Last week in An Anti-Cancer Diet (Sep 28, 2011), I recommended that cancer patients eat 400 to 600 carb calories per day, but combine it with a program of daily intermittent fasting plus longer “ketogenic fasts” and periods of ketogenic dieting or low-protein dieting to promote autophagy.

The recommendation to eat some carbohydrates, plus my statement that it was possible for cancer patients to develop a “glucose deficiency” which might promote metastasis and the cancer phenotype, seems to have stirred a bit of a fuss.

In addition to making @zooko sad, it led Jimmy Moore to reach out to a number of gurus to ask their opinion. On Twitter, Jimmy says:

Working on an epic blog post today about @pauljaminet and his “safe starches” concept. Input from numerous #Paleo and #lowcarb peeps.

I’m excited to have this discussion. As Jimmy later tweeted:

Should be fun to hash all this out publicly for ALL of us to understand better about your concepts. Here’s to education.

So far, I have seen responses from Dr. Kurt Harris and Dr. Ron Rosedale. On PaleoHacks, there is an extensive discussion on a thread started by Meredith.

UPDATE: Jimmy’s post is up: Is There Any Such Thing as “Safe Starches” on a Low-Carb Diet?.

I think this discussion is wonderful. With so many people putting effort into this, I have an obligation to respond. I’ll start with Kurt’s perspective today, then Ron Rosedale’s early next week, then whoever else participates in Jimmy’s epic post.

PHD and Archevore: Similar Diets

Kurt and I have essentially identical dietary prescriptions. However, our reasoning sometimes works from different premises. Kurt observes:

My arguments are based more on ethnography and anthropology than some of Paul’s theorizing, but I arrive at pretty much the same place that he does.

An example of a point of agreement is Kurt’s endorsement of glucose-based carbs:

[I] see the human metabolism as a multi-fuel stove, equally capable of burning either glucose or fatty acids at the cellular level depending on the organ, the task and the diet, and equally capable of depending on either animal fats or starches from plants as our dietary fuel source …

We are a highly adaptable species. It is not plausible that carbohydrates as a class of macronutrient are toxic.

I think that if there is no urgency about generating ATP then fatty acid oxidation is slightly preferable to glucose burning. But essentially, I share Kurt’s point of view. Our ancestors must have been well adapted to consuming high-carb diets, and necessity surely thrust such diets upon some of our ancestors. Certainly there’s no reason why consuming starch per se should be toxic.

Kurt and I also agree on which starches are safe:

These starchy plant organs or vegetables are like night and day compared to most cereal grains, particularly wheat. One can eat more than half of calories from these safe starches without the risk of disease from phytates and mineral deficiencies one would have from relying on grains.

White rice is kind of a special case. It lacks the nutrients of root vegetables and starchy fruits like plantain and banana, but is good in reasonable quantities as it is a very benign grain that is easy to digest and gluten free.

We agree that safe starches are a more useful part of the diet than fruits and vegetables:

[E]ating starchy plants is more important for nutrition than eating colorful leafy greens …

I view most non-starchy fruit with indifference. In reasonable quantities it is fine but it won’t save your life either. I like citrus now and then myself, especially grapefruit. But better to rely on starchy vegetables for carbohydrate intake than fruit.

We agree on the optimal amount of carbs to eat:

I personally eat around 30% carbohydrate now and have not gained an ounce from when I ate 10-15% (and I have eaten as high as 40% for over a year also with zero fat gain) If anything I think even wider ranges of carbohydrate intake are healthy.

One can probably eat well over 50% of calories from starchy plant organs as long as the animal foods you eat are of high quality and micronutrient content.

I think being slightly low-carb, in the sense of eating slightly below the glucose share of energy utilization which I estimate at about 30% of energy, is optimal. However, I think we are metabolically flexible enough that a very broad range of carb intake may be nearly as good. I would consider 10% a minimal but healthy intake of carbs, and 50% a higher-than-optimal, but still healthy, intake so long as the carbs are “safe” and the diet is nourishing.

Differing Origins of Our Ideas

Kurt mentions that his ideas are more derived from ethnography and anthropology than mine.

I give great weight to evolutionary selection as an indicator of the optimal diet, and am friendly to ethnographic and anthropological arguments. If I don’t give tremendous weight to such arguments, it’s because I think some other lines of argument give us finer evidence about the optimal diet.

