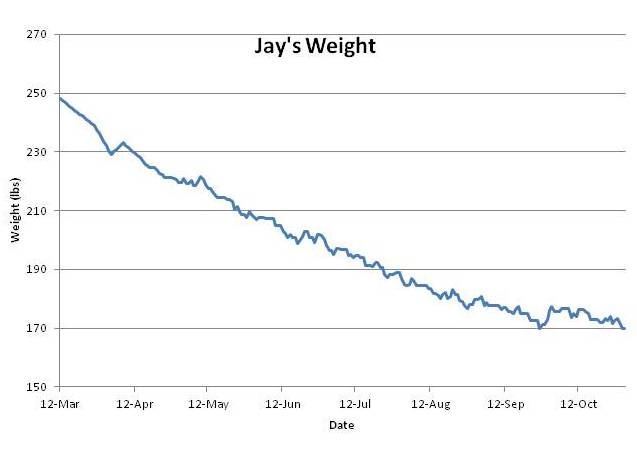

Jay Wright, who comments as “Jaybird,” has had a remarkably successful weight loss story. He adopted our diet in March at a weight of 250 pounds, and reached his normal weight of 170 pounds at Halloween, seven and a half months later.

I met Jay at Wise Traditions in November and can attest that he is now a handsome, slender man.

Jay’s weight loss was remarkably consistent at about 2.5 pounds per week. He agreed to describe his weight loss journey in a guest post; my questions are in italic, Jay wrote everything else. Welcome, Jay! – Paul

I would like to thank Dr. Paul Jaminet and Dr. Shou-Ching Jaminet for writing a great diet book and website! You have been instrumental in helping me achieve the long elusive goal of great health and weight. For me, this truly is the Perfect Health Diet!

Before PHD

Paul: Jay, what do you think caused your overweight condition in the first place?

1. Ignorance and confusion. I believe I would have eaten the PHD way and remained at a healthy weight if I was taught to eat this way from the beginning. Instead, the government promotes the anti-saturated fat, pro-seed “vegetable” oil, and whole grains food pyramid. The belief formed from trusting the experts is a lot to overcome. I remember a decade ago during the Atkins’ hype that I thought that he must be crazy to recommend such a dangerous diet that would go against the “entire” medical establishment. Then, even after I stopped believing the Lipid Hypothesis, I was still confused by all of the rest of the diet claims out there. While I was uncertain, I thought I might as well enjoy a “normal” diet until I can figure it all out.

2. Eating Habits. Besides the high carbs, food toxins, and malnourishment of the food pyramid diet, a few other factors may have affected my eating habits. I was a normal weight child growing up and I could eat anything and everything in sight and not get even pudgy in the slightest. When all foods have the same effect – none – you don’t worry about whether the food is healthy. Also, I spent my childhood playing one sport after another which might have actually worsened my eating habits. At least here with Texas football, we were constantly encouraged to stuff ourselves and put on more weight. When sports ended for me after college, normal amounts of food looked like a starvation diet on a plate!

3. Carelessness toward health. Was I careless because I was told “healthy” meant a yucky salad and “unhealthy” meant a yummy steak? A young boy always chooses the steak especially when I was constantly hungry from 3 hour practices! This all started to change after my dad was diagnosed with heart disease and started eating a “healthy” low-fat diet. However, the real wake-up call came when my mother was diagnosed and eventually died of breast cancer! To fight the cancer, she put up a courageous fight by being the most dedicated eater of an “alkalizing” vegetarian diet ever! Yet, even though I began to care more about health, I continued to allow myself to eat anything while I learned more and took breaks from trying different diets.

4. Lack of exercise because of a bad back. I have had a herniated disc in my lower back for about 10 years now. When I changed careers and became even more sedentary, my back problem only worsened from bad posture while sitting. I should have at least continued to walk short amounts, but at the end of the day, I didn’t even feel like tolerating even a little pain after dealing with it so much during the day. The recliner offered relief.

5. Convenience. As a single guy, I relied on eating out for convenience over the years and pre-made frozen dinners when I ate at home mostly. Starting a diet always meant making big changes to my routine and giving up a lot of time to cook.

