart disease went down steadily as dietary carbohydrates were reduced and replaced by fat. Those eating a 59% carb diet were 42% more likely to have heart attacks than those eating a 37% carb diet. [1]

– Replacing dietary carbohydrate with saturated or monounsaturated fat raises HDL and lowers triglycerides, changes that are associated with low rates of cardiovascular disease. Blood lipids are optimized when carb intake drops to 30% of energy or less. [2]

I think this is pretty strong evidence. It is not completely bulletproof, because associations don’t prove causation and improving risk factors doesn’t necessarily improve disease risk; but, combined with supportive evidence from cellular biology and clear evidence that evolutionary selection favors a carbohydrate intake around 30%, I consider it convincing.

However, it’s always good to have more evidence; and two new studies provide some. One directly relates utilization of carbohydrates for energy to atherosclerosis, and the other conducted a 12-month clinical trial of a carbohydrate restricted diet.

Carbohydrate Utilization is Associated With Atherosclerosis

Via Stephan Guyenet comes a study that directly links carbohydrate metabolism to atherosclerosis: “Metabolic fuel utilization and subclinical atherosclerosis in overweight/obese subjects.” [3]

The study used intima-media thickness in the carotid artery, which serves the head and neck, as a measure of atherosclerosis. As Wikipedia notes,

Since the 1990s, both small clinical and several larger scale pharmaceutical trials have used carotid artery IMT as a surrogate endpoint for evaluating the regression and/or progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Many studies have documented the relation between the carotid IMT and the presence and severity of atherosclerosis.

To assess metabolism it measured the “respiratory quotient” or RQ. RQ is the ratio of carbon dioxide (CO2) generated in the body to oxygen (O2) consumed in the body.

RQ indicates which fuels are being burned for energy in the body. When carbohydrates are burned, the reaction involves carbon exclusively, so for every O2 molecule consumed there is a CO2 molecule created. This makes the RQ 1.0 when carbohydrates are burned.

Fats, however, donate both carbon and hydrogen, and the hydrogens react with oxygen to make water (H2O). So some of the oxygen consumed when fats are burned goes into water, not carbon dioxide, and the RQ when fats are burned is about 0.7. Ketones also have an RQ around 0.7.

Amino acids from protein have variable amounts of hydrogen and carbon, some amino acids are ketogenic and some are glucogenic, and so the RQ of protein depends on its amino acid mix. Typically RQ from different types of food protein is between 0.8 and 0.9.

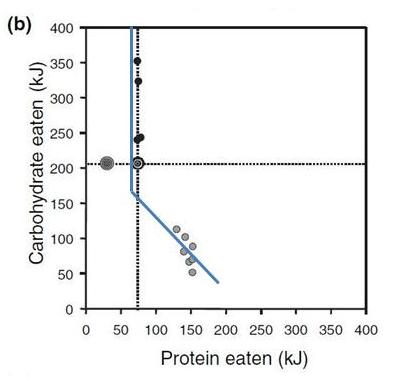

However, most people eat a fairly consistent amount of protein, around 15% of energy, so the variable that generally determines RQ in practice is the ratio of carbs to fat in the diet. Higher RQ indicates a higher-carb diet.

Another study had previously shown that calorie restriction, which also reduces RQ by replacing dietary carbohydrate with fat released from adipose tissue, reduces the thickness of the carotid intima-media. [4] This study was the first testing whether the RQ-CIMT relationship holds also in subjects not known to be restricting calories.

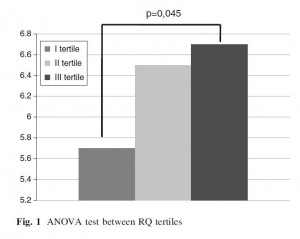

The study found that indeed it does: the lower RQ, the less atherosclerosis the subjects had. Unfortunately they don’t present data in a visually useful way (a scatter plot of RQ vs CIMT would have been helpful); here is what they do show:

RQ was better than waist circumference or BMI at predicting degree of atherosclerosis. Only age was a stronger predictor of atherosclerosis than RQ.