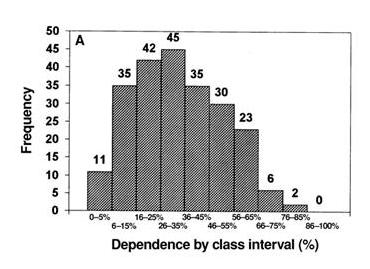

Here, from a paper by Loren Cordain et al [1], are representations of hunter-gatherer diets:

The top graph shows plant food consumption by calories, the bottom graph animal+fish consumption by calories. The numbers are how many of 229 hunter-gatherer societies ate in that range. Typically, hunter-gatherers got 30% of calories from plant foods and 70% of calories from animal foods.

I think the Cordain et al data supports my argument that obtaining 20% to 30% of calories from carbs is probably optimal. However, it’s hardly decisive. There is considerable variability, mainly in response to food availability in the local environment. Inuits, who had few edible plants available, ate hardly any plant foods; tropical tribes with ready access to starchy plants, fruits, and fatty nuts sometimes obtained a majority of calories from plants.

Hunter-gatherer diets, therefore, are a compromise between the diet that is healthy and the diet that is easy to obtain. A skeptic could argue that hunter-gatherers routinely ate a flawed diet because some type of food was routinely easier to obtain than others, and thus systematically biased the diet.

I believe evidence from breast milk is both more precise about what diet is optimal, and much harder for skeptics to refute. Breast milk composition is nearly the same in all humans worldwide, and it has been definitely selected to provide optimal nutrition to infants.

So breast milk, I think, gives us a much clearer indication of the optimal human diet than hunter-gatherer diets. It is an evolutionary indicator of the optimal diet, but it is not ethnographic or anthropological.

There are other evolutionary indicators of the optimal diet — mammalian diets, for instance, and the evolutionary imperative to function well during a famine — which, as readers of our book, we also use to determine the Perfect Health Diet. So, while I think ethnographic and anthropological findings give us important clues to the optimal diet, I think there are plenty of other sources of evidence to which we should give weight. Fortunately, all of these sources of insight seem to be consistent in supporting low-carb animal-food-rich diets — a result which is gratifying and should give us confidence.

Food Reward and Obesity

Kurt seems to have been more persuaded than I am by Stephan Guyenet’s food reward hypothesis (which is, of course, not of Stephan’s creation – it is the dominant perspective in the community of academic obesity researchers). Kurt writes:

Low carb plans have helped people lose fat by reducing food reward from white flour and excess sugar and maybe linoleic acid. This is by accident as it happens that most of the “carbs” in our diet are coming in the form of manufactured and processed items that are simply not real food. Low carb does not work for most people via effects on blood sugar or insulin “locking away” fat. Insulin is necessary to store fat, but is not the main hormone regulating fat storage. That would be leptin.

I agree with Kurt in rejecting what he calls the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity, but I am uneasy at the confident assertion that “reducing food reward” is the mechanism by which excluding flour, sugar, and omega-6 fats helps people lose weight.

Let me say first that there is no doubt that the brain has a food reward system that regulates food intake, and also an energy homeostasis system that regulates activity and thermogenesis, and that these systems are coupled. The brain is the coordinating organ of metabolic activity. And the brain’s food reward and energy homeostasis systems are altered in obesity.

But the direction of causality is unclear. Is “reducing food reward” the best strategy against obesity, or is “maximizing food reward with nourishing food” the best strategy?

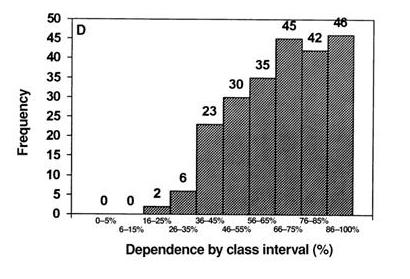

Some data may illustrate what I mean. Here’s an investigation of how the food reward system in rats controls appetite to regulate protein and carbohydrate consumption. The data is from multiple studies and was collected by Simpson and Raubenheimer [2].

Rats were given a chow consisting of protein and carbohydrate in varying proportions. The figure below shows how much of the protein-carb chow they ate.

I’ve drawn a kinked blue line to show what a “Perfect Health Diet” analysis would consider optimal. Protein needs consist of a fixed amount of protein, around 70 kJ, to meet structural needs, plus enough protein to make up any dietary glucose deficiency via gluconeogenesis. Glucose is preferable to protein as a fuel. Glucose needs in rats are in the vicinity of 180 kJ. When dietary glucose intake falls short of 180 kJ, rats eat extra protein; they seek to make carb+protein intake equal to 250 kJ so they can meet both their protein and carb needs, with gluconeogenesis translating the dietary protein supply into the body’s glucose utilization as necessary.

As the data shows, the food reward system in rats seems to organize food intake to precisely match this:

- When the chow is low-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until carb+protein intake is precisely 250 kJ – then they stop eating.