6. Diets were Too Low in Food Reward. Looking back, all the diets I tried were much lower in food reward than the “regular” American diet with lots of sweets that kept calling to me! All of the previous diets required a Herculean will power just to fight the temptations. It was mental torture being on a diet!

Paul: Jay, what were your experiences on the various diets you tried – and what caused you to give them up?

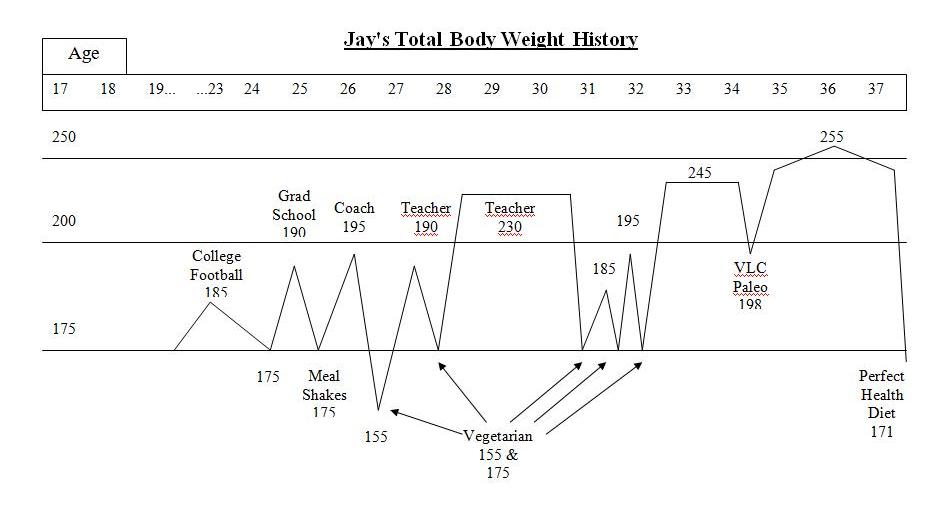

Here is my weight history:

After college sports, I struggled with my weight. I was a yo-yo dieter – I could lose weight but it always ended up even higher. I tried meal shake replacements, frozen dinners to limit calories, no meat/meat, no dairy/dairy, acid/alkaline, exercise/no exercise while dieting, no cash or credit cards in my wallet going to work so I wouldn’t stop at a fast food, punishment where I had to eat a raw tomato if I cheat (I hate raw tomatoes), and many other vegetarian leaning and mental tricks. A pattern emerged with these diets. I would starve with low energy for about a week or two until my will power ran out. Then, I would go eat something “bad.” If I continued to repeat the pattern and managed to be “successful,” I stayed hungry even once I reached my goal weight. I tried to transition to a “regular” amount of food to stop starving and just maintain but to no avail. My weight went right back up even higher than before even without cheating on the diets.

Paleo was finally the exception to the starving rule, but only at first. I felt great on a very low carb paleo for a couple of months. I ate a pound of meat a day and mostly vegetables with a little fruit and nuts and a lot of coconut oil. The extra fat and meat seemed to enable me to lose weight and not be hungry. I lost nearly 40 lbs and halfway to my goal. However, I started to not feel so well and hunger was returning, too. I had headaches and energy fluctuated throughout the day. I never liked the taste of vegetables and I began dreading the need to eat more vegetables than I had ever cared to eat in my life. Also, the sugar cravings never stopped just like on the vegetarian diets. Eventually, will power ran out eventually on paleo just like on the other diets.

