Our book has 199 reviews at Amazon.com, and almost 80% of them are 5-star reviews, for which we thank you. But once in a while we get a 1-star review, usually from a vegan. Recently we got a 1-star review from someone named “Victor” which actually cited two papers:

This book recommends eating red meat, white rice, and eggs? Ridiculous. These aren’t healthy foods. They aren’t good for your body.

Red meat and eggs both promote colon cancer. White rice has a terribly high glycemic load and glycemic index, which can increase the risk of getting diabetes.

Evidence:

“Egg consumption and mortality from colon and rectal cancers: an ecological study.”

“Red Meat-Derived Heterocyclic Amines Increase Risk of Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Case-Control Study”

Look up other research studies that support these two. They all go hand in hand.

You can deny the evidence however much you want, but the truth is that red meat, white rice, eggs (as well as dairy products) will NOT promote your health.

Odd: I expect a critic who objects to red meat, eggs, and dairy to be a vegan, but Victor objects to rice too. One wonders what foods Victor doesn’t object to, and whether he manages to eat at all. (UPDATE: Victor is a vegan.)

His objection to red meat is irrelevant to PHD, since heterocyclic amines form at temperatures above 400˚F which do not occur in the gentle cooking methods we advocate. Indeed, our book explicitly warns against cooking methods that generate HCAs on page 234. It’s pretty easy to avoid these cooking methods, because they char meat. Indeed, the study Victor cites is based on a food survey called CHARRED. [1]

The “red meat” category in epidemiological studies includes not only beef and lamb, but pork and processed meats. Industrial foods like processed meats have their own problems which we warn about in our book, and undercooked pork can carry dangerous infections which we also warn about in the book and on this blog.

But none of those caveats touch gently cooked beef or lamb. All the evidence indicates that these are thoroughly healthful foods.

Victor objects to rice because of its high glycemic index, an issue which we’ve addressed in the book and on this blog in the safe starches debate and my post on how to avoid hyperglycemic toxicity.

Which brings us to Victor’s bête noire, eggs. I was curious, so I looked up the study Victor cited linking eggs to colon cancer. [2]

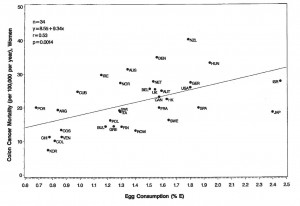

An Association at the Country Level Between Egg Consumption and Colon Cancer

This turns out to be quite a simple paper; the research in it could have been done in a day or two. They gathered some data from two online sources: the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, which has food consumption data for countries, and the World Health Organization, which has health statistics by country. Then they made some scatter plots in Excel, and found an association between eggs and colon cancer. Here it is:

For some reason they included only 34 countries; the FAO and the WHO gather data from nearly every country on earth. They stated, “The selection of the countries was based primarily on the availability of relatively reliable data on mortality from colon and rectal cancers and consumption of eggs, other food groups or nutrients, and cigarettes.” (The “other food groups and cigarettes” – fat, meat, vegetable, fruit, alcohol, and cigarette consumption – were used as adjustment variables in a regression analysis.)

Now, country-level ecological studies have a poor reputation in nutritional epidemiology. One reason is that there are many confounding variables. Foremost among them is income. Health outcomes are strongly dependent on income, with high-income countries eating more animal foods and living longer. But do people live longer because of what they eat, or because they are richer?

Then, when we look at a disease like colon cancer, what we find is that the healthier and longer-lived the country, the more colon cancer cases it has. Cancer is a disease of the elderly, and in societies where people die young, there are few cancer deaths. On the other hand, if some magical food were invented that cured cardiovascular disease, then in countries where that food was eaten cancer would be the leading cause of death. In such a case, we would find consumption of that food to be positively associated with colon cancer rates, even though the food made everyone healthier.

So before one takes an ecological association like the one noted in this paper seriously, it is good to step back and look at the big picture.

As it happens, I have FAO and WHO data in an Excel spreadsheet, so it didn’t take long to make a few charts.

Eggs and Mortality or Life Expectancy

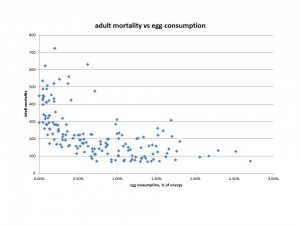

I used 2003-4 data which gave me data from 164 countries for both egg consumption and health outcomes.

Here is the relation between egg consumption and adult mortality. (“Adult mortality” means the probability of dying between ages 15 and 64 per 1000 people.)

There is a clear correlation: more eggs, lower mortality.