- When the chow is high-carb, the food reward system directs rats to eat until protein intake is precisely 70 kJ – then they stop eating.

I interpret this to show that the food reward system evolved to optimize our health, and in healthy animals does an excellent job of getting us to eat in a way that achieves optimal health.

Note that if the chow is high-carb, rats eat more total calories. Is this because their diet has “high food reward”? No, it is because it is malnourishing. It is protein deficient.

Now, a diet of wheat, sugar, and omega-6 fats is malnourishing. There are any number of nutrients it is deficient in. So the food reward system ought to persuade people to eat more until they have obtained a sufficiency of all important nutrients, and rely on the energy homestasis system to dispose of the excess calories in one way or another. But if the energy homeostasis system fails to achieve this, then obesity may be the result.

If this picture is correct, then what is the solution to obesity? Is it to eat a diet that is bland and low in food reward? I don’t think so; the food reward system evolved to optimize our health. Rather the diet that defeats obesity will be one that is efficiently nourishing and maximally satisfies the food reward system at the minimum possible caloric intake.

A good test of these two strategies is the severely calorie (and nutrient) restricted diet. It would be hard to conceive of a diet lower in food reward than one with no food at all. Yet severe calorie restriction produces temporary weight loss followed by regain – often to even higher weights. This “yo-yo dieting” cycle may be repeated many times. I think this proves that at least some methods of “reducing food reward” – the malnourishing ones – are obesity-inducing.

So I would phrase the goal of an anti-obesity diet as achieving satisfaction of the food reward system, rather than as reducing food reward; and would say that wheat, sugar, and seed oils are obesogenic because they fail to provide genuine food reward, and thus compel the acquisition of additional calories.

Conclusion

Jimmy Moore is friends with the smartest people in the low-carb movement, so this discussion is sure to be interesting. I’m grateful that he’s persuaded people to comment on Shou-Ching’s and my ideas, and I’m eager to hear what Jimmy’s experts have to say.

One thing I’m sure of, the discussion will help us understand the many open issues in low-carb science. It should be a lot of fun!

References

[1] Cordain L et al. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92. http://pmid.us/10702160.

[2] Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D. Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis. Obes Rev. 2005 May;6(2):133-42. http://pmid.us/15836464.

Hi Jean,

I assume you’re not eating an excessive amount of protein. According to this site, http://www.buzzle.com/articles/ammonia-smelling-urine-in-women.html, dehydration and urinary tract infections are the next most common causes; and it’s most common in post-menopausal women.

Paul,

Although my diet is still fairly low carb since I’m just starting to add in more starches, I really don’t get an excessive amount of protein. A pound of ground beef generally lasts me two days. I’m not post-menopausal (late 20’s!) and no urinary tract infection as far as I know.

I have been feeling a bit “dry” lately – both in my skin and my mouth, but I drink 4-6 glasses of water a day.

I’m not sure what to think about this.

Hi Jean,

Didn’t you complain of fungal infections earlier? That’s a risk of very low-carb diets, and fungal UTIs could cause this. The “dryness” in mouth and skin could be a low-carb effect.

I would increase the starches and see if things get better.

Hi Paul,

I don’t have any ‘known’ fungal issues, but I’m sure that is a possibility as I’m certain I have major gut dysbiosis. I have been very low carb for quite some time.

Thanks for the advice. Due to oxalate issues I am avoiding potatoes, so right now I’m focusing only on white rice and will continue to increase that. What I find strange is that the dryness didn’t start until AFTER I began adding some starches. I didn’t have this on the very low carb diet.

Hi Jean,

That’s interesting. Let’s see how things develop with higher starch intake. It sounds like there’s some immune function against something, we’ll have to see if the starches make it worse or better, that will be a clue. The activity could be curative with immunity benefiting from the starch, or reflect a dysbiosis that is feeding on the starch. Time will make it clear. But do drink more water and eat more salt.

Paul,

Somewhere recently you mentioned a tooth infection causing high A1c. Do you think a fungal infection could do the same?

Ellen / Paul,

I’d be very interested in hearing more about how a tooth infection causes high A1c since I do, in fact have an infected tooth!

Jean

Hi Ellen,

I haven’t heard of that happening but who knows. Bacterial endotoxins in the liver can cause metabolic syndrome, that’s a likely mechanism.

Jean,

You might want to try detox aids for lipid toxins, bentonite clay, charcoal, cholestyramine. They might relieve symptoms.

Hi Paul,

One more symptom I wanted to get your take on is body odor. I’ve noticed that to be much, much worse lately while I’m experiencing this dryness of the skin and mouth. I’ve read that is usually considered to be a sign of detox. Do you agree with that?