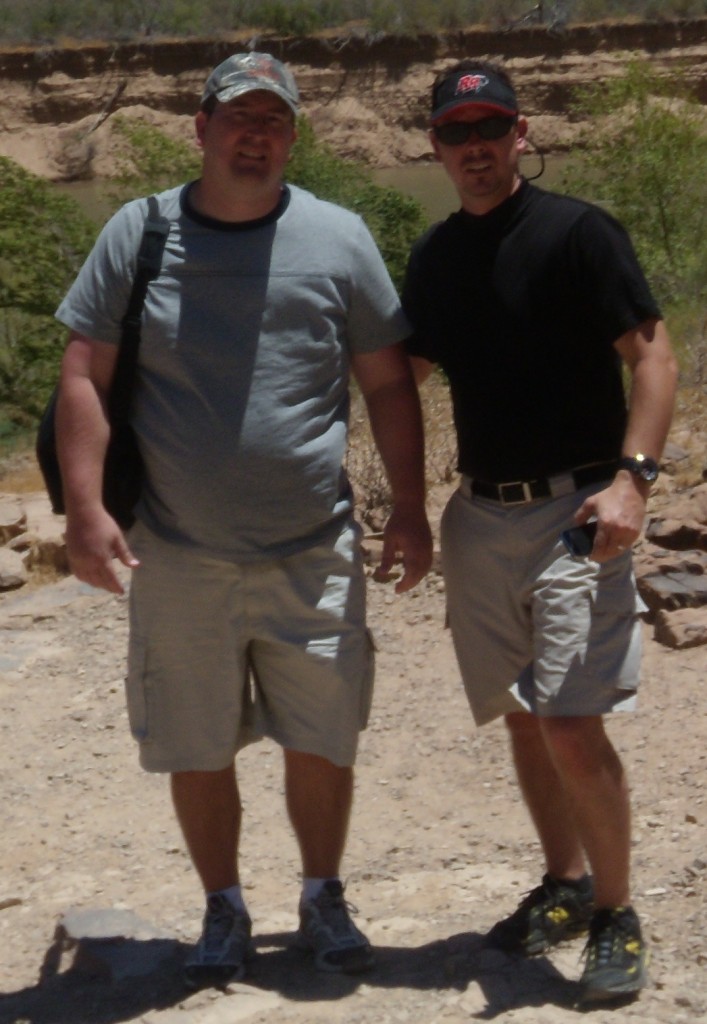

Here’s what I looked like at 250 pounds. I’m the one on the left in the gray shirt; the one on the right is my brother Craig Wright:

I knew I had better find an answer when my family and friends would laugh each time I declared, “Diet starts tomorrow!”

Paul: Jay, it’s very interesting that on pre-Paleo diets you were always hungry, and when you ate to satisfy your hunger, your weight returned to as high or higher than when you began. That’s consistent with the set-point theory of obesity: your set-point hadn’t changed, and so when you reduced weight below the set-point, you got hungry; when you ate to satisfy your appetite, you were obese. The Paleo experience could also be said to be consistent with the set-point theory: it reduced the set-point so you lost 40 pounds without hunger, but weight was still above normal and hunger returned as your weight got below the new set-point.

An interesting data point, which I see as a challenge for the setpoint theory because it suggests an alternative view, is that on VLC Paleo your hunger returned at the same time you began to feel unwell. This suggests that hunger and setpoint are really an index of health, and when the body is not being properly maintained the brain manufactures hunger. When nutrients are abundant and the body has all it needs to establish good health, the setpoint is reduced to normal weight, hunger disappears, and weight loss resumes.

Perfect Health Diet

Paul: Jay, what was your experience on PHD? I’m especially interested in whether you experienced plateaus where weight loss stalled, and whether you experienced hunger as on other diets.

I recorded my weight every day from April 15 through November, and enough days in March and early April to give a clear picture. Here is what happened:

As you can see, there was no stall in weight loss until I hit my target weight of 170 pounds.

Here’s my after photo, again with my brother Craig. This time Craig is on the left in black, I’m on the right in green:

Interestingly Craig has eaten pretty much the same foods as I have throughout life, and always maintained a normal weight. On my recommendation he adopted PHD soon after I did, and he also experienced health improvements – psoriasis, which he’s had for 20 years and used to leave red scales over much of his body, is nearly gone.