RQ predicted atherosclerosis equally well in subjects with and without obesity. This tells us two things:

- It supports the idea that it was habitual diet rather than recent calorie restriction (which decreases RQ by replacing food-sourced calories with fat from adipose tissue) that generated low RQ and low CIMT.

- As the authors say, it indicates “the main role of metabolic factors rather than BMI” in generating atherosclerosis – metabolic factors meaning burning glucose for energy rather than fat.

It is also supporting evidence for one of the more controversial lines of our book, that “mitochondria prefer fat.”

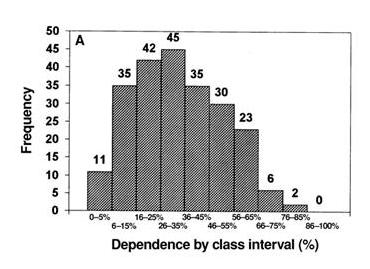

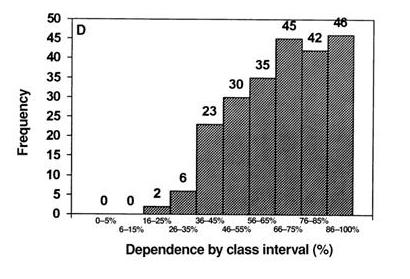

One caution: Most of the subjects in this study were eating diets that were around 50% to 55% carbohydrate, so the study was testing whether it’s better to eat a little above or below this carb intake. It tells us, I think, that a 45% carb diet is healthier than a diet with more than 50% carbs. It doesn’t tell us what carb intake is optimal.

The Clinical Trial

In a trial lasting 12 months, restricting carbohydrates to 600 to 850 calories per day – that is, about the 30% of energy that we recommend – in the context of a slightly hypocaloric diet improved cardiovascular risk factors. [5]

Overweight and obese subjects in the trial lost 2.8 kg (6 pounds) over the year-long trial, so it couldn’t have been severely calorie restricted. Changes in other risk factors:

– Blood pressure dropped from 121/79 to 112/72;

– Fasting blood glucose dropped from prediabetic 106 mg/dl to normal 96 mg/dl;

– Lipids improved, with triglycerides decreasing from 217 to 155 mg/dl and HDL increasing from 39 to 45 mg/dl.

They conclude:

The results of this study indicate that a moderately restricted calorie and carbohydrate diet has a positive effect on body weight loss and improves the elements of metabolic syndrome in patients with overweight or obesity and prediabetes. These results underscore the need to provide dietary recommendations focusing on calorie and carbohydrate restrictions … Our results are in agreement with reports produced by other authors who also assessed a carbohydrate-reduced diet …

Conclusion

A number of simple dietary and nutritional changes appear to reduce the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease generally. One of them is reducing carbohydrate intake.

I believe the optimum carbohydrate intake is around 30% of energy. Many studies generate clear evidence of benefits as carbs are brought down into the range of 20% to 30% of energy, especially in metabolic disorders like metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and obesity. It’s good to see that evidence from other diseases, such as CVD, also supports the same carb intake.

Because most people’s diets are flawed in so many different ways, and fixing an individual factor is often associated with a reduction in CVD risk of 40% to 70%, it’s possible that we could reduce CVD risk by 90% or more by implementing all of the dietary optimizations described in our book.

It’s well worth pursuing all these little optimizations!

References

[1] Halton TL et al. Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 9;355(19):1991-2002. http://pmid.us/17093250.

[2] Krauss RM. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype and diet-gene interactions. J Nutr. 2001 Feb;131(2):340S-3S. http://pmid.us/11160558.

[3] Montalcini T et al. Metabolic fuel utilization and subclinical atherosclerosis in overweight/obese subjects. Endocrine. 2012 Nov 28. [Epub ahead of print] http://pmid.us/23188694.

[4] Iannuzzi A et al. Comparison of two diets of varying glycemic index on carotid subclinical atherosclerosis in obese children. Heart Vessels. 2009 Nov;24(6):419-24. http://pmid.us/20108073.

[5] Velázquez-López L et al. Low calorie and carbohydrate diet: to improve the cardiovascular risk indicators in overweight or obese adults with prediabetes. Endocrine. 2012 Sep 1. [Epub ahead of print] http://pmid.us/22941424.

Recent Comments