It could be. It shows some unusual compounds are being excreted in sweat. But I’m not knowledgeable about body odor. It could be any number of things, including some sort of skin infection.

I recommend the teachings of Dr. Rosedale. Just because the diet of our ancestors included cabs does not mean that such a diet if optimal. There is evidence that insulin spikes in other species reduces longevity. Studies in humans is lacking but I am surprised so many agree with Kurt Harris who eats RICE KRISPIES for breakfast.

Kurt Harris also worships the devil and owns a Porsche. At least one of those is true.

Paul,

If possible, could you expound on why starches are more crucial nutritionally than leafy green vegetables? I like plenty of both, so it’s not an issue, I’m just curious about the science behind it.

Thanks,

Steve

Hi Steve,

I wouldn’t have compared them directly myself. Starches are a source of a macronutrient (glucose), leafy greens of micronutrients. So they are not competitors, but complements.

It may be easier to replace the micronutrients from leafy greens by other foods (and multivitamins), than it is to replace glucose if you got rid of starches. In that sense, one could say that starches may be more important. However, you could also take the view that sugars can be an adequate replacement for starches, despite their fructose content.

Since I like you eat both, it’s more an academic and semantic question than a practical one.

From a comment by Chris which explains safe starches:

“it was Paul’s definition in the Perfect Health Diet: page 102:

the safe starches lack fructose, omega-6 fats, and natural toxins, and provide potassium and other nutrients as well as fiber, they are among the most healthful plant foods, and the best source of glucose calories.

Safe in that they lack the toxins.

The low carb ‘experts’ didn’t understand that and Jimmy did not define the term for them. His introduction also made it plain what he thought – it was all about insulin…not the toxins”

http://carbsanity.blogspot.com/2011/10/warning-this-food-contains-starch.html#comments

Paul

sorry if that was inappropriate. I understand your wish to lay off Jimmy. I put that on Evelyn’s blog and it was trying to introduce some context to the discussion, some more accuracy with a direct quote from the book.

Chris

@ Avarind – superb!

That comment about Dr Harris was the funniest thing I have read for a long time.

Chris, thanks for having my back. Of course I’ll be defining safe starches in my reply but it’s great to have friends helping out!

Thought this might be of interest.

http://www.optimox.com/pics/Iodine/IOD-10/IOD_10.htm

It was while treating a large 320-pound woman with insulin dependent diabetes that we learned a valuable lesson regarding the role of iodine in hormone receptor function. This woman had come in via the emergency room with a very high random blood sugar of 1,380 mg/dl. She was then started on insulin during her hospitalization and was instructed on the use of a home glucometer. She was to use her glucometer two times per day. Two weeks later on her return office visit for a checkup of her insulin dependent diabetes she was informed that during her hospital physical examination she was noted to have FBD. She was recommended to start on 50 mg ofiodine(4 tablets) at that time. One week later she called us requesting to lower the level of insulin due to having problems with hypoglycemia. She was told to continue to drop her insulin levels as long as she was experiencing hypoglycemia and to monitor her blood sugars carefully with her glucometer. Four weeks later during an office visit her glucometer was downloaded to my office computer, which showed her to have an average random blood sugar of 98. I praised the patient for her diligent efforts to control her diet and her good work at keeping her sugars under control with the insulin. She then informed me that she had come off her insulin three weeks earlier and had not been taking any medications to lower her blood sugar. When asked what she felt the big change was, she felt that her diabetes was under better control due to the use of iodine. Two years later and 70 pounds lighter this patient continues to have excellent glucose control on iodine 50 mg per day. We since have done a study of twelve diabetics and in six cases we were able to wean all of these patients off of medications for their diabetes and were able to maintain a hemoglobin A1C of less than 5.8 with the average random blood sugar of less than 100. To this date these patients continue to have excellent control of their Type II diabetes. The range of daily iodine intake was from 50 mg to 100 mg per day. All diabetic patients were able to lower the total amount of medications necessary to control their diabetes. Two of the twelve patients were controlled with the use of iodine plus one medication. Two patients have control of diabetes with iodine plus two medications. One patient had control of her diabetes with three medications plus iodine 50 mg. The one insulin dependent diabetic was able to reduce the intake of Lantus insulin from 98 units to 44 units per day within a period of a few weeks.

Thanks, Ellen, that is fascinating. Iodine can do remarkable things, perhaps.