Hunger

I followed the PHD weight loss protocols and felt virtually no hunger throughout the 7 months. Intermittent fasting with one meal a day worked best for my schedule; I coconut oil fasted earlier in the day and 1 day per week. After the first month, I coconut oil fasted for an entire week since I figured I should clean out my system. Then I dropped the calories to only 1200 to get some faster results early on to help my back. I thought I would readjust the calories up or the eating schedule according to my hunger, but I did not experience any hunger and had great energy so I left the plan alone. What little hunger I did experience was very mild and just meant it was time to drink another bottle of water or swig a tablespoon of coconut oil before the evening dinner. Interestingly, I ate some birthday cakes toward the end and experienced stronger and more uncomfortable hunger the following days than the previous months. The lack of hunger was definitely a key to my weight loss success.

Food Reward

For me, PHD is a high food reward diet. It tastes great every meal! Even in the beginning of the diet, I enjoyed the PHD meal just as much mentally as thinking about eating my old food. Later, my taste buds changed and PHD became clearly the more rewarding food. However, at least part of the PHD was bland. The coconut oil provided calories with no taste and helped keep my calories low. Yet, I really believe I would not have lasted on the diet if the food was bland. Having a neutral taste reminds me of the very low carb paleo diet that didn’t allow the safe starches and even small amounts of dairy. The white rice and white potatoes enabled me to eat vegetables regularly by buffering the taste until my taste buds adjusted and I began to like them. Avoiding milk but having small amounts of other dairy also went a long way in the enjoyment of the food and menu options. The safe starches, dairy, and a little bit of fruit also seem to be responsible for satisfying my sweet tooth cravings. I’m not sure if the high food reward PHD would have controlled my calorie intake since I counted calories. Nonetheless, compared to the other past diets I dreaded to eat, I prefer the high food reward of PHD. I use to say, “Why does all of the food that’s good for you taste so bad and all of the food that’s bad for you taste so good?” I don’t say that anymore with PHD.

Plateau

My belief is that total calories do matter. I’ve always been able to lose the fat and get back to my original weight provided that I lower my calories enough to accomplish it. However, my will power usually ran out before I accomplished it many times. The constant hunger and low energy with lower calories exhausted my desire to lose the weight on previous diets. In contrast, I experienced the opposite on PHD. While the PHD food and supplements provided satiety and energy, I controlled my calories by exercising, counting calories, eating only a single meal, and having oil fast days. Even after only a month, I experienced such a surge in energy even on lower calories that I increased my exercise to 2 hours of walking. Having established such a low calorie amount in the beginning with a challenging exercise and eating plan, I simply had to maintain the routine until the goal was reached.

I believe the key was PHD enabled me to maintain low enough calories to not experience a plateau as on other diets.

Set Point

My experience might show some truth to the concept of a set point. For instance, prior to starting PHD my weight stayed consistently within a 5 lb range for about 2 years. During this period I was eating whatever I wanted. My experience on PHD could be construed as the resetting of my set point to my normal weight – 170 lb. I was never hungry on PHD as long as my weight was above 175 lb. I started feeling more hunger once I got close to my normal weight in the 170s. Unlike previous diets, I was able to eliminate the hunger by eating a little bit more — just upping my calories slightly.

Although other diets could get me to this weight point before, I had to stay in a perpetual starving mode to remain at this level. Unlike on PHD, on other diets adding enough calories to stop hunger always led to a rebound of weight that leveled out at a higher level than before I started.

When I started PHD my intended target weight was 175 pounds. With PHD, I actually continued to lose a little more than the 175 down to 170 without planning on it. Then, my weight slightly increased with obvious cheats like some birthday cake. While eating the normal amount the following days without the cheats, the weight returned to previous levels without an effort to compensate. After the weight loss, my weight has become more stable. The last month I have had several repeating days on the weight scale with the same exact weight number to the tenth of a point. This occurred even though I ate more on a few of the previous days. My weight history shows a stair stepping up higher with each diet attempt until PHD stabilized my weight back to its original healthy level.

Closing Thought

During the middle of my weight loss, I was at a restaurant eating a salad with balsamic vinegar and olive oil dressing, 8 oz steak, and a baked potato with butter and sour cream and some water with lemon, but without a dinner roll. I paused and proclaimed, “I can’t believe I’m eating this and still losing weight! This is the BEST DIET EVER!”

Recent Comments