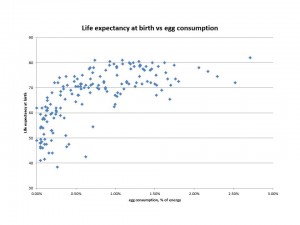

Here is the association between egg consumption and life expectancy:

Again, there is a clear correlation: the more eggs a country consumes, the longer its people live. Note that the country with the highest egg consumption, Japan which obtains fully 2.71% of energy from eggs, has the longest life expectancy.

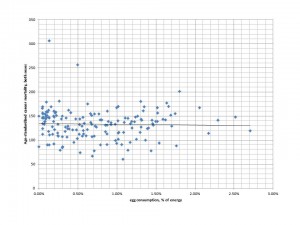

What about the association between eggs and cancer? Here it is, with cancer mortality standardized by age:

Eyeballing it, there seems to be no correlation at all. I’ve had Excel calculate a linear fit here, and it turns out cancer mortality actually seems to decline very slightly as egg consumption increases.

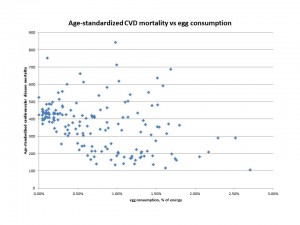

If eggs are associated with lower mortality and longer lifespans, but have no effect on cancer, then you’d expect them to be associated with lower rates of cardiovascular disease mortality. So they are:

Countries with low egg consumption have CVD mortality about double that of countries with high egg consumption.

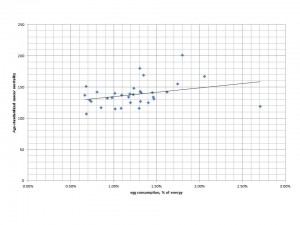

I was curious if reducing the sample from the full set of 163 countries to the 34 used in the paper would alter the data. It does. Here is cancer mortality plotted against egg consumption for the 34 countries included in the paper Victor cited:

In this subset of countries the correlation of egg consumption with cancer mortality is reversed and becomes positive. It looks like the paper chose its countries well, if its goal was to show a negative effect from egg consumption.

Eggs Are a Health Food

One lesson this exercise teaches is that if you look at population-level data for associations, restrict your sample of countries to a subset of the available data, and restrict the health outcome you analyze to a small fraction of the causes of death, you can make any food, including eggs, look bad.

But if one looks at total mortality or life expectancy, eggs seem to be quite a healthful food. Higher egg consumption correlates with lower mortality and longer lifespan. The country in the world with the highest egg consumption, Japan, has the longest lifespans.

Is it plausible that eggs extend lifespan by reducing cardiovascular disease mortality? Yes! Eggs are along with liver the best food source of choline, and choline is a critical nutrient for vascular and metabolic health. Chapter 35 of our book discusses this nutrient.

Is it plausible that eggs promote colon cancer? Not really. There has not to my knowledge been proposed any plausible mechanism by which eggs promote cancer generally or colon cancer specifically.

Since eggs are strongly correlated with lower cardiovascular mortality and plausible causal mechanisms are known, while eggs are correlated with zero change or perhaps a slight reduction in cancer mortality and there is no known mechanism tying them to cancer risk, we should regard eggs as a health food.

To assure adequate choline intake, PHD recommends eating 3 egg yolks per day. They are one of our “supplemental foods” that should be eaten routinely.

Conclusion

Victor seems to have fallen for a rookie mistake: taking associations too seriously.

Positive associations with diseases exist for every food. Consider what would happen if you took a variable totally unconnected to health – say, the mean number of stars above a certain brightness in a country’s night sky – and looked for associations with national health outcomes. Simply by chance, some diseases would show a positive association and some would show a negative correlation. If you only publish the positive associations, you can scare naïve readers into thinking that starlight causes assorted diseases.

And if you repeat the exercise for foods, you could scare naïve readers into avoiding every single food in existence, as Victor has eschewed beef, lamb, eggs, and rice.

Pubmed is a large database, with over 22 million articles. Not all of these articles represent careful work that seeks to establish a robust truth. Many articles are published “for practice,” even if they have nothing useful to say. Graduate students have to learn how to run regression analyses, write papers, and get them published; even senior academics may be rewarded for publishing weak or pointless papers. We shouldn’t let them scare us into a needlessly restricted diet.

References

[1] Helmus DS et al. Red Meat-Derived Heterocyclic Amines Increase Risk of Colon Cancer: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. Nutr Cancer. 2013 Oct 29. [Epub ahead of print] http://pmid.us/24168237.

[2] Zhang J et al. Egg consumption and mortality from colon and rectal cancers: an ecological study. Nutr Cancer. 2003;46(2):158-65. http://pmid.us/14690791.

Recent Comments