@John W

“I recommend the teachings of Dr. Rosedale. Just because the diet of our ancestors included cabs does not mean that such a diet if optimal. There is evidence that insulin spikes in other species reduces longevity. Studies in humans is lacking but I am surprised so many agree with Kurt Harris who eats RICE KRISPIES for breakfast.

Yes, I would trust someone who thinks “everyone has diabetes”. And I do NOT eat rice krispies at all now. That is a malicious rumor. I eat RICE CHEX when I’m in a hurry.

But seriously. Many people who read extensively about human nutrition go through a phase where they think it might be plausible that the implications of having hyperglycemia imply that eating glucose is “suboptimal”. Then they do further reading in anthropology and ethnology and glucose and insulin metabolism, and they realize that this idea makes no sense, and there is no good evidence for it in normal humans.

Why some get stuck on this idea for years, I am not sure.

@Paul

“Starches are a source of a macronutrient (glucose), leafy greens of micronutrients. So they are not competitors, but complements.

It may be easier to replace the micronutrients from leafy greens by other foods (and multivitamins), than it is to replace glucose if you got rid of starches. In that sense, one could say that starches may be more important. However, you could also take the view that sugars can be an adequate replacement for starches, despite their fructose content.

Since I like you eat both, it’s more an academic and semantic question than a practical one.”

I agree. I was making the comparison in the context of theoretically having to choose between leafy greens and vitamin laden starchy veggies, which is not a choice we have to make.

Fascinating reading but here and at Jimmy’s blog. Paul’s blog is probably my favorite reading at this point. 🙂 Though I’m still not sure what sort of eating plan might be considered best for someone who has *already* been diagnosed as diabetic, and is trying to optimize their health.

Hi Paul,

I’ve taken your advice and started to add some white rice to all my meals – only about 2 T or so per meal. I’m finding that I get somewhat fatigued after and my skin is also getting very tingly, itching, just a strange bugs crawling on me feeling.

I’m wondering if you’re onto something with the suggestion of possible metabolic syndrome. I remember one of the recent Chris Kresser/Danny Roddy podcasts talking about links between hemochromatosis / glucose intolerance / insulin resistance.

If that is what I’m dealing with here do you have any suggestions on how to proceed? Thanks!

Kurt, thank God you corrected the misperception about Rice Krispies. My faith is restored.

I also eat a small amount of Rice Chex without apparent ill effects for something to crunch on. That’s the one thing I really miss.

What about this sentence:

“So breast milk, I think, gives us a much clearer indication of the optimal human diet than hunter-gatherer diets. It is an evolutionary indicator of the optimal diet, but it is not ethnographic or anthropological”.

What did you mean exactly?

Because milk is an indicator of the growth type, but absolutely not of the adult diet.

If it was so, how could a cow eat grass after having drinked such a fat milk?

Excuse my bad english 😛

Hi Mammafelice,

No, cows need fats and protein and relatively few carbs. It is eating grass that is challenging for them, not milk. They need an extremely complex foregut/rumen system to transform grass into food; milk is pre-packaged food that works for cows even if their digestive tract is not yet operational.

The composition of milk is only slightly altered because of infants’ faster growth.

Well, it is not completely true…

A cow has evolved such a complex digestive system just because evolved eating a high cellulose food like grass. It is true, with his simbiotic microflora at the end cellulose fiber are converted into short chain fatty acids. But the same is true, in a minor way, for us as well. Obviously we are not weed eaters and cannot digest cellulose: but our flora help us to digest fibers and resistant starch, producing SCFA as well.

But you cannot give a cow a different food without trouble! Giving a cow a food composed by triglycerids, caseins and lactose will be harmful! Every mammal, once weaned, does not need necessarily the same % ratio of his mother milk…

A cow anyhow was just an example…

We are not cows 🙂 But as lots of us cannot digest lactose while adults, I think that changes may happen even for the optimal ratio between macronutrients.

I’m really sorry for my language poorness!

Hi Paul, ( and Dr. Harris if you are reading! )

I wanted to ask your opinion on something. If you have pretty much determined you have an issue with a food,(observational, then elimination/reintroduction) which appears to be dose dependant…. would you advise to avoiding that item completely?, or eating it in moderation to the extent it doesnt bring on the problems? I know with wheat almost everyone is the paleosphere says NO..even if you tolerate it. How bout a white potatoe? (red skinned are worse then russet for me). The problems are not digestive at all and not joint aches, but rather muscle aches, migrating muscle pin point pains, and then a “too much caffeine” like reaction with anxiousness, inward trembling, creepy crawly and tingling feelings especially in the legs and face and sometimes a racing heart and palpiatations. Tomatoes(salsa, or sause), peppers and sweet potatoes do not produce this reaction in me. I have been hypothyroid for years (do not know if it is autoimmune)and am concerned that if it is, maybe the potaotoe is aggravating it and causing hyperthyroid attacks. Or… if by eating them in small quantites that don’t cause the reaction, would i be allowing some ongoing “inflammation” to not heal? … Or would this more likely be just a sensitivity to potatoes and as long as i am not eating enough to cause the reaction, it should be “safe” ?

Thanks for your time addressing all these concerns people have.

Shelley

Hi Mamma,

Yes, we can convert some fiber to SCFA. But this can be at most ~10% of energy for us, but ~80% for cows. Different digestive tracts matter!

Macronutrient needs do alter as mammals age, but we can predict how they change based on changes in body composition. The major change is the decrease in the percentage of energy consumed by the brain from ~50% in human infants to ~20% in human adults. This reduces carbohydrate needs.

Hi Jean,

Fatigue and itching are usually signs of immune reaction, not of hyper (or hypo) glycemia.

So it would seem you have some kind of infection or gut dysbiosis that likes the rice and generates an immune/autoimmune, probably to circulating toxins of some kind.

Since so many pathogens can digest starch, your symptoms are not very specific, ie they’re not really diagnosable from this comment.

You can try a stool test to see what pathogens you have and then treat those infections. Or you can experiment with low-starch diets like GAPS for a while and try steps to reshape your gut flora (fermented foods, probiotics, enzymes, etc).

I’m afraid I haven’t looked back at your prior comments to remind myself of other symptoms, so please excuse me if I’ve forgotten other clues. The Q&A thread might be a better place for these, then I won’t lose them.

Hi Shelley,

Good question, this was asked in my Chris Kresser podcast too. The first step is experimentation to see what specifically is causing the problem. You seem to have ruled out nightshades. Is it starch generally (does rice affect you)? Is it all kinds of white potato?

Then you can try and find ingredients. Toxin levels in potatoes rise strongly on exposure to light and warmth – do fresh potatoes in dark, cool storage affect you less than

Ultimately, reshaping gut flora and healing the gut is usually the cure for food sensitivities. Excluding the troublesome food usually helps, but then you want to re-introduce it at some point to see if you’ve succeeded in changing the gut flora.

Thanks Paul,

It’s taken me sevens months to be fairly confident it is the potatoe thats causing the problems, but i will continue to tinker with quantities. I may add rice to the mix and see what happens. I’ve never done much with rice. I would assume though if I can eat whole large sweet potatoes for days in a row with none of this happening, then it is not the startch per se that is causing the trouble. I used to be fairly LC and adding startches back really helped with constipation issues so I would hope i wouldn’t have to forgo the startch.

Have you ever heard of Asyra testing? It is based on physics rather than chemisty and measures resonance or energy imbalances in your body in response to a huge number of substances. Theoretically it is supposed to tell you what systems of your bodies are “stressed”. It then tells you what substances add “stress” to your body, and it is also supposed to test for a number of chronic or acute infections. You can also bring the supplements you take or specific foods you eat and have them tested in relation to your body. Sounds interesting and is only $45 so I’m gonna give it a try. I’m bringing my potatoes!

Paul

I was very happy to see your comments here on the food reward theory, as they kinda matched what I feel about it, only actually thought out and articulated in an intelligent manner! Very cool!

I’ve been thinking also about the theory that reduced reward is the reason for initial weight loss on any given diet, (the theory that paleo. for eg, or vegan food actually taste gross compared to macdonalds – which I don’t agree with, btw) but the Shangri-La diet (which looks at food reward as “learned calorie associations”)might put a different spin on it. On that diet, any new flavours do not raise the weight set point, (he calls them ditto foods) while the body decides if this food is actually safe or not. Once the body is sure that it is safe, and full of calories, than it starts to desire it. Imagine primitive man coming upon a new unfamiliar berry bush. We sample, eat a few, wait to see if we die, try it again, eat more, then start gorging. It’s a safety thing. So the theory is, continuously eating new flavours (the gourmet or French style of dieting) will keep you slim. Eating seasonally is another way of doing this.

With any given diet, esp ones that are relying on a very different set of foods, such as paleo, or vegan, usually the food tastes quite different from your regular grub, even normal dieting will if you order the low fat version with salad instead the regular with fries. First you try new things, then you try to revamp old favourites to suit the new theory, then you settle into some new standbys, and voila! weight plateau. Or gain.

What do you think?

I’ve never actually successfully followed the shangri’la diet, but I do think that the theories in it are more interesting than the way Stephan G. articulates them. I wish that they could be tested as they stand in that book.

Also, on another note

I’ve found your comments about yeast and low carb extremely helpful. I was wondering why I ended up in the hospital with diverticulitis while following the initial GAPS protocol, which was supposed to heal the gut! I also had some racing heart and anxiety, too, cortisol related I think. Anyway, your site is the only one that had anything that made any sense.

One more thing about the food reward theory, I’m quoting from memory, but I think it was G. Taubes in Good Calories, Bad Calories, saying something along the lines of “the researches made the mistake of thinking that when animals ate a lot of a given food it was because it tasted good” (instead of being addictive, say, or non-nutritious, or stimulating of the appetite) And I think the same of fast food. When you have a food addiction, it’s easy to wolf it down, but really, who even tastes it? It takes me 10 min. or less to eat a meal at macdonalds. and that’s when I’m eating slow enough to notice the time.

And this is from Jon Gabriel about emotional obesity. “Emotional obesity, on the other hand, is the actual need to be fat, whether consciously or subconsciously, as an emotional survival strategy. You could, in theory, have no positive association with food at all, and derive no pleasure from the act of eating and still have emotional obesity – because it’s not the food that’s important, it’s the fat.”

This struck a chord with me, because I remember gorging on fast food, and it wasn’t really that pleasant. Not that I ate more than one meal, I’m speaking of the speed of eating. Actually, since I started eating protein regularly and my moods stabilized, I haven’t really eaten this way. But I choose fast foods to it with, and it wasn’t really because they tasted “good”. It’s cause they were so familiar the taste wasn’t distracting, and they are so soft they go down quick, and they have enough of all 3 macronutrients to stabilize a blood sugar crash. For a while, anyway.

oops, maybe you could delete the (he calls them ditto foods) from my comment above, really, they should be non-ditto foods! My proof reading failed me.

@Lark,

i don’t like “food reward”

either.

since i’m also a physicist, i prefer

“negative feedback”

vs.

“positive feedback”

(PHD & archevore/panu are my favorite paleo blogs now, but i wish Dr. Harris wrote more)

regards,

Dr Jaminet,

I just finished reading your post on Jimmy’s blog – thanks for the thoughtful and thorough responses to the various comments.

I have a question: your approach, I think, is basically saying that obesity results from consuming too many calories (that is a simplistic representation of your view, I realize). I think Kurt Harris shares this basic idea, though I guess you both explicate different mechanisms by which people do this. For example, if you are eating non-nutritious foods (the SAD), you have to eat a lot more to get your body the nutrients it needs (like in the rat study you mention above).

However, I remember reading about studies (don’t have exact citations at my fingertips) where people eating restricted calorie diets barely lose weight; and on the other side, there are overfeeding studies where people have consumed up to 10,000 calories a day and barely gained any weight (E.A. Simms; Bouchard, I think are the authors of at least 2 such studies). Assuming these studies are legitimate, can you shed some light on this phenomenon?

thanks

Just wanted to say yum to rice chex! That and the new gluten free rice crisps are good snacks if you are in a hurry.

Emily, do you like a special brand of rice crisps?

Dear Dr. Jaminet,

I really love your book. Thank you so much for everything. I have, however, a small question.

I find that I don’t digest rice very well. I think I digest bananas much better. Bananas also contain resistant starch, which increases butyrate in the gut. Can I replace the rice/potatoes etc. with bananas? I am still a little concerned about the fructose in bananas though. Does refrigerating bananas decrease the fructose content?

Thank you so very much.

Chris

Hi Chris,

Bananas are a fine food. They are 2/3 glucose so are functionally similar to sweet potatoes. Plantains may be another option for you, they have less fructose than bananas.

Refrigeration stops the banana from ripening further but won’t destroy fructose that is already there.

Best, Paul

Dear Dr. Jaminet,

I am digesting rice better now, but I have to eat it on an empty stomach. Thank you for maintaining your website.

I also would like to get your opinion on this article.

http://raypeat.com/articles/articles/glycemia.shtml

Peat actually argues that fructose can be a good thing.

Thoughts?

Thank you in advance!

Chris

Hi Chris,

My two most recent blog posts were on Peat’s ideas:

http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=5498

http://perfecthealthdiet.com/?p=5528

Best, Paul

About the breast milk argument; half the carbohydrate in milk is galactose; this is necessary for the growing brain but is relatively toxic to adults – it is more toxic than fructose by some orders of magnitude. Also, in a growing child there is some point to stimulating IGF by keeping insulin elevated.

J Neurosci Res. 2006 Aug 15;84(3):647-54.

Chronic systemic D-galactose exposure induces memory loss, neurodegeneration, and oxidative damage in mice: protective effects of R-alpha-lipoic acid.

Cui X, Zuo P, Zhang Q, Li X, Hu Y, Long J, Packer L, Liu J.

Source

Institute of Gerontology and Geriatrics, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

Abstract

Chronic systemic exposure of mice, rats, and Drosophila to D-galactose causes the acceleration of senescence and has been used as an aging model. The underlying mechanism is yet unclear. To investigate the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in this model, we studied cognitive function, hippocampal neuronal apoptosis and neurogenesis, and peripheral oxidative stress biomarkers, and also the protective effects of the antioxidant R-alpha-lipoic acid. Chronic systemic exposure of D-galactose (100 mg/kg, s.c., 7 weeks) to mice induced a spatial memory deficit, an increase in cell karyopyknosis, apoptosis and caspase-3 protein levels in hippocampal neurons, a decrease in the number of new neurons in the subgranular zone in the dentate gyrus, a reduction of migration of neural progenitor cells, and an increase in death of newly formed neurons in granular cell layer. The D-galactose exposure also induced an increase in peripheral oxidative stress, including an increase in malondialdehyde, a decrease in total anti-oxidative capabilities (T-AOC), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activities. A concomitant treatment with lipoic acid ameliorated cognitive dysfunction and neurodegeneration in the hippocampus, and also reduced peripheral oxidative damage by decreasing malondialdehyde and increasing T-AOC and T-SOD, without an effect on GSH-Px. These findings suggest that chronic D-galactose exposure induces neurodegeneration by enhancing caspase-mediated apoptosis and inhibiting neurogenesis and neuron migration, as well as increasing oxidative damage. In addition, D-galactose-induced toxicity in mice is a useful model for studying the mechanisms of neurodegeneration and neuroprotective drugs and agents.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16710848

also this is very interesting.

http://www.health-science-spirit.com/HF4-1.html

I think he is onto something, and wonder why it isn’t being better researched.

Most European adults and older children who can digest lactose are unable to use galactose efficiently. Babies need galactose as an important building component of the brain, the central nervous system and of many proteins. Thus mother’s milk is even higher in lactose than animal milk to ensure the baby does obtain sufficient galactose.

In later life, very little galactose is needed and this can easily be synthesized from other sugars. Therefore, most of the ingested galactose is converted in the liver to glucose and used as body fuel, but the amount that can be converted is rather limited, even in a healthy liver.

This conversion is a slow and complex process requiring four different enzymes. One of these is sometimes missing from birth, giving rise to a condition known as galactosaemia. Continued milk-feeding leads to a build-up of galactose in the baby and causes cataracts, cirrhosis of the liver and spleen and mental retardation.

If the liver is not healthy, it becomes less able to convert galactose. This fact is sometimes used as a criterion for a clinical liver-function test. If galactose is injected into someone with a defective liver, most of the galactose will later appear in the urine.

MUCIC ACID

Unfortunately, under normal conditions only part of the galactose is expelled with the urine. If there is a deficiency of protective antioxidants, then the rest is mainly oxidized to galactaric acid, commonly known as mucic acid. The great health danger of mucic acid is that it is insoluble. The body cannot let it pile up in vital areas and block organ functions or blood circulation. Therefore, it forms the mucic acid into a sticky suspension in water, called mucus. Thus mucic acid is a main component of pathogenic (disease-producing) mucus

this part has it in more detail:

http://www.health-science-spirit.com/cold.htm

Walter Last is probably wrong about a lot of things, but if so I can forgive him for providing me with this one valuable insight.

Hi

I really like your idea of using human breast milk to estimate the idea carb to fat ratio.

I think you said elsewhere that

“The Perfect Health Diet proportions are more like 300 calories protein / 1300 calories fat / 400 calories carbohydrate”

But human breast milk is (per 100ml) :

carbohydrate (sugar) 7.5g 16.5 kj/g 123.75 kj 44.3%

fat 4.2g 37 kj/g 155.4 kj 55.7%

protein 1.1g 17 kj/g 18.7 kj 6.7%

279.15 kj

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_breast_milk

These seem completely different ratios, from the perfect health diet.

And I would have thought that since babies need to do a tremendous amount of growing, they would require more cell building fat and protein,

compared to the average fully grown adult.

I don’t really understand this.

Regards

John

Hi John,

Human breast milk is 39% carbs 7% protein 54% fat by calories.

But the infant brain is much larger as a fraction of energy usage than the adult brain – >50% vs 20%. So glucose needs are substantially higher in infants.

I would translate that to 20-30% carbs in adults. 20% on a 2000 calorie reference diet is 400 calories.